Tess Ebrami-Homayun, Saba Kalepari, Hannah Pezeschki, Shaina Tavari

One in five parents reports that they will never have a conversation regarding sex education with their children. The avoidance and uncomfortable nature of this conversation led us to explore the differences in communicative patterns between mothers and fathers to find what gives this conversation these attributes. To conduct our research as UCLA undergraduate students, we analyzed various media portrayals coming from advertisements, movies, and TV shows. We looked at how often euphemisms and communication aspects occur. In our research, we were able to find distinct patterns in every “talk,” such as low tones/long pauses, similar settings, conversation ending on a ‘high,’ indirectness/vague word choice, awkwardness/shame, and lack of eye contact. By bringing attention to these patterns, we can provide parents with a better understanding of how to communicate sexual health concerns to their children.

Introduction and Background

“The talk” refers to the first and awkward time when a parent(s) explicitly discusses sex and sexual health with their children, often showing typology themes of awkwardness and seriousness that are attributed to “the talk.” This conversation has an uncomfortable and awkward connotation attached to it, leading us to want to explore the linguistic and communicative patterns that collectively work together to give “the talk” this connotation (Ashcraft, 2017). In our study, we found a difference in the way parents speak to their children about sexual health depending on the child’s gender. This TED talk highlights the importance of having “the talk” to combat the negative association with the subject of sex (Talking dirty: De-stigmatising conversations on sex | Kate Dawson | TEDxGalway). Our target population is various types of media portrayals within the last 20 years of “the talk” between parents and children between the ages of 13-20. Our study attempted to answer the research question of how different communication aspects between mothers and fathers culminate in the shameful nature of “the talk.” We predicted that our research would show different communicative patterns between mothers and fathers (Grossman, 2022). Furthermore, we discovered common communicative patterns in “the talk” between mothers and fathers, such as low tones/long pauses, similar settings, resolution, awkward body language, and indirectness, including vague word choice.

Methods

The methodological design we used to collect data for our research on “the talk” was looking at available digital media examples depicting “the talk” between a parent and their child, specifically scenes from TV shows, YouTube videos, or ads using stereotypical patterns associated with “the talk.” Every member of the group had a similar idea of what to look out for in the data samples: awkwardness, similar settings, conversations about sex specifically and not puberty, long pauses, lack of eye contact, indirectness or vague word choice, and a resolution at the end of the conversation. We collected seven media portrayals from advertisements and scenes from movies and TV shows, to see how often euphemisms and communication aspects occur.

Results and Analysis

From our data results, we discovered that “mothers display similar levels of concern toward sons and daughters” about “the talk,” while fathers exclusively spoke to their sons about the talk (Butler, 2008). These results reflect similar gender stereotypes regarding the mother’s and father’s roles in the household, where the father is the ‘breadwinner,’ and the mother is the ‘homemaker’ (Robles, 2017). Mothers are often expected to take on extra household tasks, including having “the talk,” without any additional credit. Contrastingly, fathers simply have to go to work to provide income for the household, receiving praise for being the ‘king of the house.’

Notably, our results should not be taken as true results of an experiment since we did not conduct inferential statistics. In the 7 data samples we coded, the results showed low tones/long pauses, similar settings, conversation ending on a ‘high’, indirectness/vague word choice, awkwardness/shame, and lack of eye contact.

Low tones and long pauses

Low tones and long pauses were specifically prevalent in the mothers giving “the talk,” while fathers were more abrupt and aggressive in their tone of voice. This difference can show the natural softness present in mothers as opposed to fathers generally being more abrasive in their speech (Darling & Hicks, 1982). For example, in the TV show Young Sheldon, the father is giving “the talk” to his son, but his tone of voice suggests his disinterest (Figure 1):

“I’m just gonna grab a beer.”- Dad

“Has he had the talk yet?”- Grandma asked Sheldon’s Father

“Cmon’ Connie”- Dad rolling his eyes at the grandmother

“You’re probably not going to [have sex]”- Dad to his son Sheldon

In Young Sheldon, the father is seen completely brushing off the conversation and discouraging his son from having “the talk.” In contrast, what we found in the mothers in our data sample; for example, in Big Mouth, frequently talk in a low tone to support their daughter, who claimed to have had a bad sex experience and no longer wants to have sex. The mothers in our data were much more willing to have “the talk,” using softer tones to suggest supportiveness and understanding of the uncomfortable conversation.

