Jessica Nepomnyshy, Andrew Gerbs, Christabel Odoi

Language is often considered a window into a culture, but what happens when that window starts to close? In many families, heritage language communication can be a complex and nuanced issue, especially when it comes to older and younger siblings. While the older generation may have grown up speaking the language fluently, their younger siblings may struggle to maintain their proficiency. Data was collected and analyzed, showing the trend that older siblings were more proficient than their younger siblings when communicating with their parents in their heritage language. This correlates with our background research which discusses sibling language proficiency and code-switching within bilingual families. We explore the communicative differences between parents and their children, and how confidence when speaking, code-switching, and understanding of the heritage language all play small roles in the relationship children have with their parents. Our main findings indicated that the younger siblings had less proficiency and that parents were more likely to support heritage language use with their older child, which could create a closer relationship between them.

Introduction and Background

A few questions we aimed to understand were: When examining heritage language communication between a parent and their second-generation children, is one sibling more proficient than the other when corresponding with the parent? Are communication dynamics and abilities differing between siblings, and? How is the confidence and language style of one sibling different from the other sibling when in communication with the parent? We hypothesized that if the older sibling is more proficient in the heritage language than the younger sibling, then the parent often will encourage the less proficient sibling to communicate more in the heritage language as one may avoid using the language due to difficulty.

Siblings play an important role in shaping the overall language environment within immigrant families, and their language choices influence the family language policy. Older siblings often act as language experts and help younger siblings develop their language skills (Kheirkhah & Cekaite, 2017). However, younger siblings may find it easier to use English over their heritage language, leading to more code-switching, which is defined as the alternation between two or more languages in the context of a conversation or situation.

Heritage language ties how siblings communicate with their parents as data has shown that bilingual Chinese language speakers strived to maintain their language due to their parents’ wish for them to know Chinese strongly. Language is the factor that facilitates communication between family, siblings, and spouses (Budiyana, 2017). Heritage language is important as it strengthens and reinforces bonds with the heritage community and leads to greater overall connectedness with family and friends who also speak the language (Vallance 2015).

Methods

We explored data from five bilingual families: one parent and two children with varying proficiencies in a heritage language. All participants signed a consent agreement (parents signed for their adolescent children under 18) and completed a survey that functioned both as a pre-selection tool and a way to gather relevant socio-demographic info, where asked age of all participants, all languages spoken, and amount of years the language has been spoken. Names and any identifiable information were removed to maintain participants’ anonymity.

Parents were asked to sit down with each sibling and audio-record a conversation in the heritage language to the best of their abilities, asking for up to ten minutes of audio recording. The parent was asked to maintain the flow of the conversation by asking follow-up questions when their child responded to the question posed to observe a more natural conversation. We tasked each parent and sibling to answer three conversational questions: “Tell me about your favorite part of your day today,” “Let’s discuss a movie TV show that you recently watched that you enjoyed,” and “What is your favorite thing to do on the weekend?” By gathering audio recordings, we were able to notice differences between the pairs of siblings in comparing the number of times each sibling code-switched, their confidence levels, and whether a sibling self-corrected or if a parent was inclined to correct their child when errors were made. Through observing these three key features in heritage language-speaking siblings and their conversations with a parent, we can better understand the role language holds in maintaining a relationship between siblings and parents.

Results and Analysis

From our five sets of participants, one parent and two siblings per set, we transcribed, counted, and observed the frequency of each sibling’s code-switching from their heritage language to English. From this data, we counted the number of code-switches that younger siblings produced and calculated that on average they would switch to English twelve times in ten minutes, which is around 83% of the time. When the same method was used to count and calculate for the older siblings, we concluded that they code-switched on average seven times within their ten-minute conversations, equaling 70% of the time.

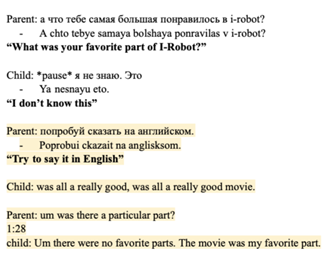

Through observing code-switching patterns, we noticed that parents were more likely to correct their older children when they made errors or code-switched from their heritage language to English. When it came to younger siblings, parents were more lenient in allowing their children to continue speaking in English as shown in an example in Figure 1.

The younger sibling in this example is asked by the parent to respond in Russian, and when the sibling responds in English, the parent continues to follow up in the non-heritage language. One can also observe that earlier in the transcript the younger sibling can say that they don’t know how to say something using their heritage language, right before code-switching to English. The younger sibling also seems to avoid giving many details when speaking, as they are less confident in using the heritage language throughout their speech. One can observe this when the sibling uses a filler word before reiterating the same two responses to their parent.

