Emerson Howard, Kaira Edwards, Kat Balchunas, Kylee Bourbon, Nicole Hernandez

“Ok storytime.” “Get ready with me to go to class.” “Doing my makeup for literally no reason.” We can’t get enough.

Why are “get ready with me” videos so captivating? Are the communicative methods used what contributes to flop or fame…. a like or dislike…a slay or a nay?

In recent years, a new wave of social media “influencing” has emerged. The phenomenon of self-branding, the continuous action of establishing an image or identity of oneself, is most relevant in such an industry. We sought to investigate how influencers’ slang and body language used in “Get Ready With Me (GRWM)” videos conveys or does not convey a sense of perceived authenticity from followers. Our study focuses on three popular lifestyle influencers and their GRWM videos on the platform TikTok. We sought to identify patterns of body language, speech, and audience perception within GRWM videos that allow our subjects to establish and maintain an authentic relationship with their audiences. We hypothesized the intimate and casual nature of GRWM videos allow creators to establish a more personal connection with their audience if accompanied by a positive tone of voice, use of inside slang, as well as high levels of engagement.

Introduction and Background

TikTok is a rapidly growing social media platform which revolves around the creation and sharing of short, user-generated videos (Montag et. al, 2021). The app launched in 2016 and since then has provided an outlet for social media influencers, who are users that obtain a large following through posts, engagement, and advertising (Abidin, 2015). Our study looks specifically at white, female lifestyle influencers aged 18-30 who are recognized for documenting seemingly inconsequential and mundane elements of everyday life such as putting on makeup, getting dressed, etc. These influencers communicate personal information about themselves to create a sense of intimacy between them and their followers, emphasizing their realness and relatability (Abidin, 2015). Like any other social media influencer, lifestyle influencers create a “brand” for themselves by developing a consistent theme and style for their account through patterns of language, images, and content in order to create a certain expectation for how people should perceive them (Marshall).

To provide a basis for our understanding of how TikTok influencers create a ‘brand’ for themselves, we apply Erving Goffman’s dramaturgical approach to the digital media space to explain how influencers put on a performance through self-branding. Goffman’s dramaturgical theory proposes that everyday interactions are like a play in which humans put on a performance. This phenomenon is often displayed on social media in which influencers curate their posts and profiles to express an idealized presentation of self. Influencers employ impression management by being selective with what to post publicly, in order to preserve the identity they have curated for themselves—their “brand.” We feel that GRWM videos uniquely blur the line between Goffman’s concepts of backstage and frontstage, since these videos are predicated on providing followers with a sense of intimacy, seeing the ‘backstage’ of an influencer’s daily life. These videos commodify intimacy by providing the audience with the impression they are privy to intimate and generally inaccessible aspects of the influencer’s lives—this is what makes lifestyle influencer branding successful (Abidin, 2015).

Methods

For our data, we gathered and analyzed the three most recent “GRWM” videos from February 17th to March 1st, from the selected lifestyle influencers: Alix Earle, Darcy McQueeny, and Mikyla Nogueira, to investigate how they create a persona through language and behavior patterns. We gathered our data via the TikTok social media platform and the data was collected in two separate categories: video content and audience response. To observe video content, we looked at their patterns of communication including their body language, as well as their use of “inside slang.” We then observed audience response by focusing on the top seven comments to investigate whether there was a more positive or negative reception, as well as the number of likes per comment. This allowed us to measure each influencer’s level of audience engagement, level of influencer engagement, and engagement sentiment. We then took into account any differences and similarities that may exist amongst the influencers and how those aspects account for the way they’re perceived.

