Nikki Lee, Kiara Mares, Jamie Seals, Ally Shirman

In everyday conversations, bilingual speakers frequently code-switch between their languages. With our modern society, we can see this becoming prevalent in media during emotional scenes with bilingual characters; specifically in movies and TV shows. In this study, we investigated three different shows and movies with bilingual actors who use their heritage language as a part of their character to see whether there is a correlation with code-switching in highly emotional situations. We chose three sources to gather this data that have at least one bilingual main character; Jane the Virgin (2014), Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), and Modern Family (2009). For each source, we analyzed around 120 minutes to have an equal amount of data. Analysis of this data found that code-switching during emotional scenes did occur, but was more prevalent in more recent media. The study helps to show that code-switching is becoming more representative for bilingual speakers in modern media.

Introduction and Background

Entertainment media heavily relies on creating a connection between the viewers and the characters and themes presented. The characters in media are often the biggest attraction because of their relatability. Thus, the representation of characters with different backgrounds, including gender, ethnicity, age, socioeconomic status, etc. is very powerful in shaping viewer and societal perceptions. Characters rely heavily on language and emotion to give away key details and shape who they are and what their role is. This is especially evident in American entertainment media with actors who play ethnic characters, with cultures other than dominant U.S. culture. Bilingualism and code-switching are some of the biggest tools used to portray identity within these characters’ roles. This makes their heritage language use very strategic and intentional for character depiction. Recognizing the power of media and how it aims to reflect real-life ideas, our project focuses on where entertainment media uses second languages, and how it intersects with emotion to reflect ideas about a language or a character.

Our project focuses specifically on bilingual actors within entertainment media who use their heritage language as part of their character. We want to investigate when this heritage language is used and if it is associated with highly emotional scenes or situations. Research on language and emotion in real-life scenarios has indicated that language use and choice can be influenced by emotions that we correlate with that language. Looking specifically at American media, our goal is to observe whether or not heritage language use occurs in more emotional situations than non-emotional scenes, and identify if there are emotions that occur more often in a heritage or dominant language. This project will be focusing on language contexts, both positive and negative, and then observing what language it occurs in. Based on our own experiences with code-mixing, media depictions, and language perceptions, we hypothesize that in highly emotional situations, characters will code-switch to their heritage language, other than English. We predict that the characters are written to represent real-life bilingual speakers to deepen their character and the media. Many viewers may find this relatable or can connect with the cultural identity of both languages being presented – which could contribute to further media representations.

Gaps in Research

Though bilingual speakers often use one language in specific settings, and the other in other settings (e.g. heritage language at home and in informal contexts, and dominant language in formal settings like work, especially if that second language is the standard language of their country), they also often use both languages at once (Ferguson, 1959). This most commonly happens when speaking to other bilingual people, but it does happen elsewhere as well. This use of both languages at once is referred to most commonly as code-switching, where interlocutors will use both languages at their disposal within the same utterances, often without consciously making the decision to do so. Though there are many ways and uses of communicating via multiple languages at once, a prominent trigger for code-switching comes from emotionally arousing situations. One study found that, through direct observation of participants in a high-stress problem-solving task, people code-switched more frequently when expressing negative emotions. Specifically, participants switched to their heritage language to express these negative feelings rather than using the dominant language (Williams, Srinivasan, Liu, Lee, Zhou, 2020). We anticipate that our study will recognize some of the same characteristics of code-switching and plan to focus on a character, then identify the number of situations in which this occurs.

Additionally, in these highly arousing emotional situations, it is more likely that speakers use their first language to react, rather than their second language. We see this in the study conducted by Ariana Mohammadi titled, “Swearing in a second language: the role of emotions and perceptions.” Additionally, a study conducted by Shahrzad Mahootian covers these emotional situations in their study and they state, …the list of evocative switches was “more meaningful” in Spanish, that they carried “more emotional power,” (“emotional statements will be said in Spanish. English is not sufficient”) that they were used to “create solidarity,” that they were “much stronger” when said in Spanish (Mahootian 2005). This study helps to show how speakers would be more motivated to code-switch in order to convey their words more effectively between themselves and their listeners. As we have shown, there has been a good amount of research done on the connections between code-switching and heritage language use with emotion but this research has not been carried over to the media. There has not been research done specifically on character use of code-switching and heritage language use and the emotion of their character or scene. We hope to fill this gap with our research in this project and we can anticipate that the media we have chosen for our study will be able to reflect these previous findings.

