Yasmine Choroomi

Have you ever heard people use words like “yeah”, “mhmm”, or “right” while you’re speaking to them in a conversation? This method of cooperative communication is called supportive overlap in linguistics and can be presented undetected in mundane conversations. Although such an interaction can take place in less than a second of conversation and is sometimes overlooked, it can be used to compare interactions between groups of people. I transcribed conversations between a group of friends at UCLA that consisted of two men and two women to see if we could find a gendered difference in their use of supportive overlap, or if this difference was due to another factor like relationships. I was curious as to whether differences in participants’ gender, or another factor such as their relationship to each other or even the type of conversation they are engaging in, affects their use of supportive overlap in a conversation.

Introduction: What are we studying?

Methods of cooperative communication are present in daily conversations and can be utilized to discuss linguistic differences in groups of people. It includes interjections such as “yeah”, “uh-huh”, and “okay” during a conversation not for the user to take over the conversation, but rather to show support (Tannen 1995). This concept is different from the traditional interruption, which requires the interrupter to talk over a speaker with the intention of terminating their turn speaking (Tannen 1994). The use of supportive overlap has cultural variations as well, as its use was detected more on the island of Antigua than a larger country like England (Tannen 1995). This device was also examined among a group of coworkers at lunch, and White 2003 noted that it was a common linguistic device used in enthusiastic conversation. One of the only studies that examined this supportive overlap in a gendered context is Coates (2003), who looked at the use of overlap among a group of women to determine it’s highly utilized in conversations between women. While previous literature looks at the presence of overlap in a variety of contexts, there remains a content gap regarding its appearance among a group of friends consisting of both genders. The following study serves to examine the relationship between supportive overlap and gender while simultaneously accounting for alternative factors such as conversation type and relationship. Supportive overlap is used primarily among women among a group of friends in order to show support during vulnerable parts of conversations while simultaneously portraying them as a supportive person.

Methods: How to Count the Uncountable

To probe the topic of gendered supportive overlap I audio recorded a group of friends with the same major at UCLA discussing three topics. The group is composed of two men and two women to observe if the difference is overlap is due to gender. I accounted for other variables that could explain the data outside gender, so the group consists of a couple as well.

I wanted to see if the familiarity within the group rather than gender accounts for this linguistic difference in speech. The group thus consists of a group of friends: Javier (male), Geoffrey (male), Tara (female), and Lilia (female). Javier and Lilia are a couple, while the rest of the group are all friends with each other.

I created three situations for the group to discuss: a neutral case, a case more commonly discussed among men, and one among women. The neutral or control topic is one they are all comfortable with: physiology. The following conversation involves controversy in the makeup world, which tends to be a female dominated industry. The final conversation involves controversy among weightlifters, which tends to be a male-dominated discussion and more prevalent among their daily conversations than women. The CDC notes that only 20% of American college woman meet the strength training recommendations while 37% of college men do (CDC). The three questions were constructed as follows: 1. What is the hardest physiology class you have taken?, 2. You are weightlifting at the gym and see someone with incorrect form: what do you do?, 3. Do you think makeup is necessary in the workplace to appear presentable and why?

I collected both qualitative and quantitative data regarding supportive overlap from 6 minutes of each conversation. I counted the number of supportive overlaps based on Tannen’s definition used by each individual in terms of both their gender and relationships and transcribed the data.

Qualitative Analysis: Who Said What

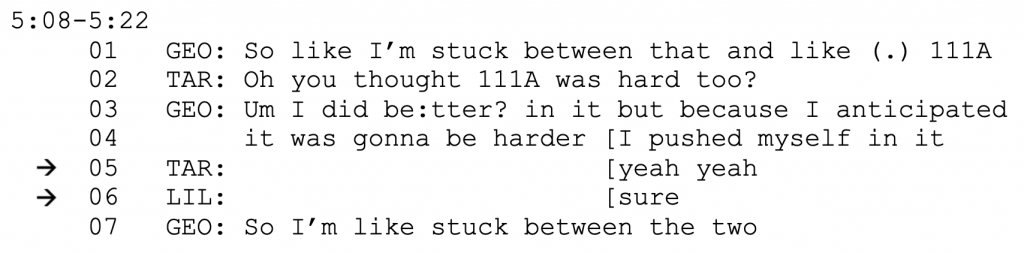

The first case involves opinions on the hardest physiology class at UCLA. Prior to this interaction, Tara had already elicited that she believed the hardest physiology class at UCLA was Physiological Sciences 111A, while Lilia selected a different class entirely.

This case differs from the rest because it shows two women overlapping the speaker. Geoffrey shows a face-threatening act in lines 3 and 4 by explaining a class traditionally found difficult was easier for him, which can appear as bragging. We see his discomfort with the use of uptalk and elongation of the word “better”. Both Tara and Lilia overlap him with positive words to reassure him and show that his social standing is not in question.

This case differs from the rest because it shows two women overlapping the speaker. Geoffrey shows a face-threatening act in lines 3 and 4 by explaining a class traditionally found difficult was easier for him, which can appear as bragging. We see his discomfort with the use of uptalk and elongation of the word “better”. Both Tara and Lilia overlap him with positive words to reassure him and show that his social standing is not in question.

