Brian Cifuentes, Nicholas Guymon, Jafarri Nocentelli, Amanda T.

In this study, we investigate how native speakers of Puerto Rican, Guatemalan, and Mexican dialects of Spanish use /s/ debuccalization, a phonological process which targets /s/ in the coda position and yields either [h] or [∅] through complete deletion, to signal informal speech in Los Angeles. By examining the national origin, age, gender, linguistic background, and education of these three consultants who currently reside in Los Angeles but hail from elsewhere; the phonological characteristics of their native dialects; and the characteristics and use of Español Vernáculo de Los Ángeles (EVLA), the preeminent variety of Spanish spoken in Los Angeles, we identify /s/ debuccalization as a significant sociolinguistic marker across formal and informal registers. Indeed, we argue that the (non-)application of /s/ debuccalization across formal and informal registers reflects one facet of our speakers’ adaptation to the diglossic environment of Los Angeles, where the prestigious variety, EVLA, influences informal speech practices and how this phonological variation contributes to the construction of identity in multicultural urban settings.

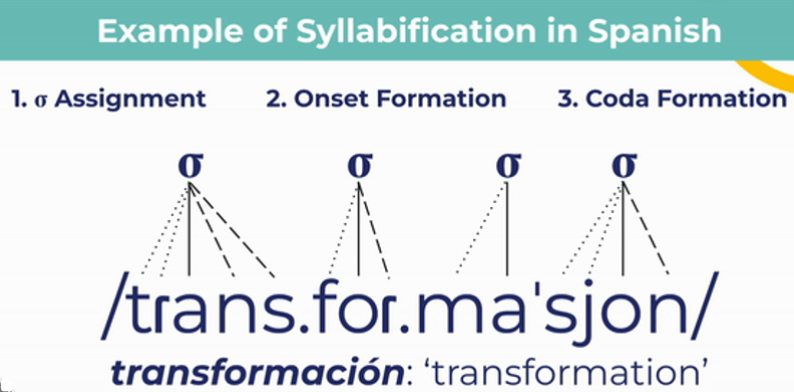

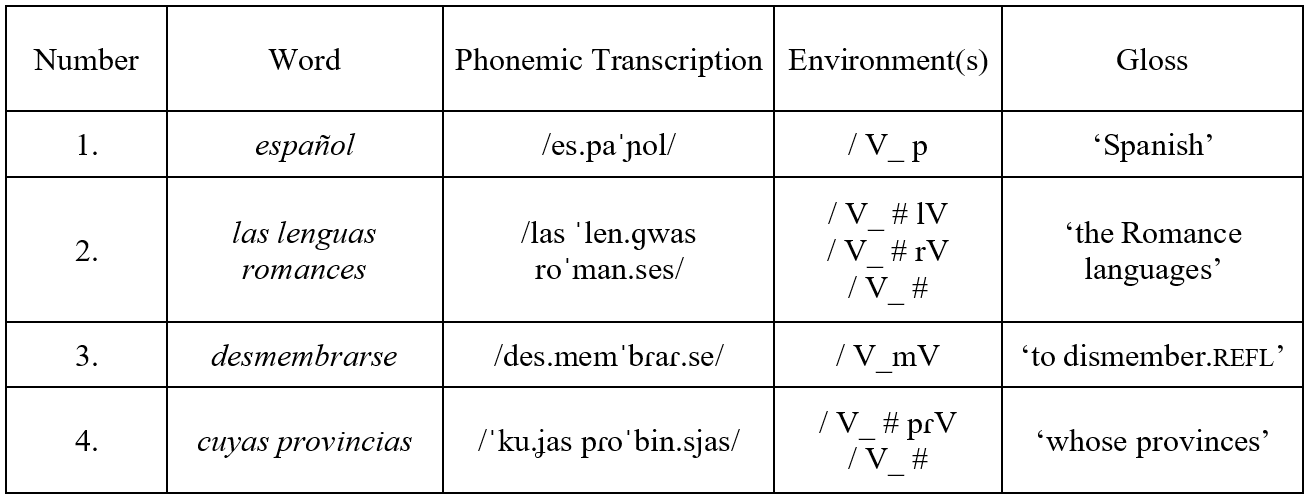

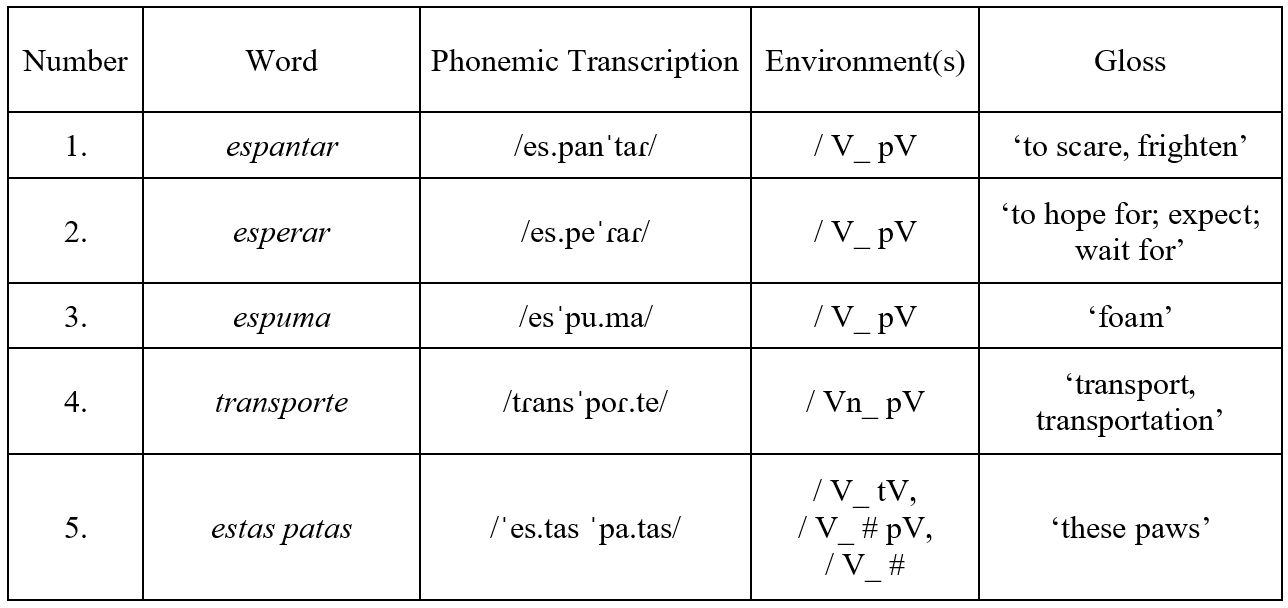

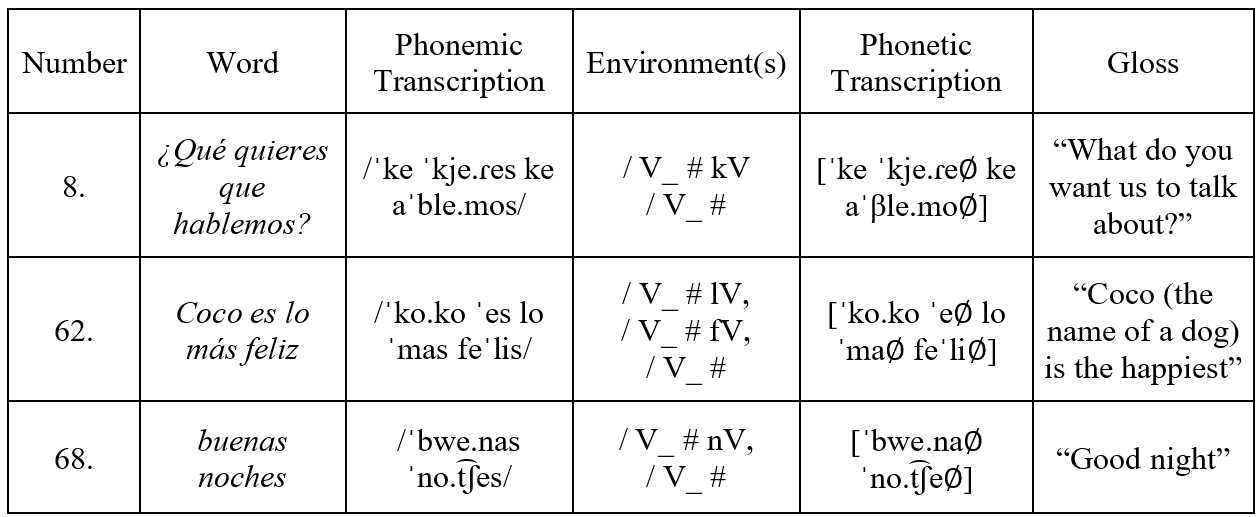

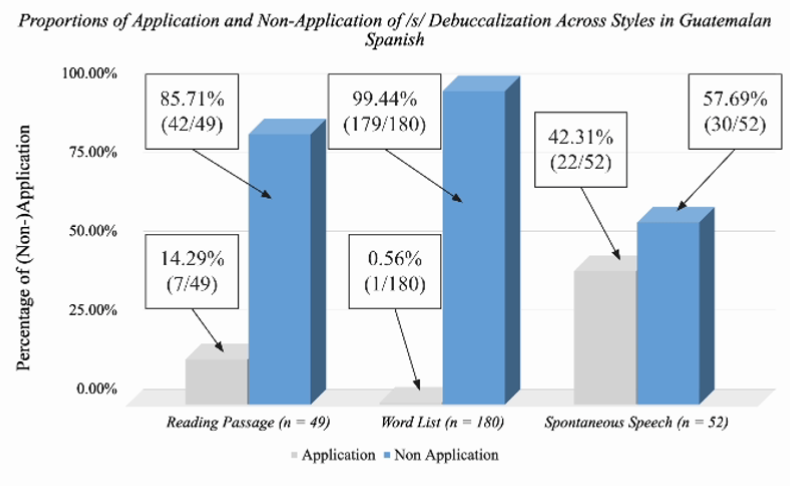

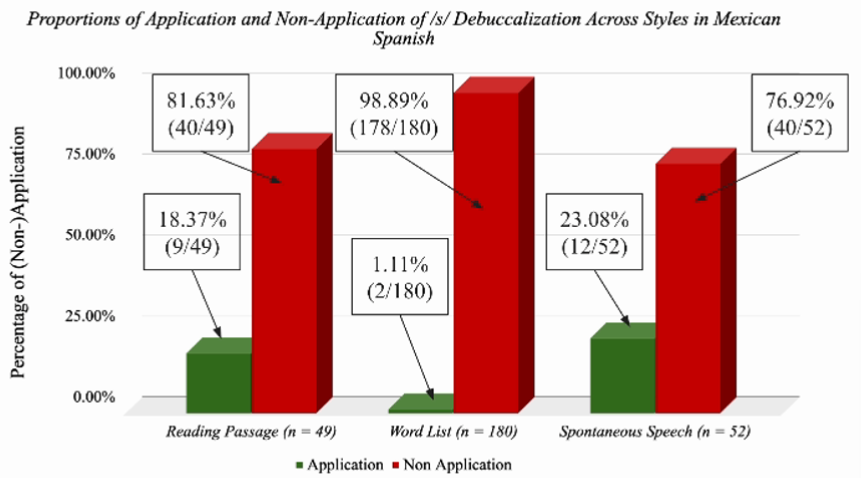

Introduction and Background In this article, we investigate how male and female native speakers of Puerto Rican, Guatemalan, and Mexican dialects of Spanish living in Los Angeles signal informal speech through a phonological process known as /s/ debuccalization, which targets instances of /s/ in coda positions and yields [h] or [∅] through complete deletion. By considering the national origin, age, gender, linguistic background, and education of our consultants, the phonological features of their native dialects, and the interaction between geographically removed Spanish dialects in Los Angeles, we aim to answer the following questions: What phonological features characterize Puerto Rican, Guatemalan, and Mexican Spanish vis-à-vis EVLA (Español Vernáculo de Los Angeles), the preeminent variety of Spanish spoken in Los Angeles? How can diglossia explain the distribution of phonological phenomena (e.g., /s/ debuccalization in Puerto Rican Spanish) observed in the informal speech of these dialects in Los Angeles? How do speakers create connections between their homeland and construct their identities through their native dialects in a context of linguistic isolation and geographic dislocation? In the speech of one of our consultants, a woman named Rosalie who currently resides in Los Angeles, for instance, we will examine the optionality of /s/ debuccalization, or /s/ aspiration, in Puerto Rican Spanish. We aim to answer the following questions: Can we predict in