Methods

To understand whether code-switching occurs in half or more emotional instances in media, we used three sources that each include at least one bilingual main character and are from the 21st century. Specifically, Jane the Virgin (2014), Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022), and Modern Family (2009).

Additionally, we made sure that all three of these sources’ bilingual characters’ heritage languages were relevant to the characters themselves, but not a dominant focus for the storylines. All bilingual characters were interacting in a space where their heritage language is not the dominant language (which is English in all three sources).

We analyzed roughly 120 minutes of each source to ensure that the amount of data we collected from each would be equal, based on the length of Everything Everywhere All at Once. (We looked at three Jane the Virgin episodes (each ~40 minutes), and 6 Modern Family episodes (each ~20 minutes)).

We noted (coded) each instance of an emotional scene in each source, as well as instances of code-switching within these emotional scenes. This would allow us to calculate a ratio (number of code-switching instances in emotional scenes divided by the total number of emotional scenes), and thus a percentage, to understand how accurate our hypothesis is.

Before coding each source, we defined what “emotional” meant to ensure that each researcher was coding via the same guidelines. Highly emotional instances could come in the form of:

- Voice: raised voice, yelling, screaming, whimper

- Exaggerated body language

- Clearly emotional facial expressions that last (e.g. no microexpressions)

- Crying

Results

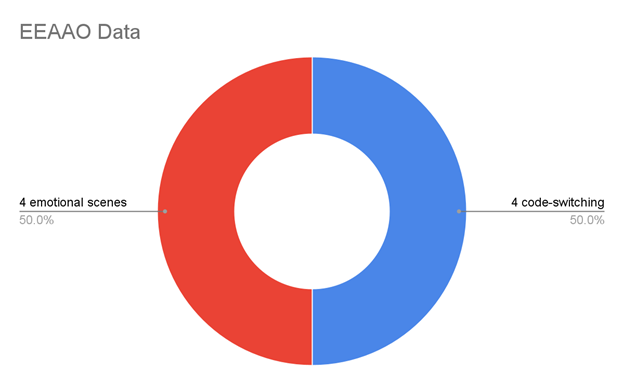

Everything Everywhere All At Once

4 code-switching instances in 8 total emotional scenes → 50% code-switching

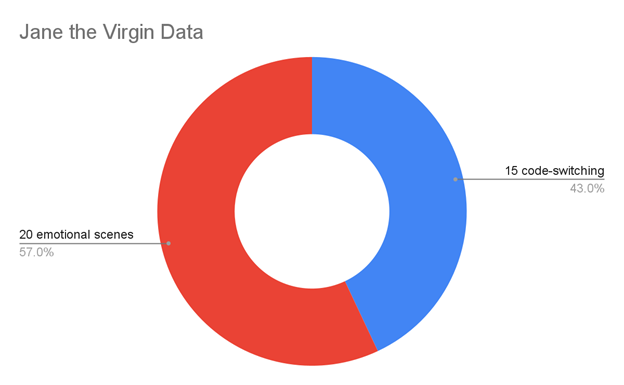

Jane the Virgin

15 code-switching instances in 35 total emotional scenes → 43% code-switching

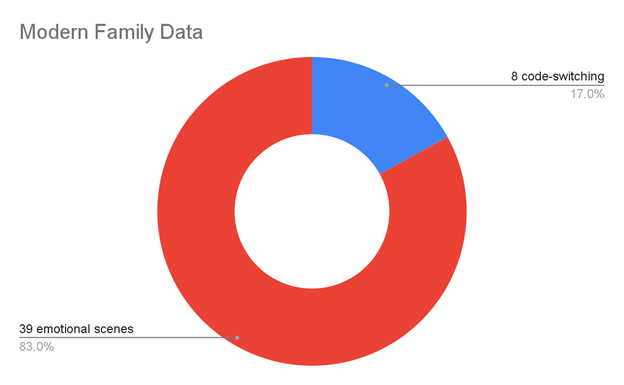

Modern Family

8 code-switching instances in 47 total emotional scenes → 17% code-switching

Combined: 27/90 → 30% of all emotional scenes across the three sources included code-switching.

