Language preferences and code-mixing among UCLA bilinguals in different social settings

Shiqi Liang, Leen Aljefri, Yingxue Du and Tianyi Shao

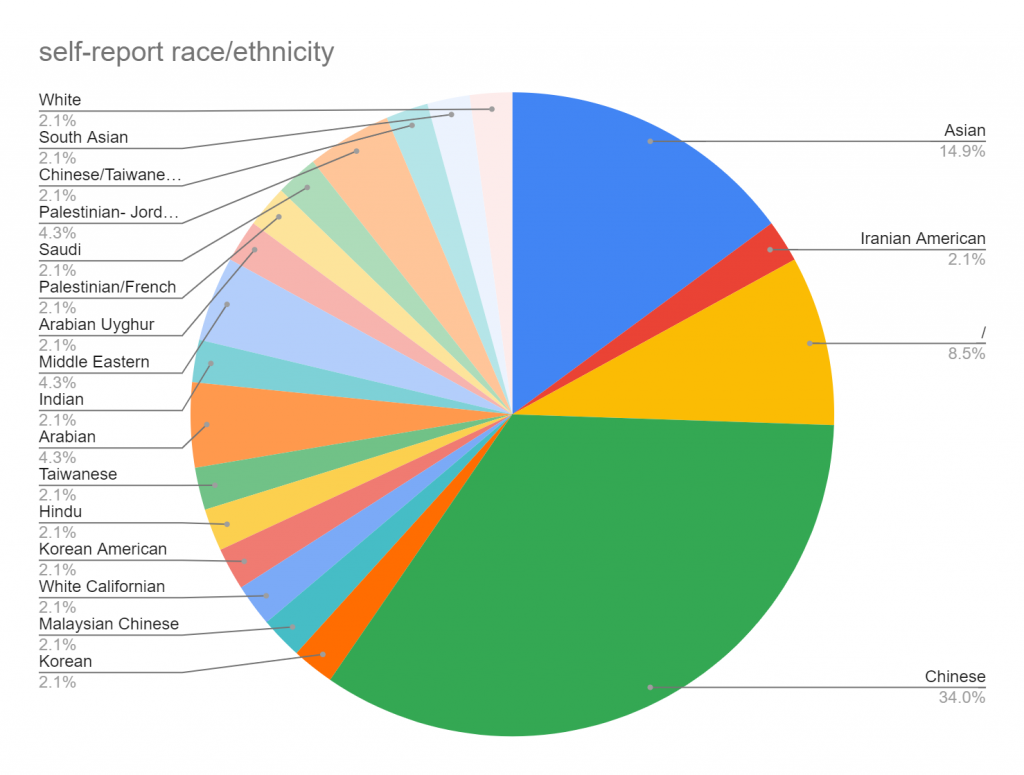

Here at UCLA, we have a diverse student body coming from many different backgrounds, which means we do have a sizable bilingual population on campus. Bilinguals and multilinguals often find themselves navigating through different social settings that require them to speak different languages. As bilingual speakers, switching between languages is quite common for us that it almost becomes a daily routine. However, when we really carefully think about that daily routine, there are so many questions we want to ask. Do we have a preference of one language compares to the other? Do our preferences vary? How do they vary? Do we mix languages? If so, how and why do we mix languages? Do bilinguals here at UCLA have a specific language preference when it comes to discussing fluid dynamics or gossiping about the latest juicy drama? Based on our study of 47 questionnaire responses collected from UCLA bilinguals and multilinguals, we arrive at the conclusion that among them, English is predominantly preferred in academic and professional related settings as well as social settings. At the same time, non-English languages are preferred in family settings and are present in social settings as well. We observed that code-mixing, the practice of mixing different languages together, is generally avoided, except when it is used as a tool for clarification.

