Gianelli Liguidliguid, Kyoo Sang Han, Victor Sohn

Korean dramas, otherwise known as “K-dramas,” have become easier to watch than ever before. With shows previously only being televised on South Korean TV stations, many people can now watch K-dramas on popular streaming platforms like Netflix and Hulu. Because of this, the popularity of K-dramas has spread everywhere, including in the U.S. With this rise in popularity, there has also been an increase in the amount of Konglish (Korean-English) being spoken in K-dramas. This study explores the number of code-switching instances from Korean to English in K-dramas targeted toward a specific age demographic and looks into code-switching characters. Our research focuses on eight K-dramas, four aired in the morning for older audiences, and four aired in the evening for younger audiences. We hypothesize that Korean-English code-switching will be more frequent in K-dramas targeted at a younger audience and that higher socioeconomic status will play a role in regarding who code-switches. Our data highlights which age demographic tends to code-switch more, focusing on inter-sentential and intra-sentential code-switches, and provides an overview of the types of characters that speak in both Korean and English.

Introduction & Background:

Korean culture has steadily been rising in popularity, and K-dramas are part of this universal fame, thanks to their easy accessibility through streaming services. Along with the recent success of Squid Game, many have watched K-dramas and might have noticed that English is frequently used in the Korean language. The bountiful use of English can be explained by the vast influence English has in modern Korea. For example, students are required to learn English starting from the age of 10, and it is also part of the official Korean SAT. The reputation of English in the current Korean society is untouchable, and Barratta (2014) describes that English is associated with modernity and power, creating a more modern identity for Koreans.

In this study, we wanted to analyze the frequency of code-switching in K-dramas and how it is affected by age and socioeconomic status. How would these factors affect how and when characters code-switch with each other? Since English is a sign of luxury and youth in Korea, this could affect the production of K-dramas. We hypothesized that Korean to English code-switching would be more frequent in K-dramas targeted at a younger audience. After evaluating our results, we concluded this is true but also noticed that more data might be needed for further detailed analysis.

Before diving any further, it is essential to explain what exactly code-switching is and how it differs from lexical borrowing. Lexical borrowing is a phenomenon whereby a loanword, at some point during the history of a language, entered its lexicon as a result of borrowing, transfer, and copying (Haspelmath, 2009). These words are part of the Korean language and are primarily loanwords that originate from English. On the other hand, code-switching is the alternating use of several languages by bilingual speakers (Muysken & Milroy, 1995). It is the practice of switching between two languages and is more frequent in conversation than in writing. Code-switching is used among speakers to convey meaning above and beyond the referential. There are three types of code-switching classified by linguists, but we decided to focus only on two: inter-sentential and intra-sentential. The first one happens at sentence boundaries, while the second one happens in the middle of a sentence.

Dramas are divided into two groups in Korea: morning and evening shows. Morning shows air sometime between 7:50 AM to 9:30 AM and is meant for an older audience, such as housewives or the elderly who have the time to watch TV early in the morning. It is rare for students or business people to watch morning shows since they are either studying or working. On the other hand, evening K-dramas air between 10:00 PM to 11:50 PM, usually after the daily news. These shows are targeted at a younger audience, such as students or other people who only have time to watch TV in the evening.

Our data was collected from a total of eight K-dramas. Four dramas targeting the younger audience were: Business Proposal, Sky Castle, Vincenzo, and You’re Beautiful. The other four targeting the older audience were: Always Springtime, Cheongdam-dong Scandal, Lady of the Storm, and Pink Lipstick. All of these shows were set in a contemporary setting (Modern day Seoul, Korea) and aired between 2010 and 2020.

Methods:

As our data collection method, we investigated code-switching occurrences in Korean dramas in an effort to find relations between the frequency of code-switching and the factors that influence code-switching. To conduct our research efficiently, we only analyzed the first episode of each drama that are equal in length (1 hour approximately, for a total of 480 minutes of data analyzed). Furthermore, we limited our subjects to only characters that are native Korean speakers that opted to code-switch to English and excluded any native English speakers or foreigners that had to code-switch out of necessity.