Everything Everywhere All At Once was the only source to meet the hypothesis that at least half of the emotional scenes would include code-switching. However, it is important to note that there was quite a bit of diversity in how many instances of emotional scenes there were per source. Everything Everywhere All At Once only included eight, likely because it has deep themes compared to the sitcom-like shows, and the scenes are generally longer. Modern Family, on the other hand, is fast-paced (only 20 minutes per episode) and includes generally more exaggerated characters, leading to their behaviors being more exaggerated and emotional as well. This is reflected in the 47 total emotional scenes, compared to the eight from the movie.

However, even though Modern Family had the most emotional scenes, it had the lowest ratio (17%) – this is likely because there is only one bilingual character (Gloria), giving her fewer opportunities and reasons to code-switch (e.g. code-switching out of instinct when stepping on a Lego, versus code-switching to communicate an idea to someone who also speaks English and Spanish that she wouldn’t otherwise be able to explain).

Visual Media

Patterns and Analysis

Results of our study did not exactly align with our data but did highlight some interesting patterns. There were three particular patterns that were recurring in the data and had a similar basis to previous research in the realm of bilingualism in the media.

The first pattern observed from our data was the use of bilingual code-switching for reference terms. In all three of the media forms, characters code-switched when referring to another character they were close to or comfortable with. In Jane the Virgin, this was observed with the consistent referral to Jane’s grandmother as “abuela,” even when the rest of the sentence was in English. ‘Gloria’ in Modern Family also did this frequently when referring to her husband with terms of endearment such as “mi amor” (season 9, episode 3) and when referring to Haley’s children as “mis niños” (season 11, episode 6). This pattern touched on previous research that found that heritage language is used when speakers are more comfortable, which would make sense for using with family (Cho, 2015).

Modern Family Phil makes Gloria cry

Another pattern observed was use of bilingual code-switching as a form of addressing certain audiences. During scenes where characters were in the presence of other bilingual characters, or when they wanted to speak to someone directly, sometimes to the extent of using language to be private. This example was seen in Everything Everywhere All At Once when ‘Evelyn’ is standing up to ‘Gong Gong’ and switches between languages to focus on different scenarios, despite him understanding each of the languages. Evelyn chooses to code switch from Cantonese, English, and finally Mandarin to allow the listeners of that scene, her daughter and husband, to better understand her feelings. Other scenes like in Jane the Virgin used code-switching to Spanish to make sure the police didn’t understand their plan of action while he was in the room. This pattern is reflective of previous research that concluded that negative languages are more typically expressed in the heritage language, which could explain why it was used to exclude someone from a conversation (Williams, Srinivasan, Liu, Lee, Zhou, 2020).

Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022) – Evelyn Stands Up To Gong Gong | HD

Jane the Virgin used code-switching to Spanish

Finally, we observed bilingual code-switching as an indicator of urgency. Characters who were experiencing a sense of urgency and trying to communicate this hurry used code-switching to do so. This example can be seen in Everything Everywhere All At Once when Evelyn is dealing with multiple stressful situations while her family members are adding to that stress, which makes her frantic. The audience can see her emotions overflow as she code switches from Mandarin to English in order to fully express her frustration in that situation. Given that urgency could be related to other feelings, such as stress and desperation, this observation came closest with our hypothesis.

Despite the shows having different content matter, being different genres and having different amounts of bilingual characters (and thus different instances of code-switching), these were patterns that overlapped in at least two of the three media examples used. The patterns occurred in various examples throughout each of the shows and seemed to be consistent parts of the character and their role in the plot. Each of the patterns identified was relevant in various instances throughout the shows and highlighted some real-life uses for code–switching and bilingualism. Although it wasn’t what we were expecting, it definitely taught us a lot about what to expect for bilingualism in both media and everyday life.

Limitations

Within our study, there were some limitations that potentially contributed to the results being different than our predictions, but definitely impacted the process. In relation to content, our project primarily focused on three media examples. Had we used more than two shows and one film, our results may have had more range in code-switching and examples of bilingualism. Essentially, a wider range in media examples would have been more beneficial for getting a wider scope of media examples. This connects with the second limitation: variation within the media content examples. Modern Family definitely had more “feel-good,” positive moments which is different from Jane the Virgin which dealt with heavier themes and was more of a drama. While this variation was definitely better for maximizing examples of bilingual code-switching, the lack of consistent storylines and genres didn’t allow for the same amount of opportunities for code-switching during impassioned speech. Instead, the variation in content and storylines would have made code-switching more of a chance occurrence than a predictable feature.

