Caroline Breckling

This study investigates to what extent individuals are able to identify a person’s ethnicity based solely on the sound of their voice. Expanding on previous research demonstrating humans’ relative accuracy in recognizing ethnicities by voice, this investigation aims to explore whether a listener’s own ethnicity or familiarity with other ethnicities affects their accuracy in this identification. My survey, conducted with 20 participants from diverse backgrounds, asked individuals to identify the ethnicity of speakers in six different audio clips. Results indicated that participants could identify the speaker’s ethnicity with an overall accuracy of 43.3%, significantly higher than random chance, and a majority of the time, this level of accuracy went up when the guesser was from the same ethnicity group as the speaker featured in the sound bite. However, familiarity with an ethnic group did not reliably improve rates of accurate identification. These findings reflect humans’ existing ability to recognize in-group members through minimal auditory information, reflecting the lingering effects of socialization for survival in human history.

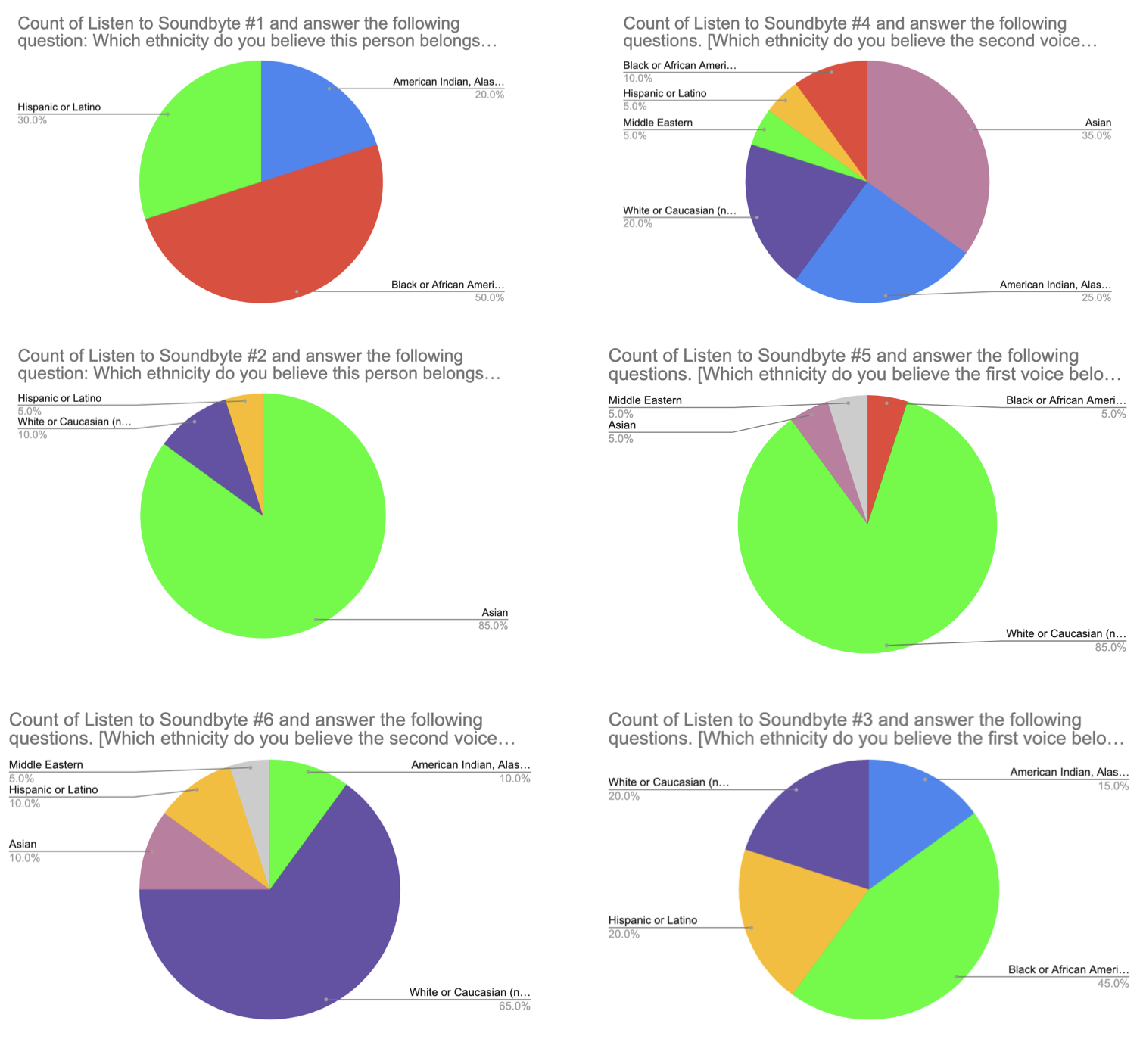

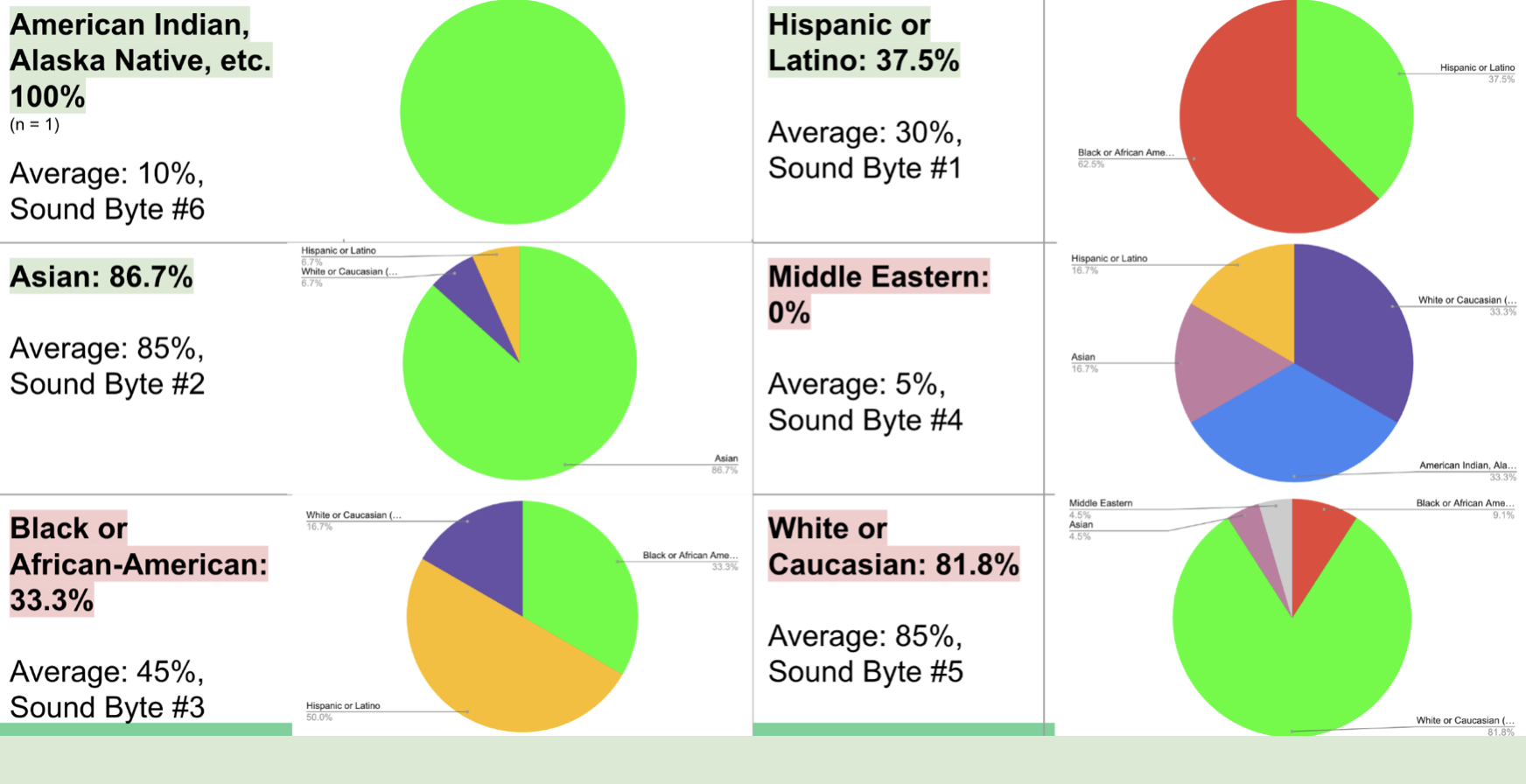

Introduction For my inquiry, I was curious about to what degree humans are able to identify another person’s ethnicity by only hearing the sound of their voice. Some pre-existing research reflected that people were relatively proficient in recognizing ethnicity by voice; in one study, 85.7% of participants could correctly identify Black voices, 75.5% could correctly identify white voices, and 46.9% could identify Asian voices (Kushins, 2014). Another study that asked subjects to identify race from acoustic cues found that listeners could identify a speaker’s race at a rate of 60% correctness, which displayed less assured, yet still affirmative findings than Kushins’ study (Walton et. al., 1994). On a larger scale level, this research is important because it reflects the extent of the evolved and socialized abilities humans possess to identify in-group members, a necessary skill to build cultural comradery. Further studies about this trait even demonstrate that even on a neurological level, we categorize in-groups that we belong to in a different part of our brains than those we consider “other” and even react differently to their behavior, more easily forging bonds with our in-group members (Molenberghs, 2013). These findings encouraged me to investigate how adept we are at making such connections. Do we need to look at someone or converse with someone in order to classify and welcome them into our ingroup? Or