Results and Analysis

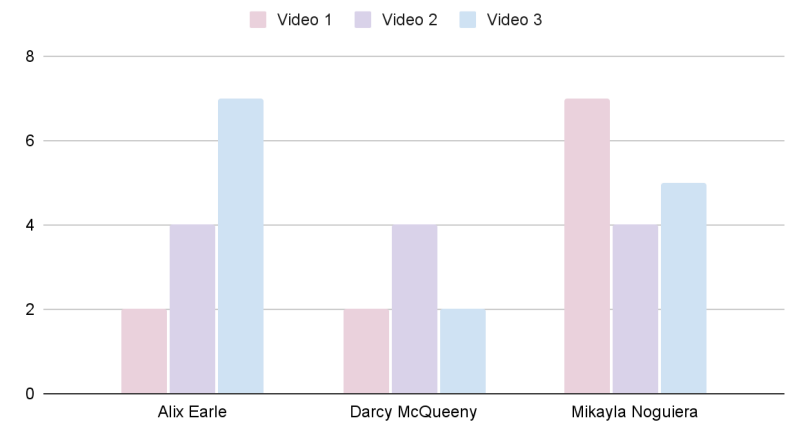

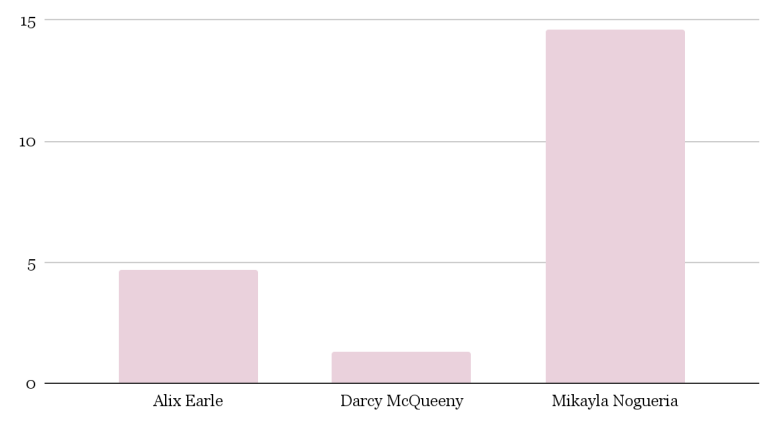

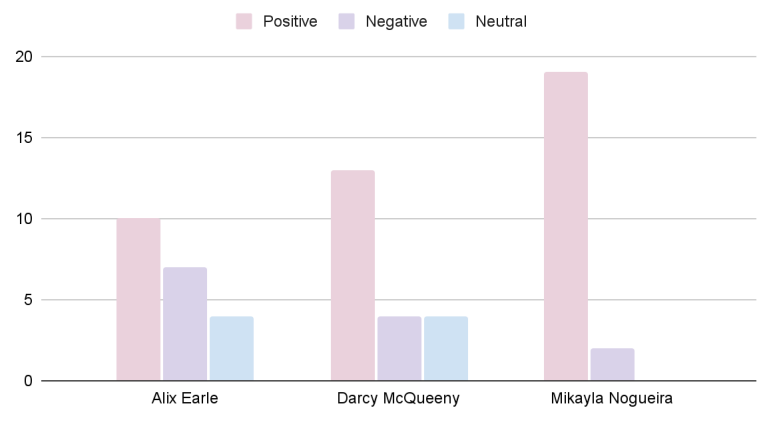

Our research both confirmed and rejected aspects of our hypothesis that GRWM videos allow creators to establish a more personal connection with their audience if accompanied by a positive tone of voice, use of inside slang, as well as high levels of engagement. After measuring the creator response rates within their comment sections, we noticed that Mikayla Nogueira had the highest level of engagement with viewers (see Figure 6).