which environment(s) /s/ debuccalization occurs and what sociolinguistic variables affect the optionality of this rule itself? Is the (non-)application of this rule related to formality and prestige? How does Rosalie’s (non-)application of /s/ debuccalization index her membership to different speech communities of Spanish speakers? We hypothesize that in informal contexts with speakers of the same dialect or other dialects in which /s/ debuccalization occurs, our speakers will apply /s/ debuccalization. Conversely, in formal contexts with speakers of the same dialect and other dialects of Spanish where this feature may or may not be present, our speakers will not apply /s/ debuccalization. Methods In order to contrast the characteristics of the informal speech of Puerto Rican, Guatemalan, and Mexican dialects of Spanish with EVLA, it is necessary to describe the phonological features of each of our speakers’ dialects and those of EVLA, a “Spanish koiné in Los Angeles which has a distinct Mexican flavor spiced with those Spanglish features typical of the intimate contact with English: convergence, borrowings, calques, switches, and so forth” (Sánchez-Muñoz, 2007, pg. 74–75). Before we could describe the phonological features of our speakers’ dialects of Spanish, we gathered demographic, geographic, linguistic, and biographic information through a questionnaire which each of our speakers completed independently. Among these questions, we asked our consultants about their age, preferred gender identity, educational background, native language, daily usage of and literacy in Spanish, and their perceived proficiency in any other languages. Finally, we asked about our consultants’ birthplace, the cities/regions in which they grew up, the duration of their residence in those cities/regions, and the duration of their residence in Los Angeles, California. We have marked the locations where our consultants grew up and the location of Los Angeles in the following map: The geographical information helped us determine our consultants’ dialects of Spanish and the unique phonological phenomena which characterize these dialects themselves. In our consultants’ speech, we identified a common phonological process: /s/ debuccalization. Excursus on Syllable Structure Recalling that /s/ debuccalization is intimately linked to syllabic structure, we provide a brief discussion of syllabic structure, syllabification, and relevant terminology used throughout our analysis, drawn from Hayes (2009, pp. 251–253). Roughly speaking, the syllables have three main anatomical components: a nucleus, onset, and coda. With these terms in mind, words can be syllabified according to the following principles: In Figure 2 below, we provide an illustrated example of the syllabification of the Spanish quadrisyllabic, or four-syllable, word transformación ‘transformation’ in phonemic transcription. In this example, there are two instances of /s/: one /s/ appears in the coda of the first syllable, and another appears in the onset of the final syllable. Indeed, the phonological process of /s/ debuccalization will affect the surface realization of only the first /s/ in the first syllable of the word, found in coda position. The second /s/, belonging to the onset of a syllable, will remain unaffected. /s/ Debuccalization and Spanish Varieties /s/ debuccalization has been famously studied in Puerto Rican Spanish (García et al., 2023; Lipski, 2008; Sánchez-Muñoz, 2017; Tomás, 1999). In Guatemalan and Mexican dialects, however, its occurrence is geographically restricted. /s/ debuccalization is not typically observed in Guatemalan Spanish, “only along the border with El Salvador, along the Pacific coast, and near the border with Belize is a slight weakening of preconsonantal /s/ to be found” (Lipski 2008, p. 184). A similar situation holds in many Mexican dialects of Spanish, but there is “significant reduction of final /s/ … [also found in] rural northwestern Mexico, including the state of Sonora” (p. 85). Conversely, speakers of EVLA, as Sánchez-Muñoz identifies, do not debuccalize /s/ to produce [h] or [∅] (pp. 74–76). If speakers of EVLA, therefore, lack a synchronic phonological process of /s/ debuccalization, this process in any of our consultants’ speech will have an important indexicality value to speakers of EVLA and other varieties where this feature does not occur. The application of /s/ debuccalization may not only index our consultants as non-locals, but it may also have other important sociolinguistic ramifications involving prestige, social interactions, and linguistic attitudes. Since EVLA is the preeminent variety of Spanish spoken in Los Angeles, we anticipate that the distribution of phonological phenomena, such as /s/ debuccalization, will be influenced by diglossia, with the high variety being EVLA and other dialects being low varieties. This categorization will allow us to compare the role of language prestige and other social factors in shaping informal speech patterns, shedding insight on how Spanish speakers from different national origins and linguistic backgrounds modify their speech to negotiate their social identities and community affiliations in a multicultural setting like Los Angeles. Project Design In order to collect quantitative data, we conducted a series of sociolinguistic interviews with our consultants, guided by methods outlined in Van Herk (2018, pp. 121–122). After gathering demographic and biographical information, we recorded our consultants as they read the first paragraphs of Menéndez Pidal’s Manual de gramática histórica española, a technical linguistics manual written in Spanish, and a Spanish word list of 87 items in which /s/ occurs in a variety of phonological environments. Finally, we recorded a live conversation between our consultants and another native speaker of the same dialect. In all of these