Bilinguals experience potential conflicts between the two cultures behind the languages they speak. Language preference among bilinguals is related to the process of acculturation and socialization. Previous studies have identified the relationship between language preference and socialization, and literature addressing the relation can provide us with insights into the subject of interest. Song (2017) addresses the relationship between second language acquisition and socialization in “Second Language Learning as Mode-Switching” through the following idea: if social relations/context changes, then people employ a different linguistic and pragmatic mode to adapt to the new social expectation. Song adds that learning a second language requires the understanding of different speaking norms, linguistic values, and the rules of grammar. Language preference among bilinguals, therefore, can indicate the preference of one social norm to another to some extent. On the other hand, the fact that language preference among bilinguals is related to socialization is further addressed through a study conducted on infants and 9-month-old children (Valji & Poka, 2014), in which the infants show no preference for one language over the other and the 9-month-old children show preference in their native languages over the non-native language. As the social situations get more complicated when the bilinguals enter adulthood, the factors that might influence them to choose one language over the other are increasingly complicated and it is reasonable to articulate a relationship between social circumstances of a specific conversation and the language preference in that specific setting.

Observing the way multilinguals communicate with individuals in predominantly monolingual community is different than observing multilinguals in their own communities. Social and linguistic characteristics of multilinguals can be more noticeable when directly contrasted to monolinguals in the same community. As a first step to understanding what it means to be multilingual in a monolingual community, it is useful to look at a small bilingual population in such a community. The main focus of this project is to study the change in language preference according to situations and the frequency of code-mixing (practice of mixing different languages in one interaction) in bilinguals. In an effort to determine if a trend exists among the bilingual population here at UCLA when it comes to linguistic behavior, we conducted a case study and surveyed a group of 47 bilinguals at UCLA.

To better illustrate exchanges and preference in the use of language among bilinguals, here is an exchange between two English-Mandarin bilingual speakers talking about. The excerpts from this conversation is to present an example of how bilingual speakers interact with each other and how code-mixing happened during the conversation. The two bilingual speakers have conversations in their native language, and case study is to record and transcribe their conversation, and analyze the part that code mix happened. Throughout the whole conversation, code-mixing happened four times when participant B’s spoke. The four code-mixing can roughly be divided into two categories based on their cause, for clarification purposes and habit of word using.

A: 不是,我是说现在就你一个人在这个...... 空间啊? No, I mean right now are you just alone in that...... space? B: 现在?Right now? Right now? Right now?

This is where code-mixing first happened during the conversation, and the purpose of it is to clarify the meaning of the word “现(xian)在(zai)”, which means present time. However, the meaning is not clear enough, because that word can represent different length of present time, and that can make the whole sentence a different meaning. Here, the phrase “right now” appeared as a clarification, which is similar to the purpose of the next exchange.

A:我听说过,但我不清楚是治愈(Zhi Yu)的还是致郁(Zhi Yu)的? I’ve heard about that, but I am not quite sure if it’s a healing story or a gloomy story. B:是healing的那种,...... 结果两个人无意间卷进了road trip, 然后慢慢变好。 It’s the healing type, .... The two people happened to be on a road trip, and things are getting better.

In this exchange, individual B needs to use another language to clarify her sentence since the Mandarin for “healing” and “gloomy” has the same pronunciation, “zhi yu”. In the second case she chose to say “road trip” in English mostly because she want to evoke a special cultural reference not widely available in Chinese culture.

The main methodology of this research is centered around analyzing data gathered through an online questionnaire designed to generate simple yet precise responses from participants. Before answering the survey, participants would read a text that ask them to evaluate themselves and only proceed to answer the questions if they match all the requirements of what we consider to be bilingual/multilingual. There are 10 mandatory questions and 6 additional questions if the participant speaks more than 2 languages. Participants would first self-report the languages they speak (free response) then choose scenarios in which they would prefer to speak a certain language and the reasons behind that. In order to avoid half-completed questionnaires and encourage complete responses, questions that involves picking scenarios and reasons would be in forms of multiple choice instead of free response. However, if none of the options provided are satisfying, participants are free to enter their own response through the “other” option. The questionnaire itself was distributed among the researchers’ group of bilingual friends and an incentive (free boba) was provided to further encourage participation. You can find the full questionnaire here.