Settings

There were also similar settings in all the data samples; nearly every scene was on a bed or couch, with the parent and child sitting on opposite ends. The lighting in our data was mostly dim, probably to depict a sense of uncomfortableness for the subjects in the data. The settings were consistent between mothers and fathers when having “the talk” with their children. For example, in Sex Education, Otis is having “the talk” with his mother in their living room on the couch (Figure 2):

“Do you want to talk about it?- Mom

*Otis in silence*

“I want you to know you can talk to me about anything. This is a safe place”- Mom

“This is not a safe place mom, you need to stop analyzing everything I do”- Otis as he storms out of the room

The mother was supportive in this conversation, while Otis was wildly uncomfortable. Part of this could be from the setting of the room, which was dimly lit, and because they are sitting on the couch trying to keep a distance between themselves. If the lighting is dim, the person is likely to feel uncomfortable (Michigan State University, 2018).

Ending on a ‘high’

In our data samples, “the talk” always ended on a ‘high’; there was always a resolution by the end. For example, in the Amazon ad (Figure 3) we sampled, the conversation between the mother and her daughter went like:

“I’m glad we had this talk”- Mom

“Me too”- Daughter

While the conversation is happening, the parents and the child are uncomfortable. However, by the end of “the talk,” there is some sort of resolution to end the conversation and address that the conversation was necessary.

Indirectness and Vague Word Choice

There was also indirectness and vague word choice in all of our data samples. Patterns associated with indirectness included avoiding the word “sex” explicitly and the general topic of sex in the conversation. For example, in our Bridgerton sample, Lady Bridgerton ends the conversation when her daughter asks about sex. (Figure 4):

“How does a lady come to be with child?” – Eloise to her Mother

“What Eloise?”- Mother

“I thought a lady had to be married.”- Eloise

“Eloise that is more than enough!”- Mother

*Eloise’s brothers enter the conversation*

“Don’t look at me”- Brothers

“I do hope the two of you [the brothers] are not encouraging improper topics of conversation”- Mother to Brothers sitting with Eloise

“Not at all Mother”- Brothers

In this conversation analysis the mother shuts down the conversation by avoiding using the word “sex,” and by deeming the conversation in general as ‘unladylike.’ Eloise did not even know what ‘sex’ was, as she thought it was a product of marriage.

Awkwardness and Shame

Awkwardness and shame are heavily associated with “the talk” from our gatherings. We found that themes of awkwardness and shame are present in all seven data samples. One example is from That 70’s Show, where we see the father on numerous occasions responding in an abrupt tone to demonstrate his strict attitude against sex to his son (Figure 5):

“Let’s talk about birth control” – Kitty Forman to her son

“Birth control? Don’t do it. That’s your birth control” – Red Forman responding to Kitty Forman to his son

“Did you know Lori is flunking out of college?” – Eric Forman asking both parents

“Don’t change the subject. You got strange thought in your little head mister and that Don is a nice girl” – Red Forman told his son in response

“Red, you’re giving him the wrong idea about sex. It’s not dirty-” – Kitty Forman in response to Red

“But it’s not clean either” – Red Forman’s response

The father was frequently stern in his approach to clearly show his son that sex is a ‘dirty’ activity he should not partake in. When it came to his son, he was quick to highlight all the reasons he should not do it because it’s shameful. The father inflicts shame on his son for even mentioning sex, while the mother tries to alleviate that shame by deeming “sex” as “not dirty.” Both parents should make their children feel comfortable and build up their self-esteem with “the talk” to normalize it (Keeton, 2019).

Eye Contact

Lastly, we noticed a lack of eye contact during “the talk” until the resolution occurred at the end. Lack of eye contact may be associated with the awkwardness of “the talk,” where neither the parent nor child wants to be there having the conversation. Avoiding eye contact can be a way that humans try to avoid the conversation as a whole (Parvez, 2023). This can be seen in our data sample from Friday Night Lights, where the mother is having “the talk” with her daughter. (Figure 6):

“What about Birth control?”- Mother

“Mom, I don’t want to talk about it.”- Daughter

“That’s the conversation.”- Mother

“Yes, we’re using birth control”- Daughter

In the beginning parts of the conversation, the daughter visibly looks uncomfortable. Not only does her body posture suggest it, but also the lack of eye contact while talking about contraceptive use. This suggests that the mother and daughter are uncomfortable with this topic (Mullis, 2020). While the conversation is obviously awkward between the mother and daughter, the mother still has a low tone of voice while trying to be supportive of the daughter’s decision to start having sex.