Finally, perhaps the most impactful limitation in our research project was that most characters were the only bilingual characters in the show. This was specifically the case for Modern Family, where ‘Gloria’ was the only character who spoke Spanish and didn’t have any other main character to speak it with. In Jane the Virgin, even though ‘Jane’ and ‘Xiomara’ were Spanish-English bilinguals, they would respond in English and ‘Abuela’ was the only one who spoke Spanish the entire time. Each of these limitations could have contributed to the results and for future studies would be important to avoid.

Future Study

Considering the limitations previously mentioned and in collaboration with the patterns mentioned, a refined, future study would certainly involve a wider range of media for observation. For standardization purposes, it would be important for shows to be produced and based in the US, be from the same range of years (as in our example, the last two decades/the 21st century), and have the same amount of minutes watched, but this new study would focus on shows with more bilingual characters. Considering these elements and our previous interest in bilingualism and code-switching in the media, further research conducted could be based upon media that covers different backgrounds to be more inclusive towards the American audience. We can see a trend of this from big companies, like Disney, who have produced movies like Encanto and Turning Red. With this trend of inclusivity, there is a high possibility of representation for bilingual speakers in future media. In turn, this would allow for more possible studies to look into the instances of code-switching during emotional scenes.

Conclusion

This analysis of bilingualism in media is a good first step for better understanding how bilingual and multicultural people are represented through TV, specifically to American, English-dominant audiences. However, no broad conclusions can be drawn from this study alone; without a large sample size, we may have missed important themes and patterns on the representation of code-switching from real life, or the patterns that we did find may not appear to the same degree on a larger scale.

A larger sample size, both in terms of the amount of minutes analyzed for each source, and the amount of diverse sources chosen, should be used to create a clearer picture of how writers choose to represent bilingual characters’ language use in media.

Despite the limitations and potential to make this study broader, this introductory analysis still has shown how some patterns of code-switching (proven to be common via research studies mentioned earlier) in real life are accurately represented in media as well. As the representation of multicultural and multilingual people in the United States is being more and more encouraged in American media, the more we are actually seeing it. As in Everything Everywhere All At Once – the most recent, and most diverse, media source used in this study, it was the one source that did meet our hypothesis (50% code-switching in emotional scenes).

As screenwriters continue to portray a more accurate representation of the diversity in the United States, the more we should expect to see multi-language dialogue, filled with code-switching in these shows and movies. In future studies, a specific focus on the function of code-switching by bilingual characters, both in and out of emotional contexts, could give even more insight into how multilingual and multicultural people are represented in older media versus current media. Some examples of code-switching (and code-mixing) functions include keeping conversations private from others, raising the status of the agent who is speaking, making side comments or humorous remarks, emphasizing what is being said, or reiterating something (Gumperz, 1982). Taking this approach and categorizing the linguistic reasons for code-switching would be a great potential first step for understanding where United States media companies are at in terms of true representation of the diversity in this country.

References

Cho, G. (2015). “Perspectives vs. Reality of Heritage Language Development Voices from Second-Generation Korean-American High School Students.” https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1065385.pdf

Ferguson, C. A. (1959). “Diglossia” WORD, vol. 15, no. 2, pp 325-340., https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.1959.11659702

Gumperz. (1982). Conversational code switching. Discourse Strategies, 59–99.

https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511611834.006

Lee, J. S. (2010, April 23). The Korean Language in America: The Role of Cultural Identity in Heritage Language Learning. Taylor & Francis Online. Retrieved February 5, 2023, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07908310208666638

Mahootian, S. (2005). Linguistic change and social meaning: Codeswitching in the media. International Journal of Bilingualism, 9(3-4), 361-375.

Mohammadi, A. N. (2020). Swearing in a second language: the role of emotions and perceptions. Taylor and Francis Online. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01434632.2020.1755293

Williams A, Srinivasan M, Liu C, Lee P, Zhou Q. Why do bilinguals code-switch when emotional? Insights from immigrant parent-child interactions. Emotion. 2020 Aug;20(5):830-841. doi: 10.1037/emo0000568. Epub 2019 Mar 14. PMID: 30869940; PMCID: PMC6745004