Sarah Bassiry (Sky), Anna Harutyunyan, Akina Nishi, Jasmine Shao

Diaspora communities and heritage language speakers are a very unique population when it comes to language and bilingualism. Heritage speakers vary greatly in their language skills, language background, and environment. As heritage speakers are generally exposed to their heritage language only at home or in other limited contexts such as a cultural community group, this study investigated to see if social media may also be a context of heritage language exposure for some heritage speakers. If so, this study investigates the role social media might play in language competence. Four Eastern Armenian and four Mandarin heritage speakers attending UCLA and one native speaker in each language, were participants in this study. The participants were given a language background survey, a grammaticality judgment test, and an elicitation task judged by a dominant native speaker using a Likert scale. Initially, we expected to see a positive correlation between social media usage in the heritage language and the participants’ heritage language skills. However, the results did not provide sufficient evidence to support this hypothesis. Thus, further testing with a larger sample size is recommended to further investigate whether or not there might be a correlation.

Introduction and Background

The concept of bilingualism is interesting to discuss in the context of heritage speaker populations, as these groups include speakers of a vast variety of language competence. Heritage language speakers ‘may or may not be frequent users of the language or exceptionally proficient in the language” (Mahootian, 2000). Many heritage speakers are also receptive bilinguals, which Nakamura (2019) notes, “does not imply zero production of the weaker language but highly limited language use in interaction.” These speakers usually have strong listening and comprehension skills but weaker production skills in their heritage language.

This study sets out to determine if there is a correlation between heritage speakers’ social media consumption in their heritage language and their competence in that language. A prior study on bilinguals and newspaper consumption conducted by Moring (2011) et al., found media to be an instrumental resource in maintaining language competence. Flewitt and Zhao (2020) also conducted a study investigating the relationship between heritage speakers and social media usage. In their study, they observed two adolescent Mandarin Chinese heritage speakers and their usage of WeChat to connect with relatives in the heritage language. They found that WeChat acted as a “springboard to include multilingual practices” and facilitated a motivating environment of supportive feedback from interlocutors for their language to grow.

Given the previous research in the field, we hypothesized that our study would show that more frequent social media consumption in the heritage language will be correlated with a higher degree of language competence. Previous studies have noted that in the case of young children, engagement with social media often involves “several types of learning and socialization occurring all at once” (Zhao, 2019). In this study, we aimed to observe the role social media activity plays in the heritage language competence of young adults at UCLA.

Methods

The population this study investigated was heritage speakers of either Mandarin or Eastern Armenian who attend UCLA, testing 4 participants for each language. This project utilized survey methods, grammaticality judgment tasks, and elicitation tasks to investigate the research questions.

Our general survey asked participants basic questions regarding demographics, social media usage in the heritage language, and information regarding details of heritage language background and exposure. Two separate grammaticality judgment tests with 20 questions each were created by bilingual speakers of each language from the research team. The Eastern Armenian task tested plural suffixation and word order, the morphosyntactic structure of the language. The Mandarin task tested participants’ knowledge of aspect markers and measured words. We chose to test structures that differ from English, which are commonly lost by heritage speakers. They also included romanization and audio recordings of the tasks to account for the varying degrees of literacy.

The elicitation tasks consisted of a story-retelling exercise where the participants were virtually shown an animated short story from Youtube in the heritage language and then asked to retell the story in the heritage language. A Likert scale was then used by a native speaker to judge each participant’s fluency levels as they viewed the recording of the participant’s elicitation.

Results

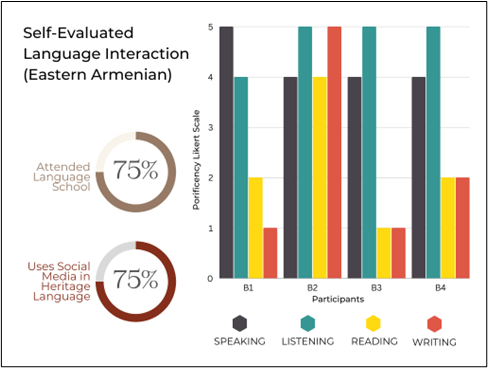

Figure above shows that more than half of the participants use social media in their heritage language and received formal education in Armenian.

The participants in the study varied in the production and comprehension levels of their respective heritage languages, and their use of social media in the heritage language.

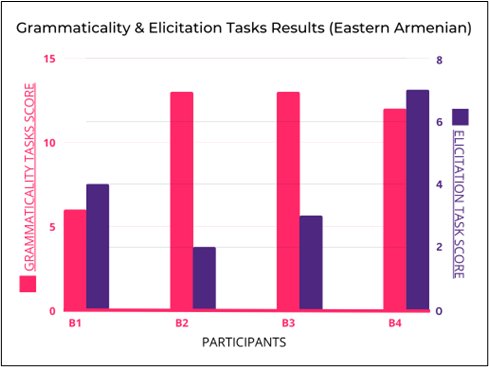

Eastern Armenian heritage speakers varied in their production and comprehension levels of the language. Based on the results of the elicitation and grammaticality tasks, it appears that receptive knowledge is not necessarily related to expressive knowledge. For instance, the native speaker ranked participants B2 and B3 as the lowest proficient speakers of the heritage language, but these same participants had two of the highest scores for correctly identifying grammaticality judgments in their heritage language.