has our radar for people similar to us become so sensitive that we can simply recognize people that we consider our own by the sound of a clue as minimal as their voice? With this promising previous research in mind, I sought to take this research a step further by identifying if a participant’s own was related to their proficiency in correctly identifying the ethnicity of speakers. I hypothesized that listeners that were of a speaker’s ethnicity, or more familiar with a speaker’s ethnicity, would correctly identify the speaker’s ethnicity more often than listeners that were of a different ethnicity. Methods In order to investigate the extent to which individuals can accurately determine a person’s ethnic group simply by listening to their voice, I created a Google Form survey to collect data about my peers’ ability to do just this. The notion behind my investigation requires ethnically diverse data, so I intentionally sought out participants from an array of ethnic backgrounds. Ultimately, my dataset consisted of 20 responses from participants of two genders identifying themselves as a member of one of five different ethnic groups: Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Middle Eastern, and White or Caucasian. There were at least two participants from each of the aforementioned ethnic groups. Unfortunately, no participants identified as American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander, which was the sixth ethnic group featured in the study. The survey began by asking participants to fill out a few questions about their demographic information, then asked participants to select which of these six aforementioned ethnic groups they felt most familiar with, both personally and through media. After this, participants listened to a set of six sound bites and then were asked to select which of the six ethnic groups (American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Other Pacific Islander, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Middle Eastern, and White or Caucasian) they believed each speaker from the sound bite belonged to. See below for a visual representation of how this type of question appeared: Figure 1: Sample survey sound bite and corresponding question These sound bites were taken from videos on the Youtube channel called Jubilee. Although some of the sound bites featured two people speaking, data was only inspected for one of the two voices, although participants guessed the ethnicity of all speakers whose voices they heard. Each of the sound bites that the data focused on featured a speaker from a different ethnic group, although participants did not know this. You can listen