Justine Jue, Myra Abdallah, Julia Gevorgian, Ryan Bowman

Alcohol consumption does not just affect the way you may act, but can also have a great effect on what you say as well. In this study, we determine how alcohol consumption affects the ways young adults communicate and articulate their speech. Our research focused on articulation, speed of speech, communication fluidity, changes in intonation, and creativity of responses. Given previous research that analyzes how alcohol can affect communication style and speech, we anticipated to find differences in the way individuals communicate when drunk versus when sober. Our research was focused on students attending UCLA ages 21-23 and looked at their speech patterns as they read a provided quote and analyzed their responses when asked to conduct an email when drunk versus sober. Our study provided interesting results following the interviews conducted with our willing participants showing that there is a noticeable difference in communication and speech style following intoxication.

Background

At the age of 21 years old, upon reaching the legal drinking age, young adults begin to indulge in drinking among peers, boosting their sociability. With social drinking being at an all-time high for individuals of this age group, differences can be examined in the way that people communicate when they are intoxicated versus when they are sober. Alcohol is known to have a considerable effect on cognitive ability and motor coordination, which in turn impairs speech production (Hollien et al., 2001). Research conducted on the impact of alcohol on first and second languages has indicated that inebriated individuals are likely to have slower speech and problems articulating their thoughts into words (Offrede et al., pg.683). Other studies have also demonstrated the ways in which alcohol consumption affects speech. In a study by Tisljár-Szabó et al., it was found that subjects made significantly more speech errors and took more pauses when speaking in an alcohol-influenced state (Tisljár-Szabó et al., 1989). Similarly, a study conducted by Martin and Pisoni found that alcohol consumption had considerably reduced subjects’ speaking rate as they prolonged vowels and consonants (Martin & Pisoni, 1989). In summary, research on this topic has generally concluded that intoxication causes articulation rate to decrease, pauses to increase, and more speech errors to be committed. In conducting our own research and collecting our data, we expected to find similar results consistent with previous studies. For our project, we hoped to explore the ways in which alcohol consumption might affect speech articulation and communication.

Methods

To determine the effect of alcohol on speech, we each interviewed three of our friends, who are UCLA students ranging from the ages of 21-23. Our study was a within-subject experiment as we used the same subjects for the sober and drunk parts of our study to help ensure internal validity. In “Effects of alcohol on the acoustic-phonetic properties of speech: Perceptual and Acoustic Analyses. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research,” they stated that having the participants experience every level of your study for this specific design will give you the most reliable results (Martin & Pisoni, 1989). To collect our data, we had our friends read a passage aloud and verbally pretend to write an email to a professor asking for an extension on an assignment while sober. With their permission, we audio-recorded them while they spoke so we could analyze their speech patterns. We listened and took notes of each participant’s audio recording, sober and drunk, and compared notes afterward. We wanted to see whether there were differences in the speed of their speech, the words they used, and how they pronounced their words sober versus drunk. We chose this way of interviewing our friends to answer our research question because, normally, one’s responses vary when they are drunk, so our two methods would exemplify what we were looking for.