Figure above shows that participants had varying results on the grammaticality judgment tasks and the elicitation task. Only B4 has high scores on both tasks.

Additionally, the Eastern Armenian heritage speakers who score the highest on the elicitation and grammaticality judgment tasks consumed social media in various amounts, ranging from rarely or never to as frequent as daily consumption. Participants B2 and B3 scored the highest on the grammaticality judgment tasks, but B3 said that they rarely or never consume social media in their heritage language, while participant B2 did so on a daily basis, in formats of video, audio, and text. Participant B4 scored highest on the elicitation task and the second highest on the grammaticality judgment tasks, and used social media in the form of Instagram video multiple times a month. Lastly, participant B1 scored the lowest on the elicitation task and had a somewhat low score on the grammaticality judgment task. They consume social media in their heritage language on a weekly basis in the form of audio and text.

All in all, the data from our Eastern Armenian speakers does not represent any correlation between social media usage and heritage language competence.

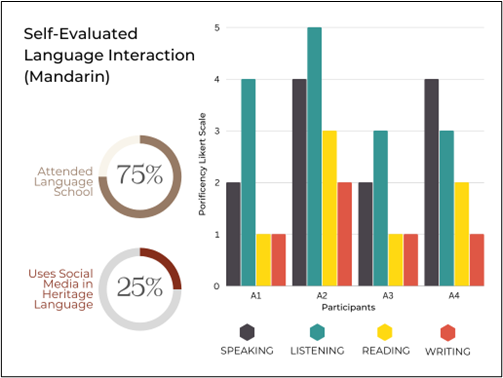

Figure above shows that more than half of the participants received formal education in Mandarin and only a quarter of the participants use social media in Mandarin.

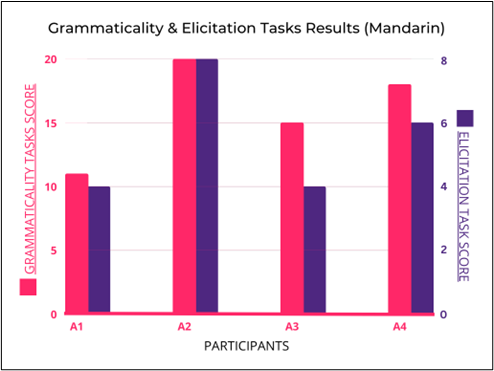

Our Mandarin heritage speaker participants also varied in their levels of fluency. Diverging from the lack of relationship we observed in Armenian, those who performed highly on one test usually performed highly on the other. Only one of our four participants for Mandarin, participant A2, expressed consumption of social media in Mandarin, and this participant also had the highest score on the grammaticality judgment tasks. This speaker could serve as one data point to support our hypothesis that heritage language social media consumption is correlated to higher levels of retention in the heritage language. However, participant A4 scored second highest on both tasks, but they do not consume social media in Mandarin. Participants A1 and A3 also do not consume social media in their heritage language and received lower scores on both tests. Although the rough possibility of a correlation exists in the Mandarin data set, there is not enough evidence to definitively support our hypothesis.

Figure above shows that participants had varying results on the grammaticality judgment tasks and the elicitation task. Only A2 has high scores on both tasks.

Discussion and Conclusion

As a result of our investigation, we were unable to find supporting evidence for our initial hypothesis that higher social media consumption in the heritage language corresponds with higher competency in the heritage language. Some factors that led to this conclusion is the lack of concrete and frequent social media usage among the participants. For instance, in the Mandarin heritage speakers cohort, participant A2 claimed they use social media and received the highest scores on both tasks as seen in Figure 4, however, participant A4 who claimed they don’t use social media got the second-highest scores in the task. Similarly, in the Armenian heritage speaker cohort, participants B2 and B3 received similar results in both tasks (Figure 2) and the two highest on the grammaticality judgment task. However, participant B3 claimed they use social media never/rarely, while participant B2 uses social media on a daily basis. The contrast can be thought of to be due to formal instruction in the heritage language.

Our new finding, formal education, correlated with higher scores on both tasks. For instance, participants B2, B3, and B4 received formal instruction in learning Eastern Armenian. The Mandarin heritage speaker who performed the highest on both tasks, A4, also received formal education in Mandarin. This correlation was of interest for other scholars who claim that the lack of formal education has negative effects on the acquisition of the heritage language; children who don’t receive formal education do not learn the formal registers, vocabulary, and complex structures in written language (Montrul, 2010). Our data reflects the aforementioned claim as the participants who did not receive formal instruction in Eastern Armenian and Mandarin performed the lowest or second lowest on the grammaticality judgment task which tests their knowledge of the language grammar. While formal education can be a factor that influences higher competency in the heritage language, this correlation has to be interpreted in terms of production or grammatical knowledge. This is because the participants who received formal education performed well on the grammaticality judgment task, but not as well on the elicitation task. These results show that analysis between formal education and heritage language competency should be further investigated.

