Talla Khattat, Jacob Gutierrez, Edna Tovar, Grace Yang, Al Jackson, Espie Maldonado

Why do all military characters in animation films have Southern accents? Throughout this blog, we aim to understand the world of languages in animated films and take you along with us. Audience members digest the creative choices that are made on screen and unconsciously learn to associate linguistic patterns with certain sociocultural elements. This research paper aims to observe the linguistic elements of accents and dialects to understand the correlating relationship with the language ideologies and cultural attitudes. We observed the films Aristocats (1970), The Secret of NIMH (1982), The Rescuers Down Under (1990), and Zootopia (2016), and categorized the different patterns observed based on several different elements. Our findings show that minority accents can be tokenized to invoke assumptions about a character in order to save screen time. We call on future research to understand how impactful some of these harmful depictions can be and emphasize the importance of respectful representation.

Introduction and Background

Many would agree that animated films are a huge part of one’s childhood. From Disney princes and princesses to a mice version of the United Nations, everyone enjoyed their fair share of animated movies. The beauty of animation is the freedom to shape an entire world from the ground up, where every character is completely designed from scratch, and every choice, from costume, to music, to voice is made intentionally. With this freedom also comes challenges with needing to establish connections from what is seen on screen with the minds of the audience. From the start of the film, the creators need to quickly establish character relations and connections. Here, they use language shorthands that the audience is indirectly familiar with to signal the persona of the character. Our group’s research question aimed to understand throughout a series of animated films what traits or roles are typically associated with certain accents, language varieties, styles, or registers? Within this realm, we also wanted to understand how Standard American English would be treated compared to other accents or dialects. We hypothesized that non-standard varieties of English/Non-English will be associated or invoked when connected to ‘bad’ or side characters, while standard American English will be most often connected to ‘good’ characters or protagonists.

Previous research has indicated that the cultural value of individualism in the United States is reflected in the use of standard English, which often leads to a lack of tolerance towards other languages or English language variations (Wiley, 1996). Although Disney animated films are often translated into standard English, it hinders the complexity of modern language and erases many cultural elements (Bruti, 2009). Moreover, we have also found that language elements can be used to invoke association about certain groups of people in film. Previous work completed by Meek shows how language and race perform character portrayals and as the audience, we witness this work that is being “done”. (Meek, 2006). In other words, accents are often used to not only demonstrate an ethnicity, but also substantiate a portrayal of a certain stereotype associated with a certain group of people.

Methods

To gather data about the language ideologies and characters linked to them, we analyzed four different films; The Aristocats, The Secret of NIMH, The Rescuers: Down Under, and Zootopia. Particularly, we noted what accents and languages were used (or created) in these films and what characters or themes they were associated with. We chose to focus on animated animal characters since we felt that filmmakers could ‘get away with more’ and because language is the main humanizing factor in animal characters, we could better see how language/accents were being used to invoke assumptions about the character.

Watching the movies completely through and inspired by the methodology of a paper written by Janne Sønnesyn, we then categorized our character findings into several categories including their: language/accent, role in the movie, costume, character features, gender, and other distinguishable elements. In sum, we analyzed 66 characters along these 6 categories.

Moreover, by codifying our analyses, we can answer the research question, what traits or roles are associated with certain accents, language varieties, styles, and registers? How do the filmmakers express differentiation amongst characters through the use of language and character design?

Results and Analysis

After empirically analyzing our data, we found several patterns that confirmed part of our hypothesis and refuted others. We looked at our data as an aggregate, combining the findings from all four movies and examining the results in this way.

