Sylvia Le, Lien Joy Campbell, Jose Orozco, Noah SS

Do you know BTS? – If you answered no, where have you been? In the past five years Korean pop music (K-pop) has undergone a global explosion. Built into the successful business model of K-pop is the central idea of English as a Lingua Franca. While several studies throughout the years have focused on code combinations in lyrics, our study addresses specifically code-switching in a less structured environment: interviews. We elected to focus on the “biggest boy band in the world” and, arguably, the most well-known and culturally recognizable act in the international K-pop industry, BTS. The central question driving us was: does code-switching correlate to the success of BTS? In this study, we focused on interviews from three parts of BTS’s career and analyzed them for the structure, type, and cause of code-switching, while also comparing the frequency to their album sales and streams. We found that while language as a tool for international growth may be tangible, it is perhaps not as productively used as we assumed.

Background

Oftentimes, musicians and artists have found language to be a barrier between them and larger, global audiences. As artists, they are responsible for their audience connecting with their work, as well as their audience connecting with them as artists – and the way we use language in conversation has a huge impact on other people’s perception of us. So, the language in which an artist communicates can play a huge role in the reception of their work and the way they connect with fans and audiences. Recently, this has been a distinct element of modern music, where global streaming and social media connection is at an all-time high. In particular, K-Pop groups have found an increasingly English-speaking audience.

Recognizing this, we chose to investigate more deeply whether K-Pop groups have relied more on code-switching when interacting with their audience. Specifically, we wanted to analyze how K-Pop groups have used English, incorporating it into their interviews, music, and public persona, to garner a wider audience, as according to Ahn (2021), English is one of the main factors associated with the success of K-pop on the world stage.

Code-switching, for our purposes, may be defined as the practice of alternating between two or more languages or varieties of language in conversation.

While plenty of K-Pop groups have, over the years, made serious international inroads, it is arguable that none have achieved as much success as the boy band Bangtan Sonyeondan, BTS. They debuted in 2013 producing and performing hardcore hip-hop music and enjoyed their first breakthrough and commercial success in 2015, after the release of HYYH, a Youth series demonstrating their evolving musical style. Alongside the shift in music, they began using “more elaborate storylines” and “multi-layered narratives” to create the BTS Universe. HYYH was aimed at the Chinese market, but after the Chinese government closed its market to K-pop in 2016 due to the THAAD crisis, BTS was one of the first K-pop bands to actively aim at the US market, the largest and most influential in the world. Now, BTS is widely regarded as the biggest boy band in the world (Parc & Kim, 2020).

Given the established desirability of the US market from Shin and Kim (2013) and an understanding of the growing power of English as lingua franca in Asia from Kirkpatrick (2010), we chose to study instances specifically of BTS’ English/Korean code-switching.

Methodology

Several studies have focused on the use of code-switching in the actual performance and songs of K-Pop. We believed that studying English in interviews would be more casual and supplement previous lyric research. We were inspired by a study conducted by Octaviani and Yamin (2020) on the triggers of code-switching in the TV show, The Immigration, and a thesis conducted by Luthfiyani (2014) based on code-switching in the TV show, The After School Club.

Our data took the form of BTS’ interviews given to English-speaking international press/media. The selection of these was based on the popularity of the interviews as well as their chronological position in BTS’s career. Exempting their hiatus years, we split BTS’ career into three parts. We analyzed the two most viewed international interviews, via YouTube, from the beginning (2013-2015), the middle (2016-2018), and the most recent part of their career (2019-2021).

As BTS present themselves as a group and to account for variance in Korean/English proficiency, we elected to analyze them as a group rather than on an individual basis. Instances of single word assent, echoing, and “noise” were not counted as instances of switching, as they generally contributed to the sound texture of the interviews rather than content.