materials, we gathered environments in which /s/ appeared in coda position, using each instance as a token of /s/ subject to /s/ debuccalization which we later compared across styles. In Menéndez Pidal’s text, we identified 49 instances of /s/ in coda position, with 180 in our curated word list. As we prepared for our elicitations, we provided the orthography, phonemic transcription, and gloss of each Spanish word, following Harris (1969). We supply two sample tables below: After our elicitations, we reviewed our recordings, created phonetic transcriptions of each Spanish word, and compared our tokens of /s/ to the (non-)application of /s/ debuccalization. Then, we established proportions and calculated the percentages of the (non-)application of /s/ debuccalization. Lastly, we compared these proportions across styles and dialects. We predicted that as our consultants read the passage and word list, knowing that we were recording, we would induce the observer’s paradox, and our consultants would engage in more self-monitoring, likely reducing the frequency of phonological phenomena which characterize informal speech (Labov, 1972, pp. 43; Llamas, 2007, p. 15). Results and Analysis Our study revealed distinct patterns of /s/ debuccalization among our Puerto Rican, Guatemalan, and Mexican consultants, demonstrating how this phonological process varies across different speech contexts and dialects. Rosalie, our Puerto Rican Spanish speaker, displayed a notable variation in the application of /s/ debuccalization depending on the speech context. In the reading passage, we observed a very low application rate of 1 out of 49 instances (2.04%). In our word list, we observed an even lower application rate of 1 out of 180 instances (0.56%). In spontaneous speech, however, Rosalie’s use of /s/ debuccalization sharply increased to 70 out of 81 instances (86.42%). Below are some representative examples of /s/ debuccalization recorded in Rosalie’s spontaneous speech: The significant contrast of the application of /s/ debuccalization across styles suggests that Puerto Rican speakers switch between formal and informal registers, with /s/ debuccalization being a key feature in informal speech. These findings are summarized in Figure 6 below: Otto, our Guatemalan Spanish speaker, exhibited moderate variation in the application of /s/ debuccalization. In the reading passage, his application rate was relatively low with only 7 out of 49 instances (14.29%). In the word list, his application rate was minimal with only 1 out of 180 instances (0.56%) observed. In spontaneous speech, his application rate rose to 22 out of 52 instances (42.31%). This variability suggests that while Guatemalan speakers may use /s/ debuccalization as a marker of informal speech, the extent of its use can vary significantly depending on the context. The moderate application in spontaneous speech suggests that this phonological process is associated