to these sound bites, and even quiz yourself, here: After collecting this data, I analyzed these findings in the following three ways: Results Before diving into the results, I feel it appropriate to make a few disclosures about the data that was collected throughout this study. First, the voices depicted in the sound bites in the study by no means represent the way that all people of their ethnicity speak. Additionally, because the study only contained twenty participants, the sample size is not large enough for the data to be truly representative of the general population, especially because there were only a couple of people in some of the ethnicity groups, such as the Hispanic or Latino group, with two. Here is a demographic breakdown of the participants by gender and by ethnicity: Analysis #1: Overall Accuracy Here, my findings for my first angle of analysis demonstrate that on average, 43.3% of participants can accurately identify a speaker’s race blindly. Participants guessed the Asian and White speakers the most accurately (85%), and the Middle Eastern speaker the least accurately (5%). In each graph, the green slice indicates correct responses. Further breakdowns for each sound bite are below: Analysis #2: Accuracy by Ethnicity Analysis #3: Accuracy by Participants Familiar with Featured Ethnicity Discussion Ultimately, the findings from my research provides evidence for humans’ ability to recognize a person’s ethnicity using their voice alone. Given that there were six ethnicities to choose from, we can assume that chance would give us a 1 in 6, or roughly 17% rate of predicting the ethnicity of a given voice correctly at random, however participants correctly identified the voice of a given speaker at a rate higher than 17% on four out of six occasions, according to the first angle of my analysis. The second set of results reveal that 60% of groups of participants by ethnicity correctly identified voices of fellow members of their in group at a more successful rate then participants not part of their ethnic group. This finding reflects that people are more adept at recognizing a speech style that they are biologically, and likely socially, related to. References Kushins, E.R. (2014). Sounding Like Your Race in the Employment Process: An Experiment on Speaker Voice, Race Identification, and Stereotyping. Race Soc Probl 6, 237–248. Molenberghs, P. (2013). The neuroscience of in-group bias. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(8),1530-1536. Walton, J. H., & Orlikoff, R. F. (1994). Speaker race identification from acoustic cues in the vocal signal. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 37(4), 738–745.