Results and Analysis

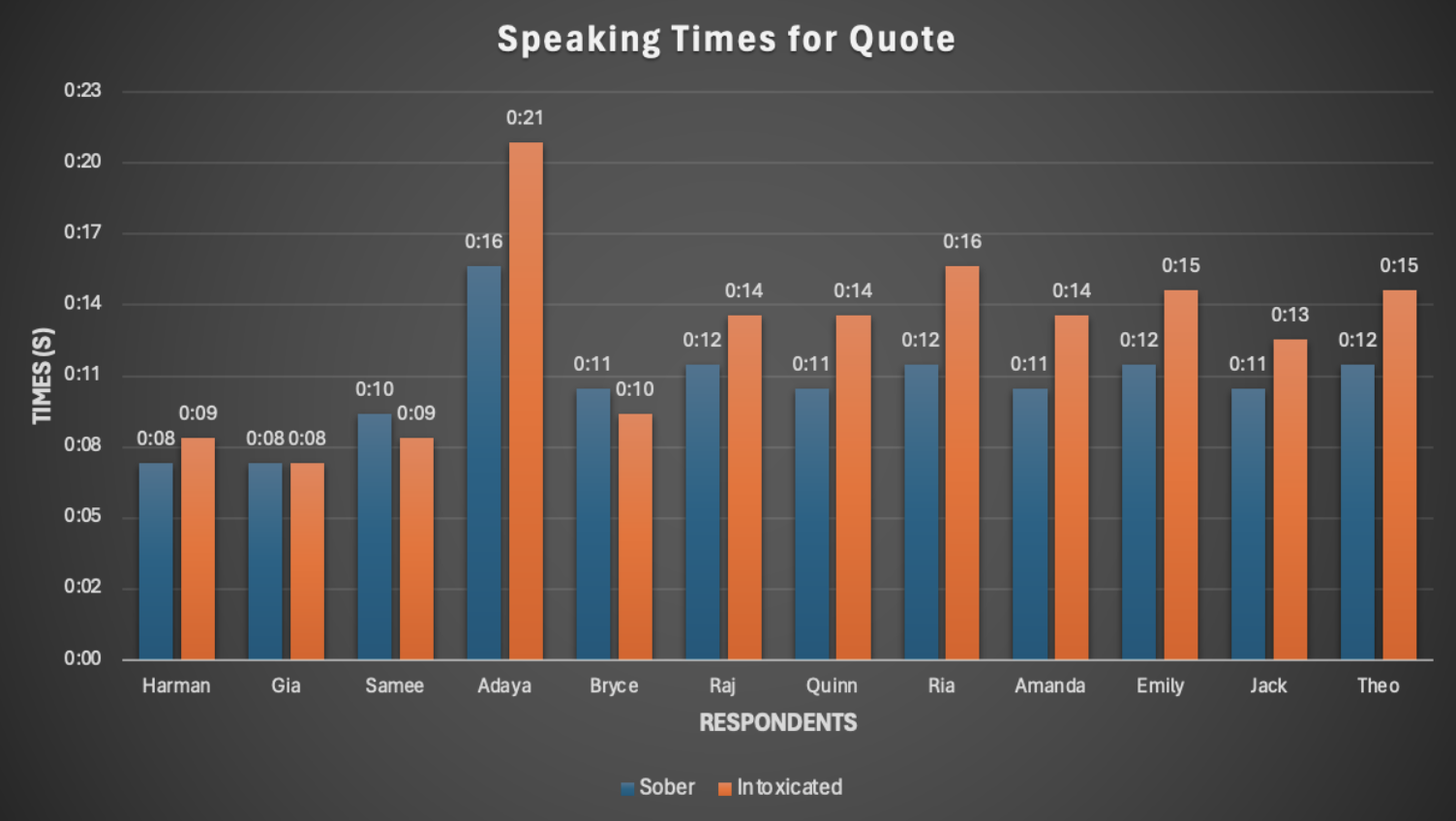

When collecting and analyzing our data, we found differences in the way that our participants read the provided quote in a sober state versus an intoxicated state. When intoxicated, 2 participants read the quote faster, 9 participants read the quote slower, and 1 participant read it at the same rate. Among most of our participants, alcohol consumption caused a decrease in articulation rate, which is consistent with the findings of previous studies.