To collect our qualitative data, we analyzed the conversations where code-switching occurred and considered different factors that stimulated code-switching in context. As mentioned above, we hypothesized that socioeconomic status and age would influence our subjects hugely. We counted characters under 35 as younger speakers and over 35 as older speakers. To determine our subjects’ socioeconomic status and age, we searched their characters’ names on the “AsianWiki” site. There, it led us to find more about each character’s background. Another procedure we adopted was to analyze the instances of code-switching by applying the Leipzig Glossing Rules to dissect our data more precisely. This step assured us of avoiding any misinterpretation of any sort from switching from Korean to English and reinforced the clarity of our findings.

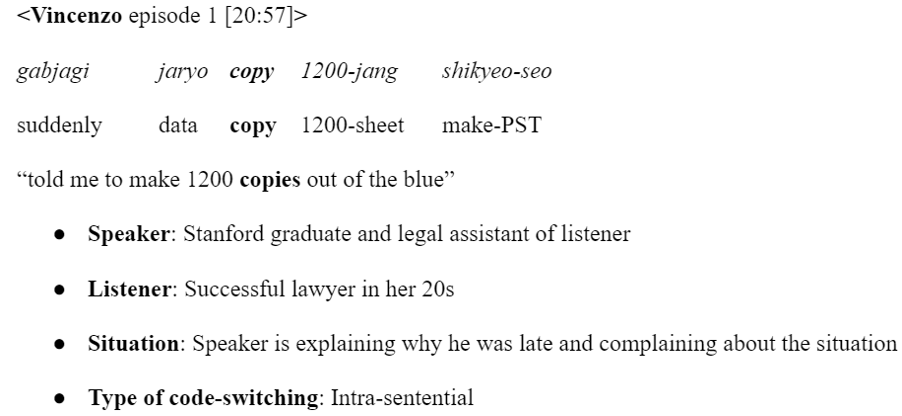

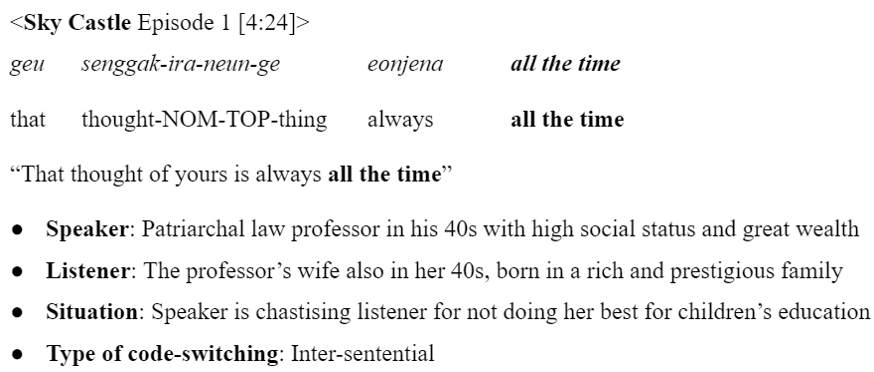

As our quantitative data collection method, we recorded every code-switching instance. We sorted out any cases that showed resemblance to code-switching but did not entirely satisfy the requirements such as lexical borrowing, copying, and transfer. This data was collected in order to see if any specific patterns of code-switching exist in these eight K-dramas, such as intrasentential code-switches vs. intersentential code switches. Any instance of code-switching was noted down, along with the character’s background, the situation they are in, the listener, and the type of code-switching. An example of how we collected data is seen in Figure 1 below.

Results & Analysis:

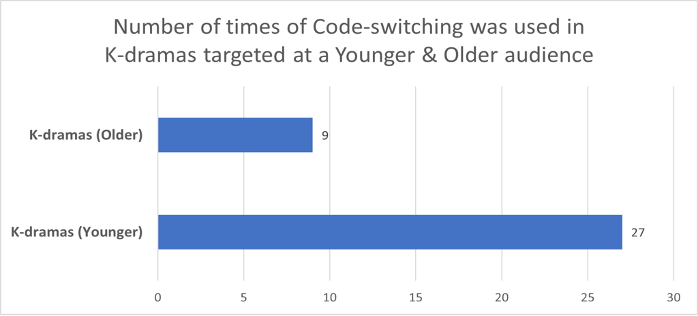

As we initially predicted, there were more instances of code-switching in K-dramas meant for a younger audience. Figure 2 below depicts the number of times code-switching was used in K-dramas comparing the shows intended for older and younger audiences.