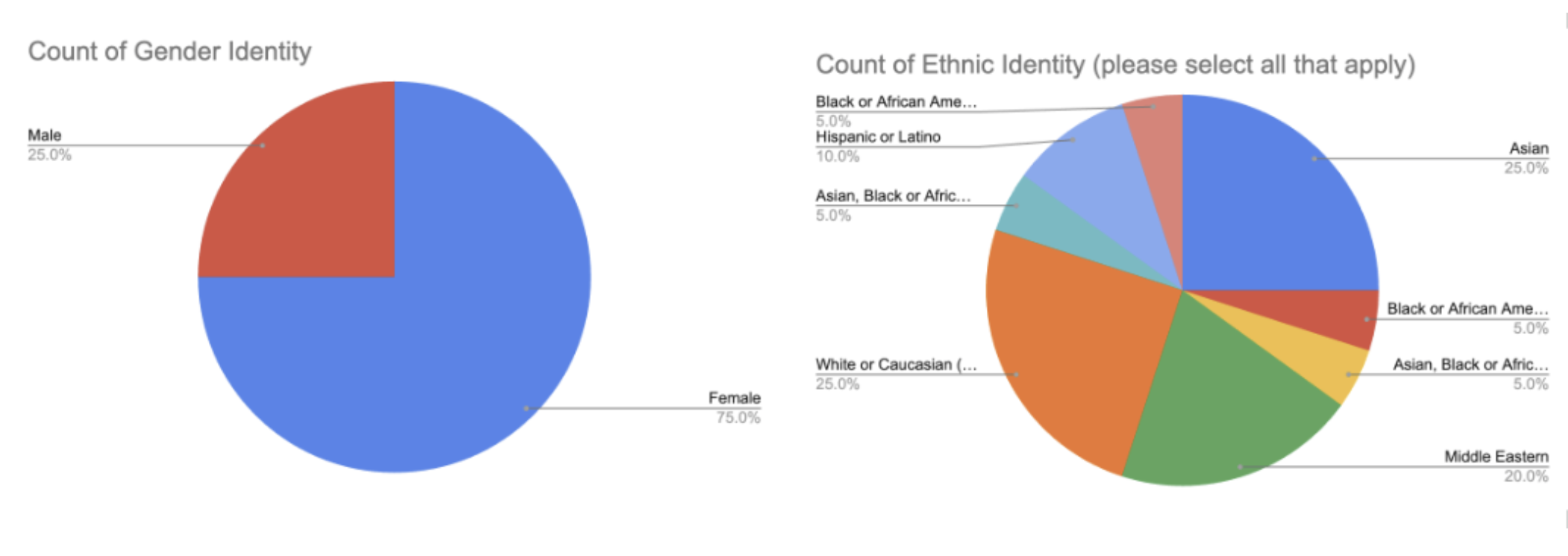

Figure 2: Participant demographic information (n=20))