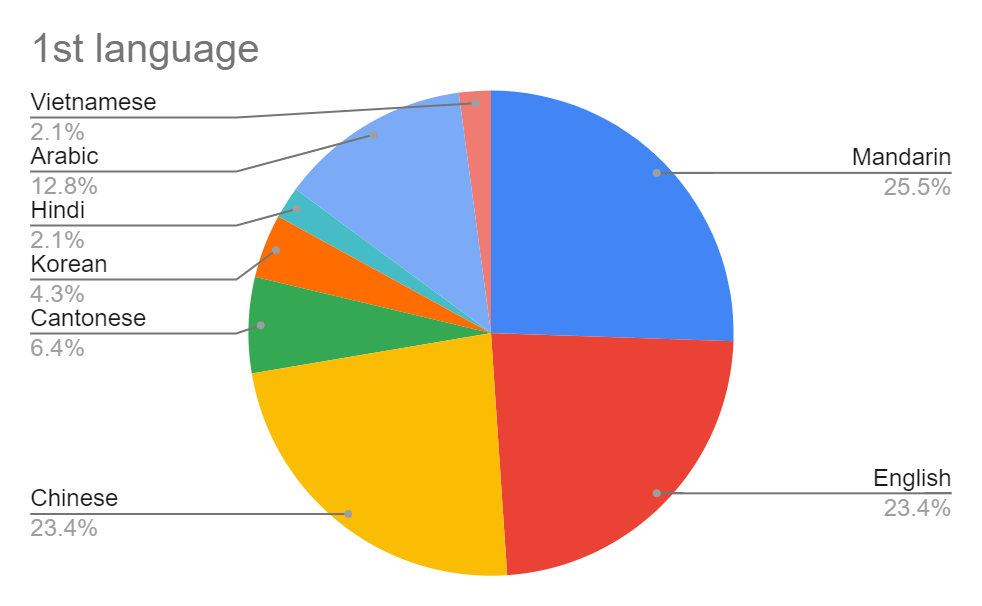

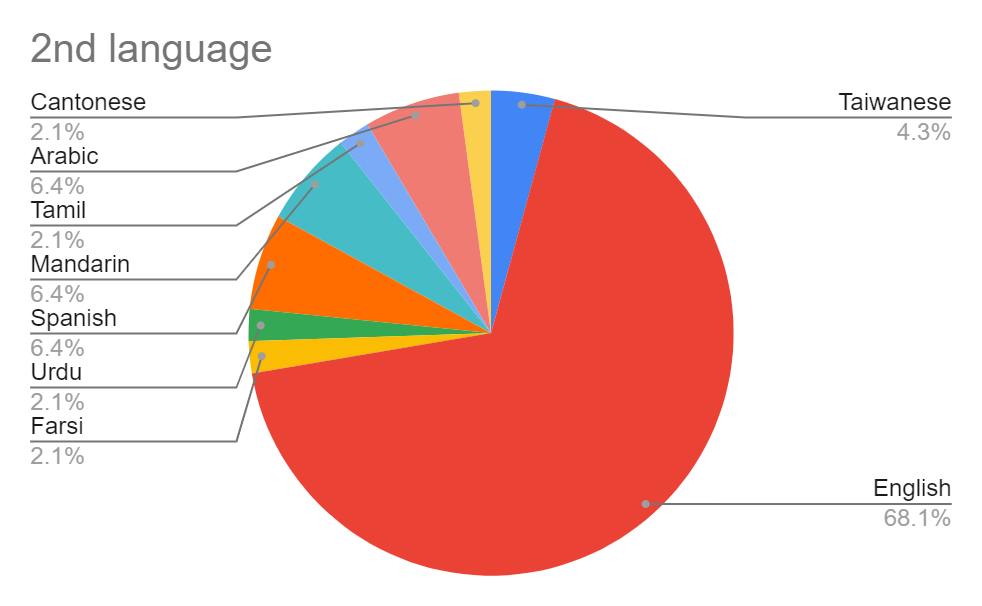

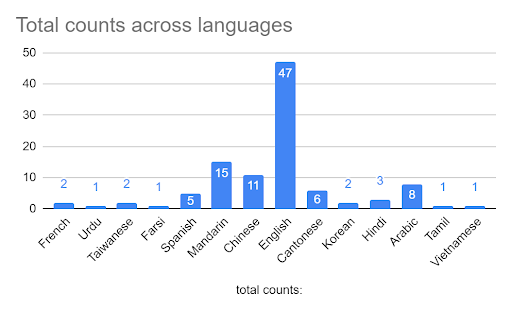

In the end 47 responses were gathered and subsequently analyzed. You can find our raw data and analysis here. Out of all those responses, all 47 of them indicated English as a language they speak, with the Chinese language family (Mandarin, Cantonese and Taiwanese) ranking the second most self-reported spoken language with 34 responses. But yet surprisingly, only 23.4% of participants consider English as their first language.

Unfortunately, as the sample size is relatively small and might not be an accurate representation of the entire student population at UCLA, the sample selection might be biased and the conclusions derived from the questionnaires might not be a representation of the entire multilingual student population. English, Mandarin and Arabic were selected because they have the most speakers and thus could relatively better represent themselves.