First Result

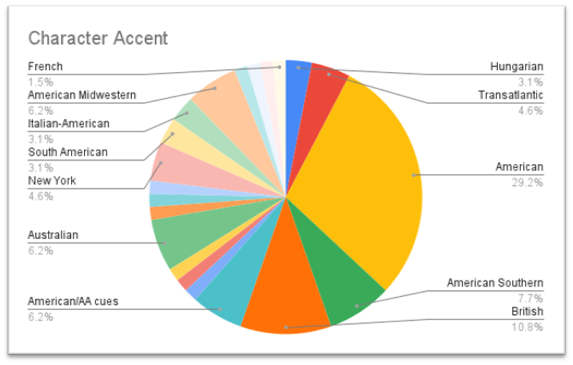

Referencing Figure 1 which provides a visual representation of the distribution of the observed character accents, we were able to establish four distinct results. Firstly, we found that the protagonist(s) of the films indeed were associated with the American Standard English accent 54% of the time. Furthermore, 100% of the protagonists had European or American accents — in other words, no minority population accents were represented in the protagonists of these films.

Second Result

This point leads to a second key finding that minority population accents were typically attached to side characters. In fact, 64% of all side characters had a minority accent. Put differently, minority population accents were overrepresented in this character role and underrepresented in others. Heroes did not tend to have minority population accents. Notably however, no antagonist had a minority population accent either — which refuted part of our hypothesis.

Along the same lines as our minority population accents, non-rhotic accents (accents that ‘drop’ the pronunciation of ‘r’), were commonly used in connection to characters of low socioeconomic status or working class. Some examples of these non-rhotic accents were the New York accent and AAVE (African American Vernacular). We noted 5 characters that used a non-rhotic accent; 3 were associated with petty crime,1 was a working-class shop employee, and 1 was a ‘street’ cat (what we interpreted as houseless for our analysis). Figure 2 depicts one such character from Zootopia, Duke Weaselton, who has a New York accent and is one of the movie’s shady characters — involved in thievery, bootlegging, and evading arrest.

Third Result

Another pattern that emerged was the use of the American Southern Accent to invoke themes of militarism, violence, and unintelligence. Of all 5 characters observed to have the American Southern Accent, 2 were antagonists, 4 invoked themes of militarism (deduced through plot; such as one of the antagonists, McLeach —figure 4 — having the American Southern Accent and a past in the military), and 3 were displayed as unintelligent (deduced through plot — such as one character with the American Southern Accent calling, as seen in this clip (“It’s In My DNA – Zootopia” ‘DNA’, “dunnuh”).

Fourth Result

The final pattern that we noticed through our data is that ‘sophisticated’ characters had American and European accents 88% of the time. We coded ‘sophisticated’ as characters that were portrayed as respected, legendary, wise, or graceful, which we deduced through plot and surrounding character reactions. For instance, one character in The Secret of NIMH was sought out in answer to the protagonist’s dilemma, since they were canonically ‘all-knowing’ and powerful. Of the 9 characters we coded as ‘sophisticated’, only one did not have an American or British accent.

Discussion and Conclusions

This study offers insights into the impact of accent features on stereotypes among animal characters in animation. While we cannot definitively speak on behalf of the filmmakers as to whether these depictions were intentional, we establish these findings as results of our observations. Furthermore, we recognize that these choices could be made subconsciously.

Media is one of the greatest socialization agents. Animated films play a huge role in influencing children’s perceptions of the world and other people. With repeated representation of problematic stereotypes, viewers will believe they are true. Our data spans 46 years, emphasizing that while progress has been made, there is a long way to go. While there are less explicitly harmful linguistic stereotypes being utilized, it is still true that protagonists consistently speak with ASE while side characters are relegated to minority accents. The biggest difference throughout time is a diversification of accents, but their distribution has remained the same. We must also consider the level of authority as a source of knowledge Disney has. For those who do not question the status quo, they are even more likely to believe in stereotypes when they come from a ‘reputable’ source like Disney. For this reason, it is crucial for filmmakers and powerful studios to be responsible and inclusive with the media they produce.

