Sylvia Hopkins

Content/Trigger Warning: This article discusses sexual assault

Social commentary has become much more common and impactful to everyday people and their lives. In current times, social commentary is mostly used in social justice spaces with the intent of raising awareness, educating people, or calling out people and institutions for problematic behavior. In the past, only academics and media broadcasters were able to social commentate on a large scale. Traditionally, social commentary was largely limited to class-privileged and college-educated people who were overwhelmingly white and male. The rise of the internet and social media has allowed people who would not have previously had the resources to share their ideas to now be able to broadcast their ideas to thousands, if not millions of people. Because of this new-found accessibility, there has been a huge increase in marginalized people creating and engaging in social commentary. The recent increases in accessibility are not only good for diversity, but also for subverting gender norms.

Introduction and Background

According to common gender norms, girls and women are expected to soften their language and avoid being direct, and to not employ harsh rhetoric. In contrast, boys and men are allowed and expected to not not soften their language, to be direct, and use harsh rhetoric. But these trends are not being seen in social commentary; female social commentators are routinely using harsh rhetoric and being direct with their wordage and their messaging, all while male social commentators are doing the opposite, they are regularly using soft and indirect rhetoric.

Social commentary is not something that has drawn the attention of many researchers, and the works that exist on it primarily deal with the potential political consequences and mass spread of misinformation. Gender and linguistics in social commentary spaces has not been properly researched, this project aims to fill in some of the gaps and provide understanding by analyzing videos from social commentators.

Methods

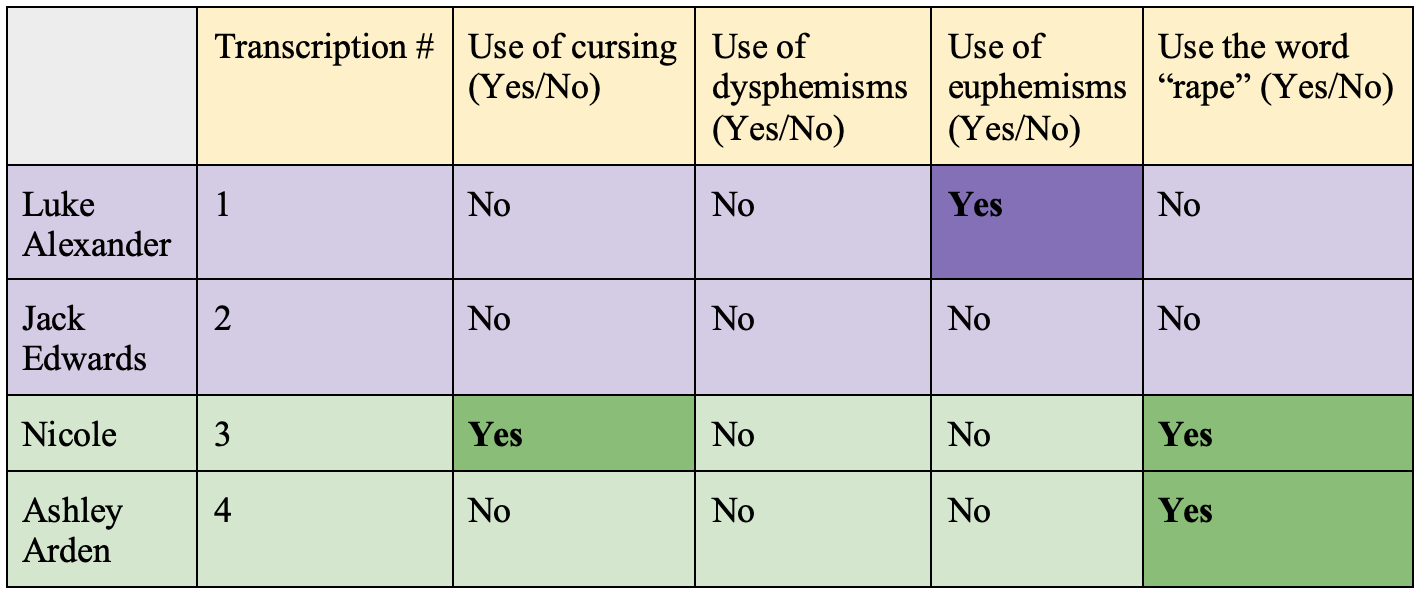

The design of this project was to transcribe four total YouTube videos from different social commentators, two female and two male, about the same topic and cross-analyze them. The common topic for this project was a sexual assault scene Bridgerton, a show that recently came out on Netflix, it was chosen because it was recent and stirred lots of pushback, criticism, and commentary. The sexual assault scene details Daphne sexually assaulting her husband, Simon, in an attempt to become pregnant. This scene was considered disturbing by a mass audience and all social commentators in this sample also found it disturbing. Cross analysis was based on the use of cursing, euphemisms, and dysphemisms.

The three linguistic features that were analyzed in this project are word choice (curse words), as well as euphemisms and dysphemisms. The use of curse words is relevant because cursing is considered in most spaces and contexts to be socially unpleasant and harsh. Cursing is something that men are not regularly punished for or discouraged from doing, while women are often told that cursing is not “lady-like”. Aditi Sharma explores the gendered double standards for cursing in her article Why Do Women Have Such Limited Swear Words To Ab(Use)? Euphemisms and dysphemisms are relevant because when someone uses an euphemism, they are trying to be less harsh and soften their words, while with dysphemisms, they are trying to make their words harsher for rhetorical effect.