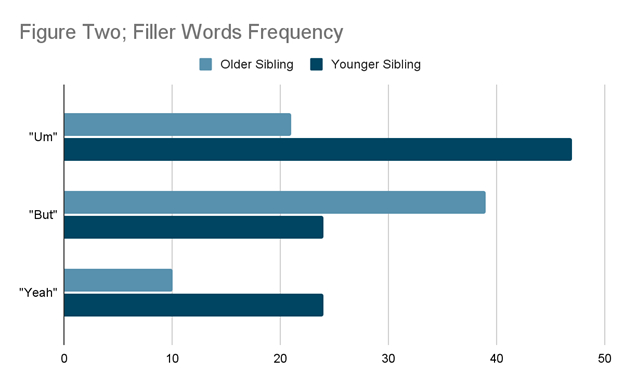

We observed noticeable differences in confidence levels between siblings when conversing with parents in the audio recording. Siblings used filler words like, “um” “but” and “yeah” which indicated how sure one was when answering a question. This analysis revealed that higher usage of filler words showed that a sibling was less confident in using their heritage language when answering questions. We counted the number of filler words used throughout all interviews and showed them in Figure 2.

This data was collected to validate our results as we compared the number of filler words used to the level of confidence siblings showed in their language use. “Um” was used significantly more than “But” and “Yeah” as it was used as a break when one was thinking of more dialogue. “But” was used significantly more by the older sibling and was observed to occur before or after they code-switched to transition back to the other language. “Yeah” was used less often, but was an indicator used when one was finishing a train of thought. Many siblings had limited vocabulary when speaking, so it was imperative to our study to track the number of filler words.

Discussion and Conclusions

Researching heritage language maintenance within families opens one’s eyes to the efforts parents make to preserve and pass on their language to their children. Many aspects play into siblings’ understanding, communication, and confidence when using a heritage language, and we as researchers were able to uncover differences between how older and younger siblings communicate with their parents. The hypothesis we explored was that older siblings are more proficient in the heritage language as compared to the younger siblings, and because of this, the parents would encourage the less proficient sibling to communicate more in the heritage language as a way to improve their language skills. After observing a variety of communication aspects between siblings and parents, we were able to conclude that our hypothesis was partially true. We found that out of all our sibling pairs, every younger sibling was less proficient in speaking their heritage language, as they code-switched more often and exhibited less confidence through using filler words, in comparison to the older siblings who demonstrated a stronger grasp of the language. As researchers, we hypothesized that the less proficient sibling, within our data being the younger one, would be more likely to get corrected by their parents when making grammatical mistakes, or code-switching, but we were wrong. It was more likely that a parent would correct the older sibling’s heritage language use and allow the younger and less proficient sibling to speak English. We can consider the idea that parents are more likely to correct their older children as a way to preserve and maintain their proficiency, knowing that the younger sibling holds less strength in the language.

If we had more time to further this study, we would most likely broaden the number of subjects we had, provide deeper questions, and use surveys to gauge more attitudes on language use, and the impact it has on parent and child relationships. A few limitations that we did not consider were whether the genders of siblings played a role in their proficiency, if parents being immigrants played a role in proficiency, and whether the age at which the language was learned played a factor in subject experiences. We were able to conclude that older siblings were much more likely to be the stronger speakers when it came to using the heritage language, in comparison to their younger siblings. Unfortunately, we could not fully determine if parents had a closer bond with the more proficient children, but we can assume that they can connect more through bilingual communication.

References

Altman, C., Burstein Feldman, Z., Yitzhaki, D., Armon Lotem, S., & Walters, J. (2013). Family language policies, reported language use and proficiency in Russian – Hebrew bilingual children in Israel. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(3), 216-234. doi:10.1080/01434632.2013.852561

Budiyana, Y. E. (2017). Students’ parents’ attitudes toward Chinese heritage language maintenance. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 7(3), 195. doi:10.17507/tpls.0703.05

Kheirkhah, M., & Cekaite, A. (2017). Siblings as language socialization agents in bilingual families. International Multilingual Research Journal, 12(4), 255-272. doi:10.1080/19313152.2016.1273738

Nitta, F. (1996). Socialization of “International children”. Kazoku Syakaigaku Kenkyu, 8(8). doi:10.4234/jjoffamilysociology.8.97

SORENSON DUNCAN, T., & PARADIS, J. (2020). Home language environment and children’s second language acquisition: The special status of input from older siblings. Journal of Child Language, 47(5), 982-1005. doi:10.1017/s0305000919000977

Vallance, A. (2015, 12 21). The Importance of Maintaining a Heritage Language while Acquiring the Host Language. https://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=honorstheses#:~:text=Maintaining%20the%20heritage%20language%20strengthens,who%20also%20speak%20the%20language