Another factor that can influence the participant’s competence in the heritage language is the age of exposure. There is contrasting data on how the age of exposure relates to language competence. Proponents of the Critical Period Hypothesis claim that children should be exposed to a language at a certain age to be able to acquire it native-like (Mahootian, 2020). Others claim that other factors such as ‘the child’s temperament or motivation’ can affect their learning of a language (Yuldasheva, 2021). In our research, we found that 7 out of the 8 participants in our study claimed that they were exposed to their heritage language from 0 to 3 years old, with one exception, A4, who claimed they were exposed to their heritage language from 4 to 8 years old. In addition, more than half of the participants, 5 out of 8, claimed that they were exposed to both English and the heritage language at the age of 0-3, simultaneously. The participant who performed the best on both tasks in Mandarin claimed to have been exposed to English and Mandarin simultaneously from the age of 0-3. The participant who performed the best on both tasks in Eastern Armenian stated that they were exposed to English from the age of 4-8 and Armenian, from the age of 0-3. This shows that age of exposure may not play a major role in the heritage speaker’s language competency. Perhaps, the difference lies in simultaneous and sequential bilingualism. Age of exposure to the heritage language may be a sufficient factor in the heritage language competency, however, this factor has to be accompanied by other factors, perhaps, social media consumption and formal education in the heritage language.

Another finding is that there may be a correlation between longer attendance to formal instruction and higher social media usage. Social media in the heritage language provides an extension to the traditional classroom setting. Going back to Zhao & Flewitt’s case study, heritage language speakers’ language practices on WeChat extended their “Chinese-speaking social world and provided them with opportunities to engage in contextualized, transnational heritage language and literacy practices beyond their home and Saturday Chinese school environment.” (Zhao & Flewitt, 2020). We could make the claim that formal instruction and social media in the heritage language complement one another to learn, and a longer history of instruction may motivate the bilingual speaker to seek more natural and conversation-based learning environments, such as social media.

Overall, claiming that the heritage speakers’ competency in the heritage language correlates with their social media consumption would be invalid based on the findings of our research. Other variables that can account for this contrast are formal education in the heritage language or age of exposure to the language. Perhaps, formal education in the heritage language could account for these three heritage speakers’ higher performance on the grammaticality judgment and in one of the cases, the elicitation task. In a similar manner, the age of exposure to the language can be a variable that influences the results. A detailed analysis above shows that these are sufficient factors of heritage language competency and the limitations of our study prevent further research into these variables. Some of the limitations of our study include a smaller sample size. With a larger sample size, the findings of our research could be more reliable and generalizable.

However, it was interesting to see a small sample size showcase such a wide variety of language proficiency. Bilingual heritage speakers have unique backgrounds in their heritage language because of many internal and external factors, such as “the role of the school system and other institutions, the historical experiences of particular language communities, the unique circumstances involved in the adoption by some communities or individuals of proxy HLs as part of the complex multiple identities of contemporary life, and the specifiable impact of a language ecological pattern over the life cycle of individuals and families” (Lo Blanco, 2001). Our participants had different characteristics, such as high proficiency in listening but lower proficiency in writing, or vice versa, as well as the amount of formal education, ranging from a couple of years to over 10 years.

For future research, if these methods are adapted, we suggest that elicitation tasks are performed in an in-person setting rather than virtual, where the native speaker listens to the heritage speaker’s elicitation and rates them in person. Additionally, the elicitation tasks should be reviewed by different native speakers. We believe that these changes will allow the results to be more reliable and generalizable.

References

Lo Bianco, J. (2001). Language Policies: State Texts For Silencing and Giving Voice. Difference, Silence and Textual Practice: Studies in Critical Literacy, 31-71.

Mahootian, S. (2019). Bilingualism. Routledge.

Montrul, S. (2010). Current issues in heritage language acquisition. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 30, 3-23.

Moring, T., Husband, C., Lojander-Visapää, C., Vincze, L., Fomina, J., & Mänty, N. N. (2011). Media use and Ethnolinguistic Vitality in bilingual communities. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 32(2), 169–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2010.541918

Nakamura, J. (2019). Receptive bilingual children’s use of language in interaction. Studies in Language Sciences, 18, 46-66.

Yuldasheva, D. (2021). Age and The Second Language Acquisition. Research Jet Journal of Analysis and Inventions, 2(04), 124-130.

Zhao, S. (2019). Social media, video data and heritage language learning. In G. Falloon, J. Rowsell, & N. Kucirkova (Eds.), The Routledge International Handbook of Learning with Technology in Early Childhood. Routledge.

Zhao, S., & Flewitt, R. (2020). Young Chinese immigrant children’s language and literacy practices on social media: a translanguaging perspective. Language and Education, 34(3), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2019.1656738.