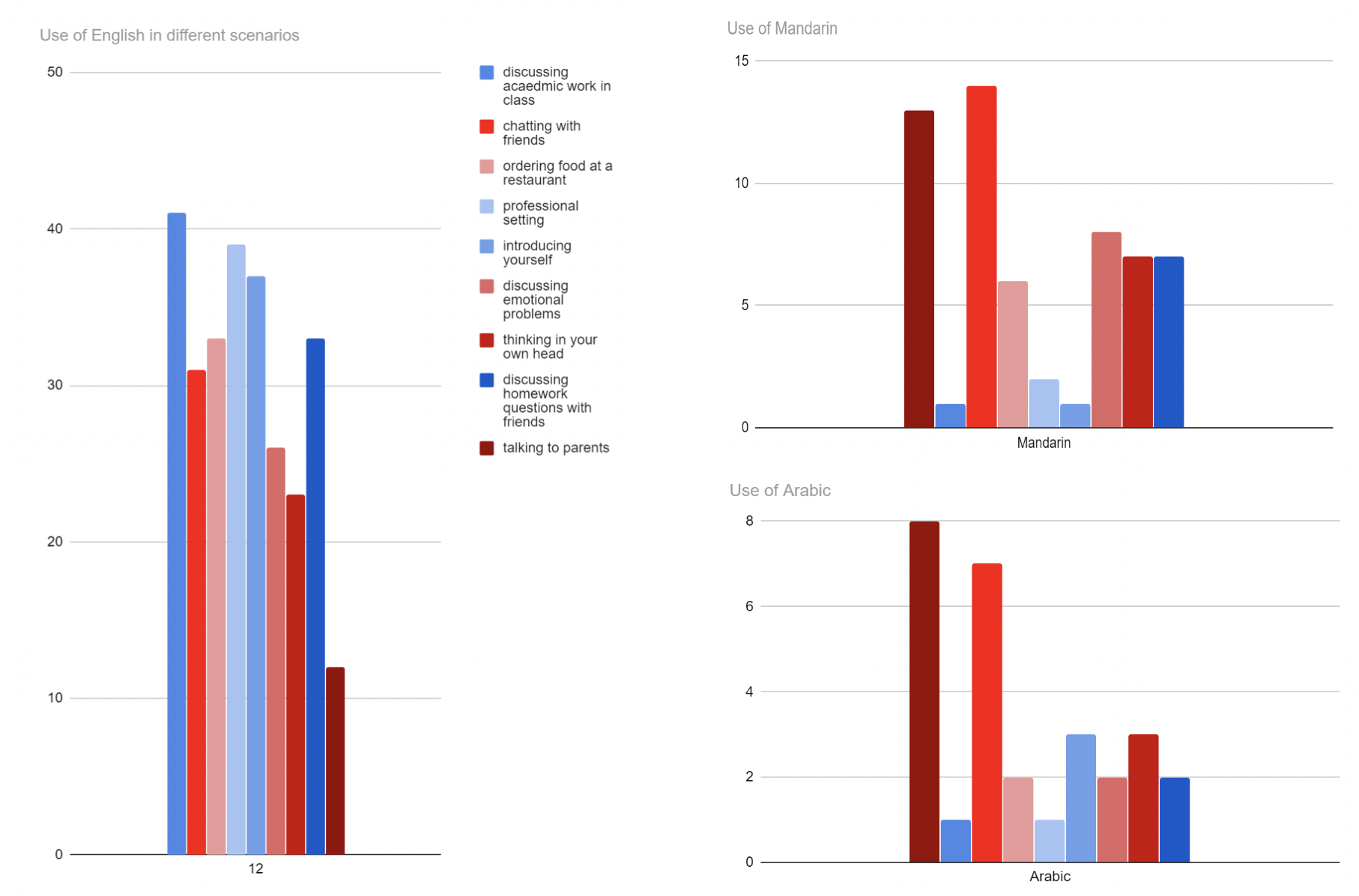

We could see that English is predominantly used in academic and professional setting (discussing academic work, discussing homework questions with friends, etc) and often used in social settings (talking to friends), yet less often used in family settings (talking to parents). Chinese and Arabic are less often used in academic and professional settings, but more prominent in social and family settings. This is rather predictable since UCLA is mostly a monolingual community and using a non-English language to discuss academic work is regarded as a social taboo. The prominence of non-English languages in family settings could be best explained by language preference in immigrant households in general. Children would mostly speak their parents’ native language in their own household due to new immigrants’ limited English proficiency.

Surprisingly, a lot of students also choose to discuss emotional issues in English. We predicted that since English is often associated with professional and academic settings, students might prefer a language that isn’t heavily associated with cold and rigid setting to discuss emotional issues. Our best explanation for this observed pattern is that some non-English languages, such as Mandarin and Arabic, are often associated with a more reserved culture. Thus, students may feel more comfortable speaking in English.