with varying degrees of formality, but not to the extent witnessed in Puerto Rican speakers. These results are summarized in the bar graph below: Blanca, our Mexican Spanish speaker, showed a low application rate of /s/ debuccalization in the reading passage at 9 out of 49 instances (18.37%). Her application rate was very low in the word list at 2 out of 180 instances (1.11%) and remained relatively low in spontaneous speech at 12 out of 52 instances (23.08%). These findings suggest that /s/ debuccalization is present in her dialect of Mexican Spanish across different styles, but it is not nearly as pronounced of an indicator of informal speech as in Guatemalan or Puerto Rican Spanish. The consistent yet low application across all contexts indicates that this feature may not be subject to significant sociolinguistic variation for Mexican speakers in Los Angeles. Additional research, however, may prove or disprove this claim. These findings are illustrated in the following chart: Discussion and Conclusions Indeed, our results indicate that /s/ debuccalization is a linguistic marker (Watt, 2007, p. 6) and that its use appears to be correlated with style. In the Puerto Rican dialect of Spanish spoken by Rosalie, the correlation is the strongest. In the Guatemalan dialect of Spanish spoken by Otto, the correlation is less pronounced than in the Puerto Rican dialect we investigated. In the Mexican dialect of Spanish spoken by Blanca, the correlation is the weakest. Although a correlation exists between style and /s/ debuccalization across these dialects, it must be noted that correlation does not imply causation. In other words, it would be fallacious to claim that differences of formality between styles alone affect the (non-)application of /s/ debuccalization. Such a claim risks removing agency from speakers themselves. Within social interactions, a speaker’s consistent use or avoidance of geographically-specific features may signal a desire for particular associations which become salient depending on the sociolinguistic context. The use of these features is also mediated by the diglossic situation of Los Angeles, which affords varying levels of prestige to different Spanish varieties which come into contact in the city. For Puerto Rican speakers, for instance, /s/ debuccalization is a prominent feature in spontaneous speech, whereas for Guatemalan and Mexican speakers, its use is more variable and less pronounced. On the one hand, Rosalie, Otto, Blanca, and other Spanish-speaking LA residents, may adopt specific features of EVLA despite their own national origins and linguistic backgrounds because phonological processes such as /s/ debuccalization may index them as non-locals to speakers of EVLA and other varieties where /s/ debuccalization does not occur. On the other hand, the retention of dialectal features may be understood as a direct connection between speakers and their regions of origin where these