As the figure reveals, code-switching was three times more frequent in K-dramas meant for a younger audience. Age is an important factor in code-switching, and K-dramas seem to imply more English-speaking characters if the show is meant for a more trendy and youthful audience.

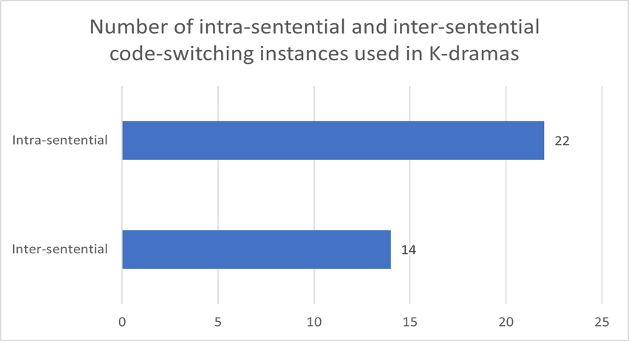

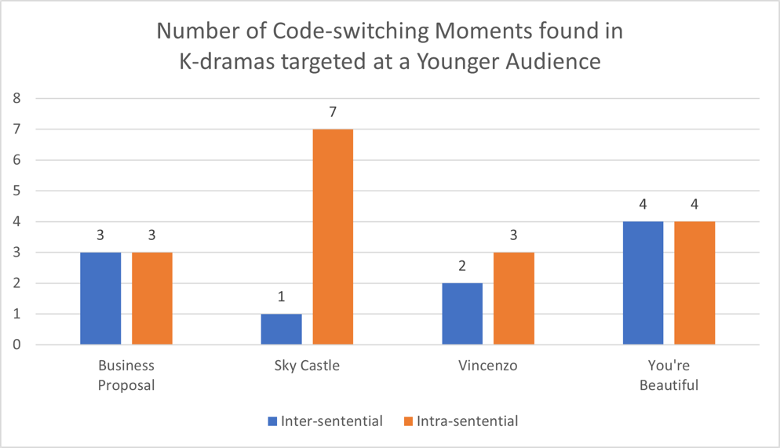

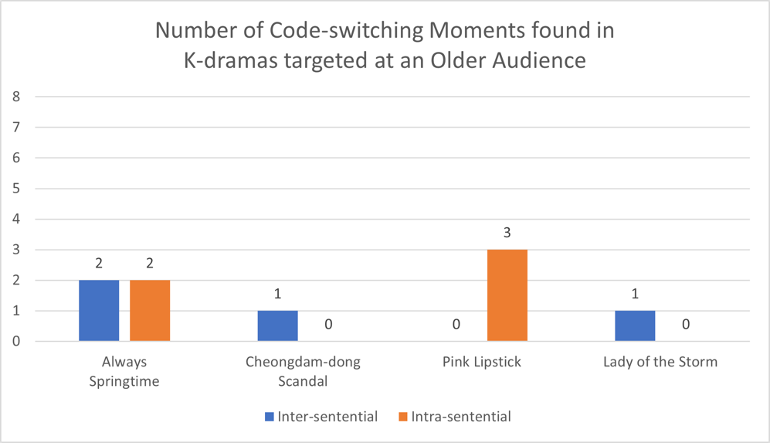

Only two types of code-switching were found in the K-dramas we analyzed: intra-sentential and inter-sentential switching. Figure 3 below shows the number of each code-switching moment found in the K-dramas we analyzed.

The data presents how both instances of code-switching were often used, but intra-sentential switching was 1.5 times more frequent than the other. It seems Korean speakers are fonder and more capable of code-switching in between sentences.