Results

Transcriptions 1 and 2 both came from male commentators, Luke Alexander and Jack Edwards. Neither of them used cursing or dysphemisms, and one of them (Luke Alexander) used an euphemism. Neither of them used the word “rape”, Luke Alexander instead spelled out “R-A-P-E” to avoid saying “rape” or “sexual assault”. In contrast, neither of the female commentators used euphemisms and both of them used the word “rape” directly instead of using a euphemism or spelling it out like Alexander.

Transcriptions 3 and 4 came from female commentators, Nicole a.k.a. “A Seventeenth Grade Nothing” and Ashley Arden. As stated before they did not use euphemisms and both referred to sexual assault directly by saying “rape”. Nicole is the only commentator in this sample that curses. Ashley Arden’s states that this scene is “ugliest scene I’ve ever watched in a teen show”. Both Nicole’s and Ashley Arden’s commentaries are blunt and direct, neither of them use any linguistic feature to soften their tone, wordage, or message. This is the opposite for Luke Alexander and Jack Edwards, neither of them use the word “rape” and neither of them use dysphemisms.

Discussion

Each of the commentators are norm-breakers. Luke Alexander, Nicole, and Jack Edwards in relation to cursing. Nicole for her cursing, Alexander and Edwards for their complete lack of cursing. In Example 3, Nicole curses, this makes her a norm-breaker because it is considered socially unacceptable in many contexts for women to curse. Contrasting Nicole, neither of the male commentators use cursing, which makes them also norm-breakers in most non-formal settings, it is considered appropriate, and often expected for men to curse. Luke Alexander, Nicole, and Ashley Arden are norm-breakers with respect to euphemisms. Luke Alexander uses a euphemism when he refers to semen as “children juice” and spelling out rape instead of saying it directly. This goes against gendered norms because men are expected to use direct language when communicating, therefore to not use euphemisms. Neither Nicole nor Ashley Arden use euphemisms, which makes them both norm-breakers for not using euphemisms to soften their language, which is something women are expected to do. When women use direct language they can be labeled as “aggressive” or “masculine”.

Conclusion

The purpose of this research was to see if social commentary has created a space for people to subvert gendered linguistic norms and if so, what does it mean for society as a whole. The answer put simply is yes, people of different genders are shown to subvert gender norms, this was shown through looking at the use of cursing, euphemisms, and dysphemisms. This has significant meaning for society, because while gender norms, not just ones dealing with language, are being moved away from, they are still very present and often harm people.

The internet made the ability to social commentate so much more accessible than it had ever been, and this accessibility gave diversity, it gave voices that were not being listened to a way to be heard on a mass scale. Accessibility also gave women and men the ability to communicate to mass audiences in ways that violate gender norms, which is not only significant for the commentators themselves, but also the people that watch them. When people see people that mirror their identities subverting gender norms it gives a sort of permission to the viewer to do the same. This subversion of gender norms can allow people to express themselves more authentically without being punished or ridiculed. While having gender norms is not inherently evil, they are largely oppressive and tie into larger patterns of violence. When people violate gender norms, they can be subject to violence; there are countless examples of this, some of which are women being killed for being rude to men, men who engage in femininity are often the victims of hate-crimes, women being murdered in honor killings, and many more. Subverting gender norms with linguistics is subverting gender norms as a whole, and doing so makes society freer and safer.

References

Crespo-Fernández, E. (n.d.). Sex in Language: Euphemistic and Dysphemistic Metaphors in Internet forums. Bloomsbury Publishing. Retrieved February 6, 2021, from https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=iInaCQAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&d=Dysphemism+gender&ots=JeoliQi9La&sig=lTkW2xCP0sZu2YZzWv498Q8IgNY#v=nepage&q=Dysphemism%20gender&f=false

Definitions for social commentary. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2021, from https://www.definitions.net/definition/social+commentary

Info & Stats For Journalists. (2015). National Sexual Violence Resource Center

Kimmons, R., & Veletsianos, G. (2016). Education scholars’ evolving uses of twitter as a conference backchannel and social commentary platform [Abstract]. British Education Research Association, 47(3), 445-464.

Lapadat, J. C., & Lindsay, A. C. (1999). Transcription in Research and Practice: From Standardization of Technique to Interpretive Positionings. Sage Journal.

Orlando, E., & Saab, A. (2020). Slurs, Stereotypes and Insults. Springer Link, 599-621.

Popa-Wyatt, M. (2020). Reclamation: Taking Back Control of Words. Brill, 97(1), 159-176.

Rape culture & statistics. (2014, June 07). Retrieved March 8, 2021, from

Sharma, A. (n.d.). Why do women have such limited swear words to ab(use)? Retrieved March, 2021, from https://www.bingedaily.in/article/women-swear-words-sexist-patriarchy

Swanson, S. C., & Szymanski. (n.d.). From pain to power: An exploration of activism, the #Metoo movement, and healing from sexual assault trauma. Journal of Counseling Psychology.