To further broaden our understanding of this phenomenon, it would be worthwhile to extend research to human characters in Disney animated films. According to Brous, this type of linguistic stereotyping occurs in films such as Frozen, Coco, and Moana (2020). It is clear that the negative representation through accents extends further than cartoon animals. Søraa’s work would be useful to explore a film like Brave, where the setting itself contributes to reflecting stereotypes portrayed through linguistic markers (2019). With regards to minority cultures, Towbin et al. would serve as a resource to study how non-dominant cultures are represented negatively, which can be seen in Pinocchio, Alice in Wonderland, Peter Pan, Oliver, and Aladdin (2004).

It is also essential to acknowledge the issue of stigmatization of the female characters in Disney movies, as highlighted by Soares (2017). According to Växjö (2014), Disney princesses exhibit many stereotypical linguistic features, so their characters adhere to the traditional gender roles and expectations. Moreover, it is important to examine the impact of misrecognizing accents and linguistic features in television and how it might affect child viewers, causing them to internalize negative stereotypes portrayed in animated programs. Wenke’s article (1998) can serve as a source for exploring how children’s attitudes towards people and activities can be influenced by the portrayal of linguistic elements in television programs.

In the end, the impacts of animated films and the representations of different peoples, cultures, and identities can have long-lasting impacts on the people, more importantly children who watch animated films. While it’s not a direct issue, the unintended consequences of filmmakers, animators, and writers have an important job in creating media that is representative, respectful, and for audiences of all ages, as many animated forms of media have previously encouraged and helped spread harmful stereotypes of minorities for decades.

References

Accents in children’s animated features as a device for teaching children to ethnocentrically discriminate. (2019). Upenn.edu. https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/popcult/handouts/wenkeric.htm

Bluth, D. (1990). The Secret of Nimh. Sulivan Bluth Studios.

Brous, S. (2020, December). “Frozen” In Time: Dialect and Language Ideology in Disney Films (thesis). Tri College Department of Linguistics. Retrieved from https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/bitstream/handle/10066/23186/Brous_thesis_2020.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Bruti, Silvia. (2009) From the US to Rome Passing through Paris. InTRAlinea. Online Translation Journal > Special Issues > Special Issue: The Translation of Dialects in Multimedia > From the US to Rome Passing through Paris http://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/From_the_US_to_Rome_passing_through_Paris.

Meek, B. A. (2006). And the Injun Goes “How!”: Representations of American Indian English in White Public Space. Language in Society, 35(1), 93–128. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4169479

Reitherman, W. (1970). The Aristocats. United States; Walt Disney Pictures.

Schumacher, T. (2012). The Rescuers Down Under. United States; Walt Disney Pictures.

Søraa, I. (2019, May). The Sound of Disney (thesis). Master’s thesis in Language Studies with Teacher Education. Retrieved from https://ntnuopen.ntnu.no/ntnu-xmlui/bitstream/handle/11250/2623375/no.ntnu:inspera:2276305.pdf?sequence=1.

Soares, T. (2017). Animated Films and Linguistic Stereotypes: a Critical Discourse Analysis of Accent Use in Disney Animated Films Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Soares, Telma O. (2017). Animated Films and Linguistic Stereotypes: a Critical Discourse Analysis of Accent Use in Disney. https://vc.bridgew.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1053&context=theses

Spencer, C. (2016). Zootopia. United States; Walt Disney Animation Studios.

Towbin, M. A., Haddock, S. A., Zimmerman, T. S., Lund, L. K., & Tanner, L. R. (2004). Images of gender, race, age, and sexual orientation in Disney feature-length animated films. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 15(4), 19–44. https://doi.org/10.1300/j086v15n04_02

Wiley, T. G., & Lukes, M. (1996). English-Only and Standard English Ideologies in the U.S. TESOL Quarterly, 30(3), 511–535. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587696

Växjö, Kalmar (2014). Happily Ever After: A Linguistic Study of the Portrayals of the Female Characters in One Old and One New Disney Princess Film https://www.divaportal.org/smash/get/diva2:795579/FULLTEXT02.pdf