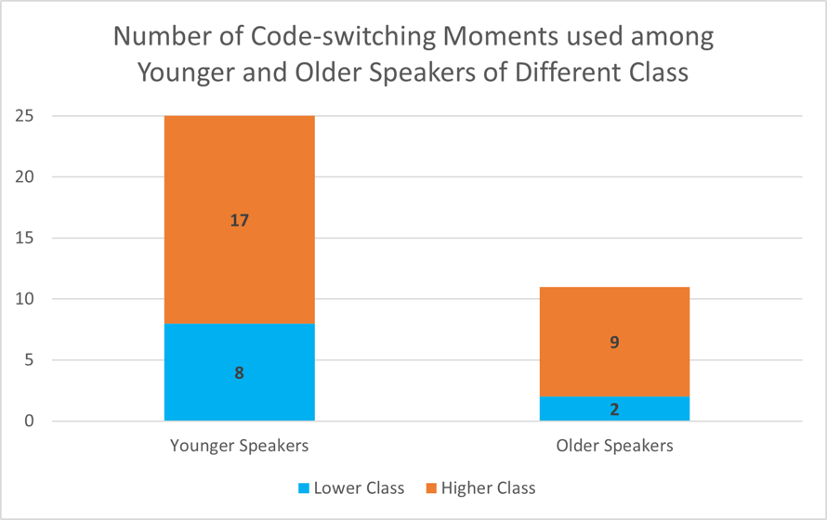

Also, characters of higher social status used code-switching more often than those of lower social status. Figure 4 below exhibits the number of code-switching instances based on age and socioeconomic status.

As the figure shows, younger speakers were more likely to use code-switching. Also, speakers of higher class would use code-switching more often than those of lower class. This data relates to how socioeconomic status is an essential factor influencing the frequency of code-switching found in K-dramas.

Figures 5 & 6 below show the code-switching moments found in K-dramas meant for younger and older audiences, respectively. It also divided which type of code-switching was used for each Korean TV show.

As shown in Figure 5, there was a relatively even number of inter-sentential and intra-sentential code switches in two of the four K-dramas targeted at a younger audience. However, in Sky Castle and Vincenzo, there was a larger amount of intra-sentential code switches than inter-sentential. Similarly, in Figure 6, there was a fairly even number of inter-sentential and intra-sentential code switches in two of the four K-dramas targeted at an older audience. However, in Pink Lipstick, there were zero inter-sentential code switches but three intra-sentential code switches. In Cheongdam-dong Scandal, there were no instances of intra-sentential code switches, but there was one instance of an inter-sentential code switch.

Considering the differences in word order between Korean Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) and English Subject-Verb-Object (SVO), the instances of code-switching between the two languages found in the data oftentimes served as emphases and iterations of the main points rather than facilitating communication. In many cases, the characters who used code-switching had the word order jumbled between Korean and English and formed redundant and garbled phrases. This phenomenon can also be attributed to the absence of articles in many Korean phrases. Unlike English, the Korean language does not require articles in every sentence structure. When the speakers switched from Korean to English, English articles were omitted in many cases.

As shown in Figure 7, the speaker used “always” in Korean and “all the time” in English to emphasize his point. Both “always” and “all the time” can be used interchangeably and mutually mean the same in this context to express his frustration. Hence, the instance of code-switching in Figure 7 can be considered redundant and impractical. Many other instances of code-switching occurrences were reiterations of the same phrase or expression said in Korean before or after within the sentence boundaries. Additionally, in K-dramas for an older audience, it was all younger speakers that used code-switching, except for one instance. This unique example was found in Always Springtime, where an older speaker repeats the word “family” twice, once in Korean and once in English, to emphasize his point comically.

Jo Yoo Jung Scenes (Part 02) || A Business Proposal

Lastly, we analyzed many different characters and found that the most frequently used code-switching phrase was “Oh My God,” which was found in a total of four K-dramas: Always Springtime, Business Proposal, Pink Lipstick, and Vincenzo. This phrase was usually said to add comedic effect to the conversation. One example can be seen here in one of the K-dramas, Business Proposal, with the character Jo Yoo Jung. She is seen as a high-status individual as she is the director of Marine Beauty, a (fictional) famous company in South Korea. At the beginning of this scene, she can be seen walking in and saying hello to the people who work for her. She starts speaking in Konglish, directing everyone to “go have some coffee” in English. The people she is talking to do not respond back in English. When Jo Yoo Jung turns around and notices that she is wearing a very similar outfit to another main character in Business Proposal, Jin Young-Seo, she yells, “Oh my god!” in fright.