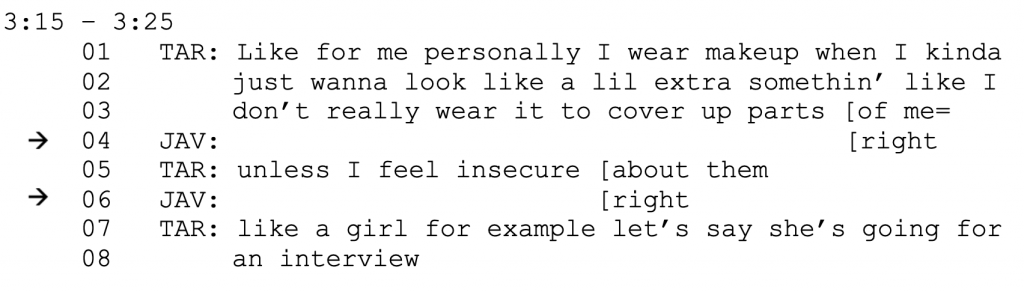

The next case examines a conversation about makeup. This conversation arose when they reached a disagreement about the necessity of makeup in the workplace. The following interaction shows Tara’s explanation as to when she chooses to wear makeup.

Tara’s anecdote was used to illustrate her experiences, which are not ones shared by Javier. She expresses vulnerability and thus a face-threatening act by discussing why she wears makeup. In lines 3 and 5, she explains how some wear makeup to “cover up parts” or when “[she] feel[s] insecure”. As a result, Javier says “right” in both lines 4 and 6 immediately following Tara’s displays of vulnerability to illustrate his support for his friend. Tara never previously showed hesitation in her speech, so the use of overlap shows attentiveness and encouragement. Additionally, the use of “right” rather than “sure” and “yeah” carries stronger weight and allows Javier to help alleviate the vulnerability displayed.

Quantitative Analysis: Tallying Up the Overlaps

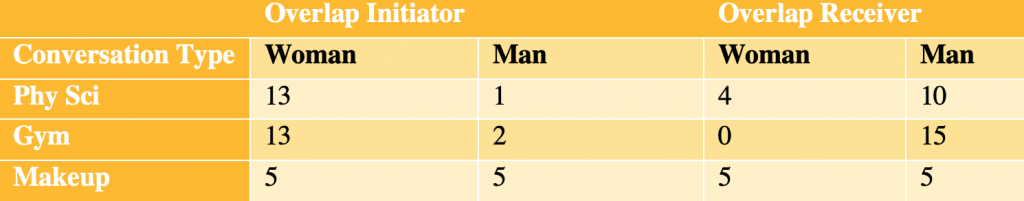

In the first two conversations, women appeared to initiate more overlap and especially toward men (Table 1). In the third conversation, this trend seems to somewhat dampen. A possible explanation could be explained by the men’s lack of topic familiarity and desire to show support for their female friends. It can also be explained because by the end of the study, Lilia was less talkative due to pulling an all-nighter the evening before.

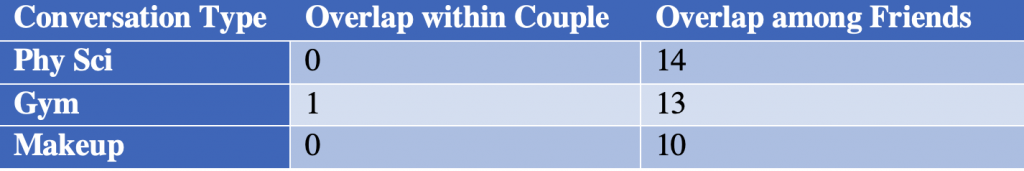

When analyzing the data in the context of a relationship, I found little to no overlap within a couple. One possible is the unnecessary need for the couple to use linguistic devices like overlap to show their support and attentiveness toward each other.

Discussion: So what does this all mean?

Conversational analysis among UCLA friends offers evidence of some gendered and relationship difference in the use of supportive overlap during three controversial conversations. Upon further analysis of their conversations, supportive overlap is used to not only show support in a conversation but also to provide assurance during a vulnerable conversation or face-threatening act. Quantitative analysis of the data shows that in 2/3 conversations, women utilized supportive overlap far more than their male counterparts. When rearranging the data based on individuals’ relationship to each other, there is significantly more overlap between friends rather than the couple. While no previous data on such interactions occur, I believe further research on this topic could prove worthwhile.

So what can this all mean? In Ochs & Taylor (1995), we see that the stereotype that women are the more supportive gender was perpetuated by the use of introductions by mothers in dinnertime conversation. Although this study does not look at the use of introduction, this stereotype of women being the more supportive gender is also illustrated in the context of this group of friends in a similar manner, but through the use of cooperative overlap.

I propose more extensive future study to probe the gendered use of supportive overlap in the context of multiple variables.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhis/earlyrelease/earlyrelease201212_07.pdf

Coates, J. (2003). Women Talk: Conversations Between Women Friends, London, Blackwell Publishers, 1996, 324 p. Clio, (11). doi: 10.4000/clio.228

Ochs, E & Taylor, C. (1995). The “Father Knows Best” Dynamic in Dinnertime Narrative.

Tannen, Deborah (1994). The relativity of linguistic strategies: rethinking power and solidarity in gender and dominance. In Gender and Discourse, ed. by Deborah Tannen, 19-52. Oxford University.

Tannen, D. (1995). Conversational style: analyzing talk among friends. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

White, A. (2003). Women’s usage of specific linguistic functions in the context of casual conversation: analysis and discussion. University of Birminghan.