Figure 3: Breakdown of all participant guesses for each sound bite

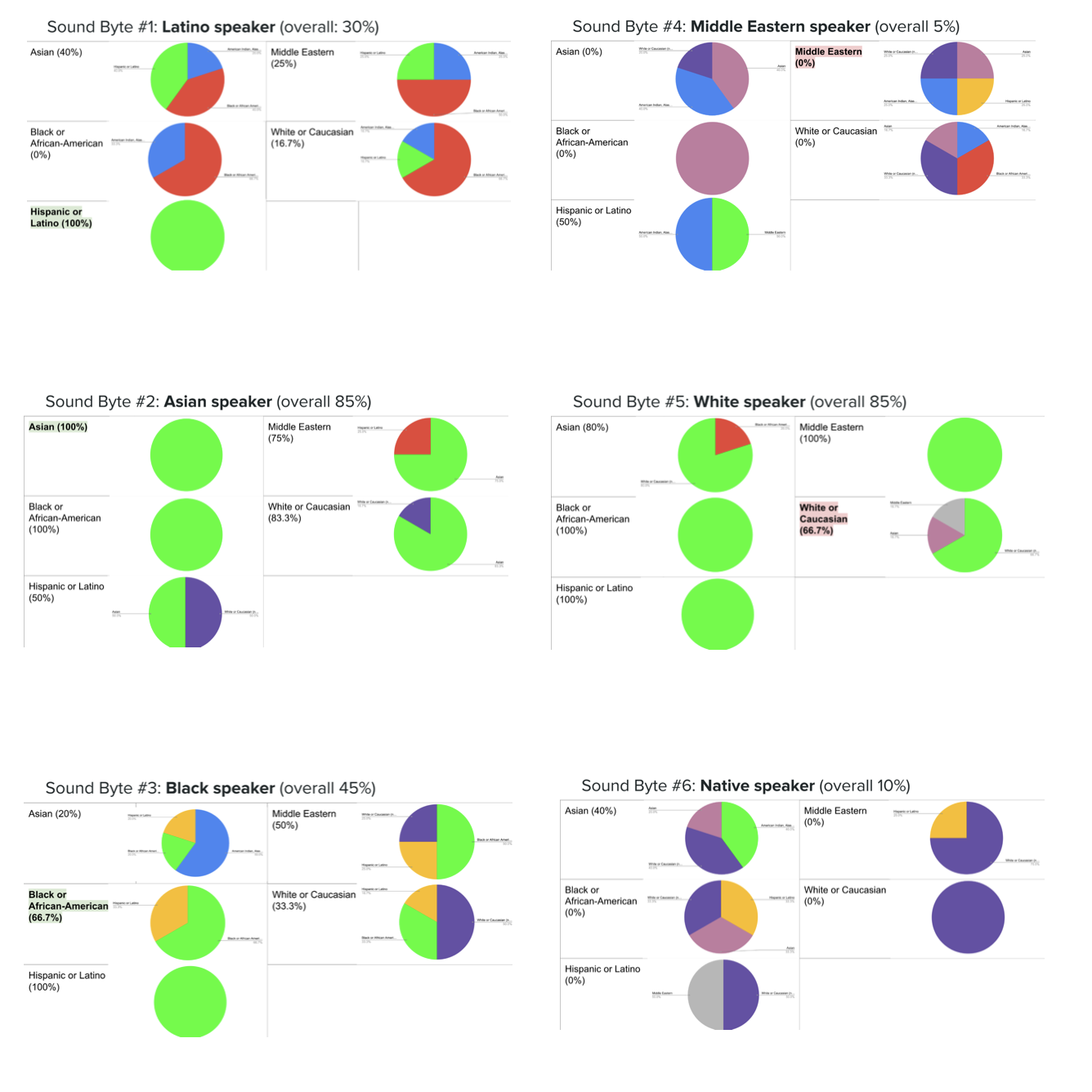

The findings for my second angle of analysis suggest that people may not necessarily have an overwhelmingly successful rate of identifying ethnicity purely from voice, but people who share an ethnicity with the voice they are hearing are more likely to identify ethnicity correctly. These results reflected that for 3 out of 5 surveyed ethnic groups, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, and Black or African-American, their average rate of successfully identifying the speaker’s voice was higher than the average rate across all ethnic groups. Interestingly, in the case of soundbite number three, which featured the Black speaker, the Hispanic and Latino group actually had a higher accuracy rate (100%) over the Black or African-American group (66.7%), although the group of Black participants still were more accurate than the overall average across all ethnicities. In the case of sound bite #4, featuring the Middle Eastern speaker, the data reflects that only one participant out of all, a Hispanic participant, correctly guessed the ethnicity of this speaker. In the case of sound bite #5, featuring the white speaker, the group of white participants actually scored lowest of the five ethnicities.

Figure 4: The graphs of each sound bite, broken down by participant ethnicity. A green highlight of the label of ethnicity means the percent correct for that ethnicity group is higher than the average percent correct across all responses, and a red highlight means the percent correct is lower than the average percent correct.

For three of the six ethnicities, Native, Asian, and Hispanic or Latino, those who identified themselves as familiar with a given ethnicity averaged a higher success rate than the average success rate for all participants. Additionally, please note that for the Native graph, there was only one respondent who indicated that they were familiar with that ethnicity.

Figure 5: Each graph displays responses of participants who identified themselves as being familiar with the given ethnicity featured in its respective sound bite. A green highlight represents the percent correct being higher than the average percent correct, and a red highlight represents the percent correct being lower than the average percent correct.

The third set of results reveal that 50% of the time people who classified themselves as being familiar with a particular identity were more accurate at identifying that particular identity over other identities that they were not familiar with. Although the first two results were in line with my hypothesis, this result is not, as I had hypothesized that being closer to an ethnicity would make a person more adept at recognizing its members. This shortcoming may either reflect that being familiar with another identity does not necessarily mean that you are better at distinguishing it, as being biologically related does, or it may reflect that people simply are not reliable judges of how familiar they are with a certain ethnic group.

Together, these findings reflect that there exist evolved mechanisms that help humans identify demographic information, such as ethnicity, about a new person using very minimal stimuli, such as just their voice. This result speaks to the fact that our ancestors’ survival relied heavily on knowing who to trust and associate with, and remnants of this trait still live within us today. Although the third angle of analysis was inconclusive, the first two angles of analysis, all participant data together versus participant data sorted by ethnic group, reveals an evident difference in in-group members recognizing fellow in-group members easier than a non in-group member.