In this particular scene, Jo Yoo Jung attempts to boast and advertise her English knowledge to characters of lower status than her. She is a high-class younger character who uses code-switching to raise her status and add authority to a message. This moment relates to how English is used to mark dominance and emphasize modernity. She is also aware that the people around her are of a lower class, so she might be attempting to make them feel excluded and point out their lack of English education. Jo Yoo Jung continues to code-switch after encountering another high-class speaker, knowing that she is capable of understanding her English phrases.

Discussion and conclusions:

We can see that higher class speakers were prone to code-switching, regardless of their age. When lower class speakers code-switch, it was primarily used for comedic relief, exaggeration, or imitation of a higher-class speaker. Also, when code-switching happened, it often occurred between the same age group: young & young or old & old. It rarely happens between different age groups. Additionally, the use of code-switching would often portray the character’s personality. For example, in the K-drama You’re Beautiful, an older speaker would use code-switching to express his quirky and upbeat personality to the audience.

We also noticed that higher class speakers use English to establish authority and dominance over the listener. On the other hand, lower class speakers would use code-switching because they want to fit in and raise their social status by using English. Younger speakers code-switched with each other to mark their group identity of youth and trendiness. Overall, it seems that English acts as a symbol of youth, modernity, and authority in the current Korean society.

However, our study also had some limitations. First, only a small number of K-dramas were analyzed, so the data is quite limited. Only the first episodes were evaluated, so we are missing several code-switching moments throughout the whole series. Also, it was difficult finding K-dramas meant for an older audience. K-dramas for a younger audience could easily be found on streaming platforms, but this was not the case for the other K-dramas. They would only be available in Korea and were hard to find on the internet. The difficulty of finding K-dramas for an older audience might have affected the small size of our data. Additionally, more accurate and neutral results might have been possible if the genres of the selected K-dramas were unified. Instead of having four to five different genres, having just one genre (ex: slice-of-life) could have led to more proper outcomes.

To further expand our research, we could look into code-switching moments happening in other Korean media sources. For example, more speech patterns could be analyzed in different forms of media such as movies, reality shows, etc. Also, we could analyze code-switching frequency in different time periods to observe how English was used in the Korean language several decades ago. For example, a K-drama from the 1980s might have less English usage and not have any code-switching instances at all. However, even with different analyses, we can observe that English has become a symbol and gained dominance in Korean society, influencing the language itself.

References:

Baratta, A. (2014). The use of English in Korean TV drama to signal a modern identity: Switches from Korean to English within Korean TV dramas signal an identity of modernity and power. English Today, 30(3), 54-60. doi:10.1017/S0266078414000297

Eversteijn, N. (2011). All at once: Language choice and codeswitching by Turkish- Dutch teenagers. PhD thesis. Tilburg, the Netherlands: Tilburg University.

David, M. Tien, W. Meng, Y. & Hui, G. (2009) Language choice and code switching of the elderly and the youth. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. DOI:10.1515/IJSL.2009.044

Fauziyah, Wulidatil. “An Analysis of Code Switching Used by Captain Yoo in Korean Drama Descendant of the Sun.” Etheses of Maulana Malik Ibrahim State Islamic University, 15 Dec. 2017, http://etheses.uin-malang.ac.id/11890/.

Jamie Shinhee Lee. (2014). English on Korean television. World Englishes, 33(1), 33–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12052

Jamie Shinhee Lee. (2006). Linguistic Constructions of Modernity: English Mixing in Korean Television Commercials. Language in Society, 35(1), 59–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/ 4169478

Mahootian, Shahrzad (2020). Bilingualism. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, London & New York.

Willoughby, Zoe, et al. “Bilingualism in TV: When and Why Does Code-Switching Happen?” Languaged Life, 20 Dec. 2019, https://languagedlife.humspace.ucla.edu/sociolinguistics/ bilingualism-in-tv-when-and-why-does-code-switching-happen/.