features are found. These sociolinguistic phenomena may also be understood according to the SPEAKING framework (Hymes, 1974b) and Accommodation Theory (Giles & Coupland 1991). We must consider our own identities and backgrounds as participants in our sociolinguistic interviews and those of the people whom our consultants called as variables which have influenced our interactions themselves. Accommodation Theory complements the SPEAKING framework of Hymes (1974b) by explaining sociolinguistic interactions through processes of convergence and divergence. In the former, speakers and interlocutors adapt their communicative behaviors, and in the latter, speakers accentuate their speech and nonverbal differences (Sánchez-Muñoz, 2017, p. 77). Thus, it is likely that our speakers’ convergence and divergence involving /s/ debuccalization involves a linguistic awareness of dialectal variation which is mediated not only by the presence or absence of this feature in the phonologies of their interlocutor(s) but also by the prestige afforded to EVLA at the expense of their native varieties. Further Readings If any of the topics above interested you, we recommend looking at some of the following blog posts and videos on YouTube: References García, C., Walker, A., & Beaton, M. (2023). “Exploring the role of phonological environment in evaluating social meaning: the case of /s/ aspiration in Puerto Rican Spanish.” Languages, 8(3), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages8030186. Giles, H., & Coupland, N. (1991). Language: Contexts and Consequences. Brooks/Cole. Pacific. Grove, CA. Herk, G. V. (2018). What Is Sociolinguistics? (2nd ed.). Wiley Blackwell. Labov, W. (1972). “The social stratification of (r) in New York department stores.” In Labov, W. Sociolinguistic Patterns (pp. 43–54). University of Philadelphia Press. Philadelphia, PA. Llamas, C. (2007). “Field methods.” In C. Llamas, L. Mullany, & P. Stockwell (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Sociolinguistics (pp. 12–18). Routledge. Lipski, J. M. (2008). Varieties of Spanish in the United States. Georgetown University Press. Washington, D.C. Menéndez Pidal, R. (1958). Manual de gramática histórica española (10th ed.). Espasa-Calpe. Madrid. Sánchez-Muñoz, A. (2017). “Tempted by the words of another: Linguistic choices of Chicanas/os and other Latinas/os in Los Angeles.” In J. Rosales & V. Fonseca (Eds.), Spanish Perspectives on Chicano literature: Literary and Cultural Essays (pp. 71–81). Ohio State University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv3znwwz.9. Tomás, N. T., & de Ramírez, M. T. V. (1999). El español en Puerto Rico: contribución a la geografía lingüística hispanoamericana. La Editorial, UPR. Watt, D. (2007). “Variation and the variable.” In C. Llamas, L. Mullany, & P. Stockwell (Eds.), The Routledge Companion to Sociolinguistics (pp. 3–11). Routledge. Harris, J. W. (1969). Spanish Phonology. MIT Press, MA.