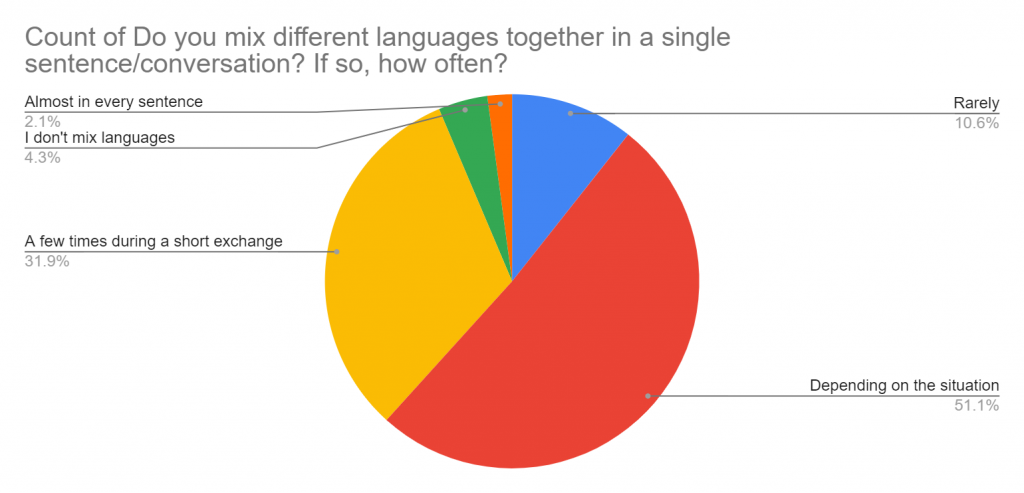

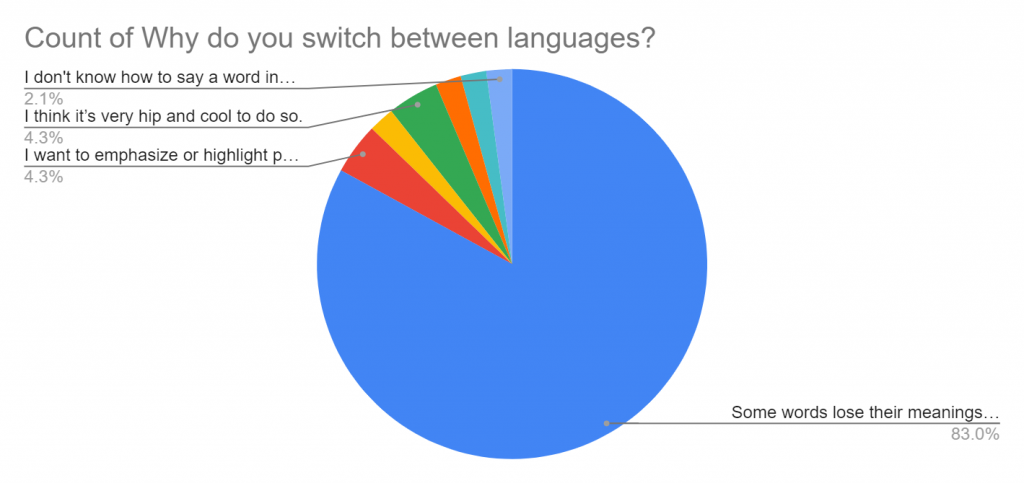

In terms of code-switching, most students answered “depends”. Only a few answered “almost in every sentence”. Data suggest that most students don’t prefer not to mix languages too often in their daily conversations. As for reasons for mixing language, almost everyone answered “in order to avoid misunderstanding or meanings lost in translation” or some variety of the same reason.

The complete reasons found in Chart 5.2 are listed below, from lowest to highest frequency:

-

- I don’t know how to say a word in Spanish

- I don’t know how to say a word in Chinese so I switch to English

- I don’t know how to say a word in Chinese so I switch to English

- I think it’s very hip and cool to do so.

- I don’t

- I want to highlight a part of my identity

- Some words lose their meanings when translated to another language, so to avoid misunderstanding I would mix the language together

As predicted, the majority of the responses confirmed the hypothesis that English would be the favored language in academic settings. Conversely, the other language by majority is likely to be spoken in more personal conversations such as speaking to family and friends.

While, UCLA is home to a large multilingual community, the general language of instruction is English. In a way, the level of English knowledge is controlled by the admission requirements. Consequently, that may play a role in justifying the preference for speaking English in academic settings. It is the university’s expectation of its affiliates, and so it is upheld by the student population regardless of multilingualism within the community itself.

References:

Song, S. (2017). Second Language Learning as Mode-Switching. Second Language Acquisition as a Mode-Switching Process, 75–100. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-52436-2_5

Valji, A., & Polka, L. (2004). Language preference in monolingual and bilingual infants. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 115(5), 2505–2505. doi: 10.1121/1.4783066

About the Authors

Shiqi (Susan) is a second-year statistics major at UCLA. She enjoys studying human geography and drawing in her free time.

Leen is a first-year engineering student from Saudi Arabia.

Christie is a senior majoring in theatre and has working experience of teaching bilingual children before. She enjoys listening to music and observing sunset glow and sunrise glow.

Tianyi is a senior majoring in Mathematics/economics at UCLA. She enjoys video games, music, and photography and she loves making observations about her life.