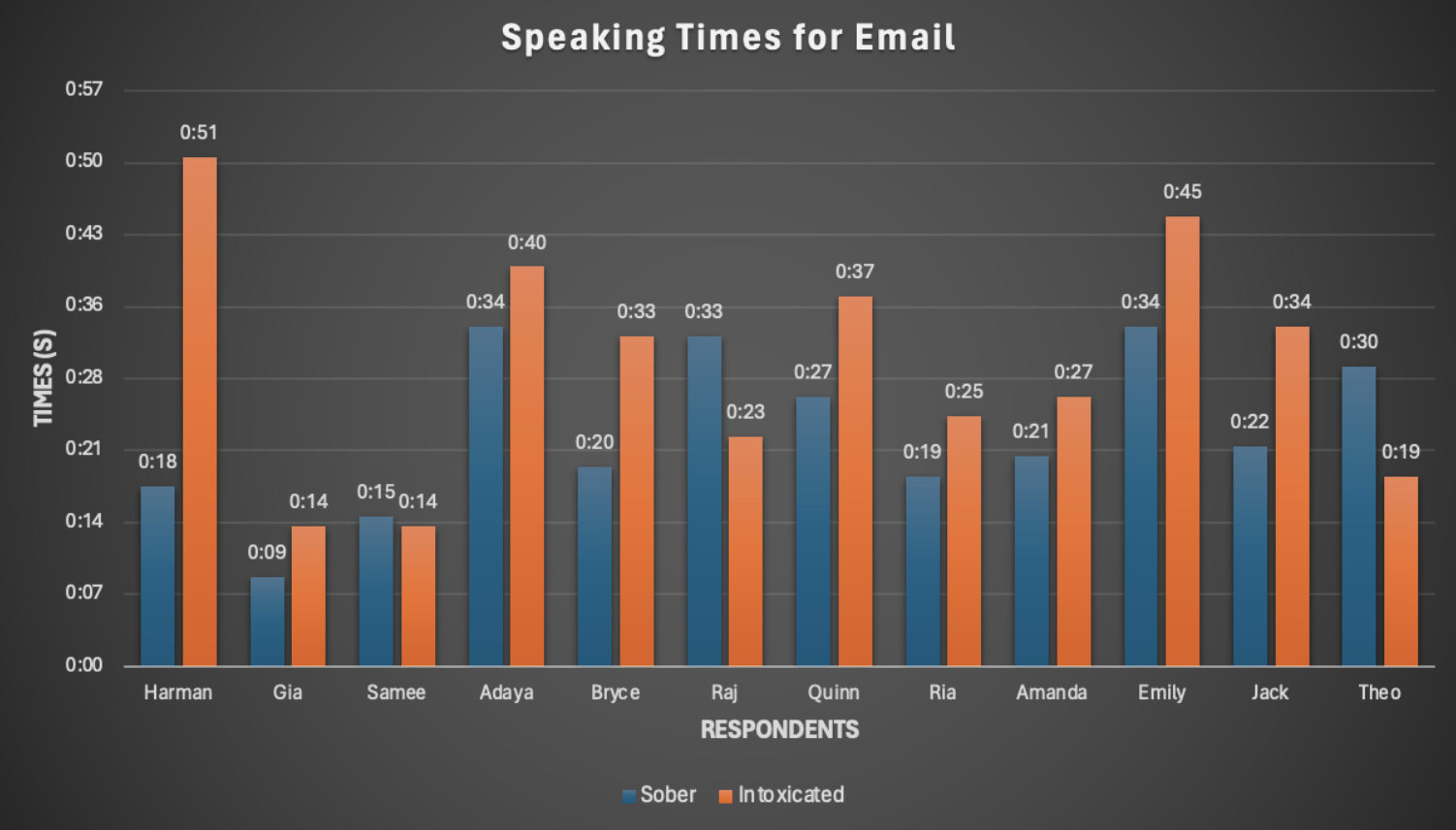

For the email portion of our study, we saw many of our participants show changes in their speech when they were sober versus drunk. Some of the main differences we viewed were the number of words they used and the creativity of their responses. For example, while recording the verbal email sober, one participant talked for 18 seconds about how they would ask for an extension. In their response, they were direct, concise, and used professional language. However, when they did this part again while intoxicated, they talked for 51 seconds. This same participant was also much more creative in their response while intoxicated and paused frequently. Additionally, each participant became much more casual with their speech, and many of them exemplified a great amount of laughter and enthusiasm in their responses when they were intoxicated. One of the last differences we saw while intoxicated was that participants started utilizing filler words such as “um” and “like,” which caused more pauses in their responses. Overall, there was a notable difference in our participants’ responses when drunk versus when sober, with our participants loosening their communication styles.

Discussion and Conclusion

While conducting our research and looking at our results, we realized the limitations that occurred during our experiment. Although we found there to be differences in speech within each respondent from being sober and intoxicated, these differences varied as the level of intoxication was different for each respondent. This is because even when trying to control the amount of alcohol we gave each respondent, the variation in height and weight of each of the respondents affected how intoxicated each individual got. Another possible limitation was that the respondents had knowledge that they were being studied, which may have resulted in them trying to control their responses more and concentrating more on the words and phrases they were saying. This could also result in them exaggerating certain things when speaking to make it seem like they were either more intoxicated or sober than they actually were. Finally, even though our results show that alcohol is able to cause differences in speech, our study only focused on young adults as respondents. As a result, the research that we did may not be an accurate representation of the effects alcohol has on speech for the general public, as there may be variations with age that could occur.

With the consumption of alcohol, we found that our participants’ tone, speed, words chosen, and focus were all affected for some more than others. For some individuals, these components varied, with some having no change, some having changes in some areas, and others having all these changes present in their interview. In “Alcohol’s Effect on Some Formal Aspects of Verbal Social Communication,” Smith et al. were interested in the variation that the dosage of alcohol provides for the level of inability to communicate in comparison to when sober (1975). Our research supported Smith et al.’s findings in that alcohol did have an effect on the way individuals communicate (1975). Their findings suggested that even in low doses of alcohol consumption, there were differences in the way that their participants communicated when drunk versus when sober. Our findings were similar in that when our participants consumed alcohol, there was a noticeable difference in communication. Individuals consuming alcohol are, therefore, likely to have an impact on the way they communicate, whether great or minimal. The way people articulate their sentences, their tone, the speed of their speech, their focus, and even the words chosen are all components that are likely to be affected by alcohol intoxication.

References

Hollien, H., DeJong, G., Martin, C., Schwartz, R., & Liljegren, K. (2001). Effects of ethanol intoxication on speech suprasegmentals. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 110(6), 3198–3206. DOI: 10.1121/1.1413751.

Martin, C. S., & Pisoni, D. B. (1989). Effects of alcohol on the acoustic-phonetic properties of speech: Perceptual and Acoustic Analyses. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 13(4), 577–587. DOI: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00381.x.

Offrede, T. F., Jacobi, J., Rebernik, T., de Jong, L., Keulen, S., Veenstra, P., Noiray, A., & Wieling, M. (2021). The impact of alcohol on L1 versus L2. Language and speech, 64(3), 681-692. DOI: 10.1177/0023830920953169.

Smith, R. C. (1975). Alcohol’s Effect on Some Formal Aspects of Verbal Social Communication. Archives of General Psychiatry., 32(11), 1394–1398.

DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760290062007.

Tisljár-Szabó, E., Rossu, R., Varga, V., & Pléh, C. (1989). The Effect of Alcohol on Speech Production. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 43(6), 737–748. DOI: 10.1007/s10936-013-9278-y.