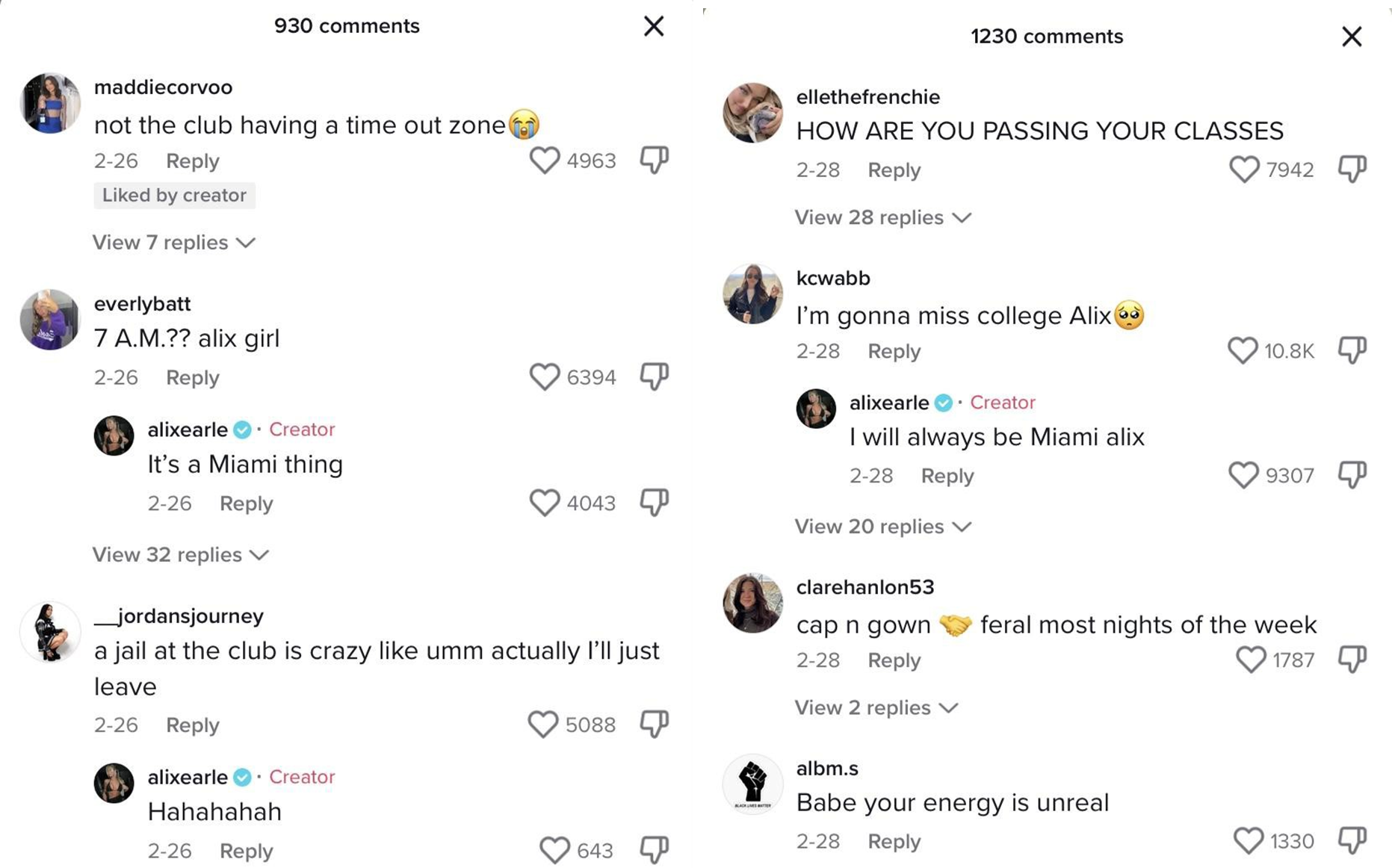

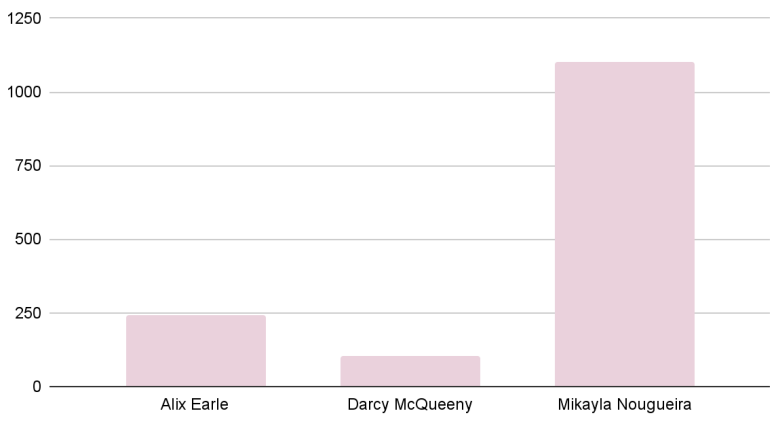

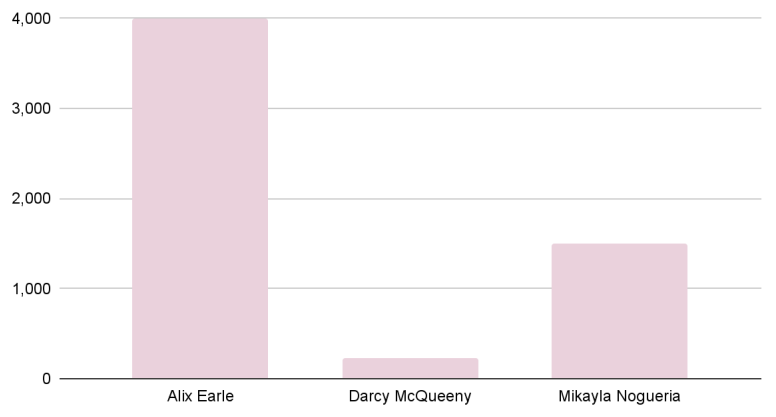

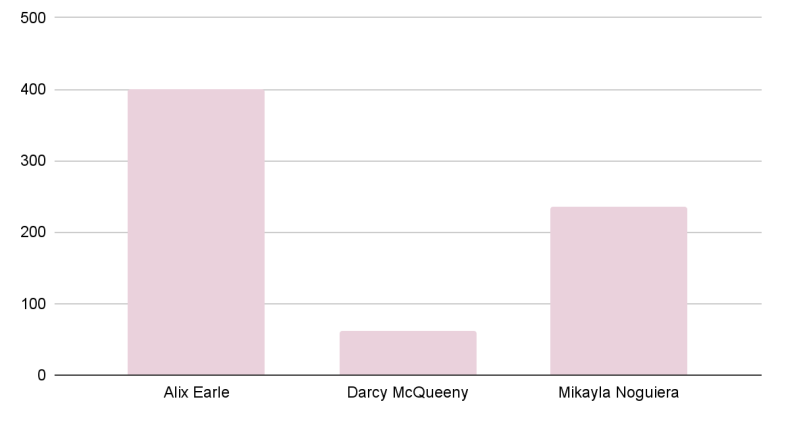

She not only responded to comments more frequently than other creators but also in a variety of ways: liking, messaging, and video responding. However, Alix appeared to have more audience engagement (see Figures 3 and 5) of all influencers we investigated despite her not interacting with them as much as Mikayla.

Despite having greater creator engagement, followers (see Figures 1 and 2) and the most positive engagement sentiments (see Figure 4), Mikayla Nogueira received less likes per GRWM video (see Figure 5) and likes on the top 7 comments (see Figure 3) per GRWM video (236.4k / 1,506), than Alix Earle (400.9k / 3,996). Darcy McQueeny received the least likes per video and comments (61.8k / 227).

Through our analysis of this data we established that, as opposed to our hypothesis, it is a “laid-back” neutral tone of voice, use of inside slang, and moderate levels of engagement that is most popular within GRWM videos and most effective in garnering audience engagement.

We observed that Alix is a very good storyteller, creating a more laid-back demeanor and anecdotal style of GRWM videos that is more relatable amongst audiences. Mikayla can seem too enthusiastic, as if she is trying too hard to be liked and seen as a positive person (i.e. “Thank you!!! [exuding love face emoji]”); while Alix interacts just like a friend would on Facetime and responds to comments similar to how friends respond to texts; in a more neutral and moderate manner (i.e. “Hahahahah,” “No”). Mikayla expresses herself very openly and her outgoing personality may be a bit overwhelming for some. Additionally, her high level of engagement with her comment section may appear to some as trying too hard. Contrastingly, Alix exudes a more relaxed persona, talking about her friends as if the audience knows them personally, to solidify this ‘friend-like’ relationship, and utilizing slang such as “it’s not giving” throughout various videos and “losers,” which she notes is used by her own friend group, allowing the audience to feel included. We found that Darcy McQueeny utilizes a monotone/unengaging tone of voice and scarcely engages with comments, resulting in her low levels of likes, audience engagement, and negative engagement sentiments.

Discussion and Conclusions