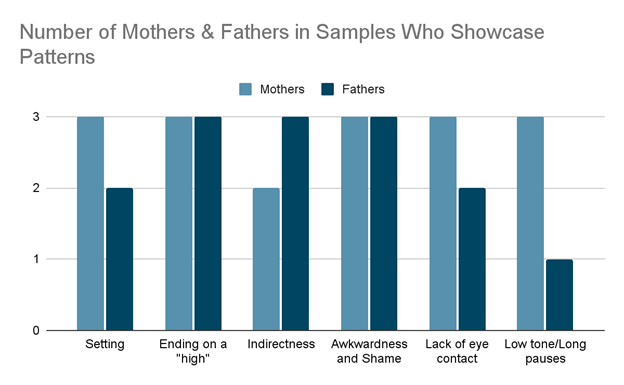

Based on our 7 data samples and the above-mentioned communicative patterns relevant to “the talk” when analyzing the data, we see the gendered differences between mothers and fathers during “the talk.” Figure 8 provides a bar chart depicting how often each communicative pattern in “the talk” that we mention appears with each parent.

Discussion and Conclusions

Having identified the communicative patterns culminating in the uncomfortable nature of this conversation, parents can approach this situation differently in efforts to create a more welcoming and comfortable environment for them and their child. The samples show common themes within “the talk” in regard to communicative patterns between mothers and fathers. While our data samples supported our predictions, it is important to note that we did not conduct a true experiment or present inferential statistics. Any quotes we used to back up our results are only with the assumption that if we properly conducted an experiment, our results would be generalized to the public, however, we cannot because these are not true scientific results.

A parent’s word choice and level of directness regarding sexual health have the potential to impact their body confidence and safety (Ashcraft, 2017). The data collected shows that by changing or eliminating said behaviors, like maintaining eye contact and avoiding long pauses, parents can work towards fostering a welcoming environment when having this conversation with their children. In our attempt to examine the ways the media portrays “the talk,” we wanted to see how mothers and fathers approach the conversation, and whether it differs when talking to their sons or daughters. While “the talk” is naturally uncomfortable, it is inevitable, so children can have an honest education on sex. Hence, the importance of demonstrating the ways different approaches may foster either a successful or unsuccessful educational experience between a parent and child. By considering the various familial dynamics during “the talk” that could create an awkward and uncomfortable atmosphere, we may emphasize effective tools to help improve the overall outcome of the conversation and strengthen family communication.

1= barely present in the sample

2= moderately present in the sample

3= highly present in the sample)

References

Amazon (2022). “Amazon TV Spot, ‘Savings Talk’.” Amazon. https://www.ispot.tv/ad/bvmb/amazon-savings-talk

Ashcraft, Amie M, and Pamela J Murray. “Talking to Parents About Adolescent Sexuality.” Pediatric clinics of North America vol. 64,2 (2017): 305-320. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2016.11.002

Butler, R., and Shalit-Naggar, R., (2008). “Gender and Patterns of Concerned Responsiveness in Representations of the Mother-Daughter and Mother-Son Relationship.” JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/27563524, pp. 836-851.

Darling, C. A., & Hicks, M. W. (1982). Parental influence on adolescent sexuality: Implications for parents as educators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 11(3), 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01537469

Grossman, J. M., Richer, A. M., Hernandez, B. F., & Markham, C. M. (2022). Moving from Needs Assessment to Intervention: Fathers’ Perspectives on Their Needs and Support for Talk with Teens about Sex. International journal of environmental research and public health, 19(6), 3315. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063315

Herron, K. (2019). Sex Education. Eleven Company, Retrieved from Season 1 Episode 1 on Netflix.

Keeton, G. (2019). Home – focus on the family. The Talk. Retrieved February 16, 2023, from https://www.focusonthefamily.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/The-Talk.pdf

Michigan State University. (2018). Does dim light make us dumber?. ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 22, 2023 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/02/180205134251.htm

Mullis, M. D., Kastrinos, A., Wollney, E., Taylor, G., & Bylund, C. L. (2020). International barriers to parent-child communication about sexual and reproductive health topics: a qualitative systematic review. Sex Education, 21(4), 387–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2020.1807316

Parvez, H. (2023). Avoiding Eye Contact in Body Language (10 Reasons). Psych Mechanics. https://www.psychmechanics.com/avoiding-eye-contact/

Robles, J., and Kurylo, A. (2017). “Let’s Have the Men Clean up’: Interpersonally Communicated Stereotypes as a Resource for Resisting Gender-Role Prescribed Activities.” JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26378342, pp. 673-693.

YouTube. (2021, November 5). Big mouth: The sex talk. YouTube. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Es2DyU755GQ

YouTube. (2020, December 28). Bridgerton – how does a lady come to be with a child. YouTube. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vQyrXWOEzjw

YouTube. (2020, June 19). Georgie getting the talk #youngsheldon. YouTube. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UoBbDkBiep0

YouTube. (2012, December 17). Red Forman and kitty about sex. YouTube. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9DumgFFVPQs

YouTube. (2022, May 2). Tami and Julie have the sex talk | friday night lights. YouTube. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cFtexFWJ0HQ