In relevance to class, this course is centered around social communication and how our everyday speech and interactions are revealing of identity and character. We are able to better understand tone in internet gestures the more we partake in them. Additionally, verbal variation, in that influencers are distinguished on TikTok by speech variation. We also suspect that the successful influencers don’t switch from their normal and internet personality. If we had more time, we would be interested in conducting more research about this.

With self-branding on social media having an ever-growing prominence in modern social communication, especially among our age group, we thought this topic was relevant and crucial to study. Now when we navigate our social media presence, we are keener on how the language and the level of formality we use affects those viewing us.

The limitations in our research included the use of interpretive/qualitative data, restricted data (3 videos, 3 creators), and a narrow demographic (young, white, girls).

References

Abidin, C., (2015). Communicative Intimacies: Influencers and Perceived Interconnectedness. Ada: A Journal of Gender, New Media, & Technology, 8, 1-16: http://adanewmedia.org/2015/11/issue8-abidin/

BBC Radio 4. (2015, April 15). Erving Goffman and the Performed Self [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/6Z0XS-QLDWM

Goffman, E. (1959). The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

Hogan, B. (2010). The Presentation of Self in the Age of Social Media: Distinguishing Performances and Exhibitions Online. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society, 30(6), 377–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0270467610385893

Jennings, R. (2018). What Is TikTok? The App That Used to Be Musical.ly, Explained. Vox, www.vox.com/culture/2018/12/10/18129126/tiktok-app-musically-meme-cringe.

Marshall, S. (n.d.). An introduction to brand building through social media – learn. Canva. https://www.canva.com/learn/introduction-brand-building-social-media/

Montag, C., Yang, H., & Elhai, J. D. (2021). On the psychology of TikTok use: A first glimpse from empirical findings. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.641673

Pulse Advertising. (2021, September 1). What Is an Influencer? | Influencer Marketing Explained [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/JLiKXW82tjE

TikTok Videos

- Alix Earle

- Darcy McQueeny

- Mikayla Nogueira