We then analyzed BTS’s rate of codeswitching and compared this to their album sales and song streams. We also categorized the switching as intrasentential, intersentential, and extrasentential as originally introduced by Poplack (1980). We additionally analyzed the type of code-switching in relation to Blom and Gumperz (1972) and Yohena’s (2003) categorizations: situational and metaphorical code-switching. Situational code-switching is based in situations where the speakers find that they speak one language in one situation and another in a different situation with no topic change. Metaphorical code-switching happens when there is a topic change (formal to informal, official to personal, serious to humorous, and politeness to solidarity). Finally, we analyzed the contextual motivations for code-switching using the frame of functions laid out by Holmes (2013).

We predicted that the frequency of code-switching would increase in reflection of their international career growth, and that their code-switching would grow in contextual complexity in relation to growing exposure to international environments. We further predicted that the contexts of code-switching would display more metaphorical use, too, as an indicator of their growing international group identity.

Results and Analysis

Before presenting our results, there are some confounders and limitations from our study that must be addressed. One limitation was our small sample size. This was a case study done for only one band and due to time limitations, we analyzed a small number of interviews. The conductors of this research are not native Korean speakers, so some of the code-switching analysis was aided by outlet provided subtitles, which could lead to mistakes due to cultural differences in the language and phrases that are used during Korean code-switching. Finally, band-wide analysis lacks granular specificity. It is difficult to draw causational lines in band-data, there being many extraneous variables, so although our study deduces a correlation, we cannot conclude causation.

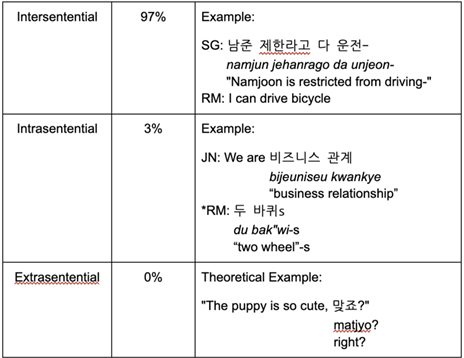

We began our analysis by looking at the structures in which code-switching occurred. We found that there was an overwhelming preference for intersentential code-switching, see Figure 1.

Interestingly, most intersentential examples were the result of turn-taking by the speaker. This points to the conclusion that most code-switching occurred independently and did not involve grammatical combinatorial structures. Typically, code-switching preferentially occurs intrasententially, as Koban (2013) confirmed with English/Turkish bilinguals. However, in this case, perhaps the semi-structured nature of interviews produces a preference for providing “complete” answers resulting in standalone sentence switches. Additionally, intersentential switching may be more accessible as they could have time to prep and foresight into normal interview questions.

In terms of the total lack of extrasentential switching observed, there are two primary possible causes. The first is that this form of switching – most often found in the form of tag questions – likely is more common in contact situations, as well as in situations where the languages occur in a more balanced distribution and particularly productive phrases remain active across both languages, which, due to the language imbalance observed in BTS, is less likely. The second possible cause is the interview format, which is not conducive to the use of tag questions.

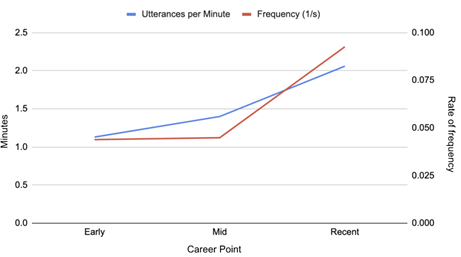

We next compared the rate of code-switching that BTS engaged in throughout their career in relation to their album sales and streams. Firstly, we found that BTS’ popularity grew exponentially over the years we studied. We compared their sales over time and the amount of their streams of Spotify over time and both showed a clear increase, as shown in Figure 2.

This was directly proportional to another criteria we considered that calculated the amount of English utterances the group produced per minute. There was a similar exponential increase with 1.13/min. in their Early era, 1.40/min. in their Mid era, and 2.06/min. in their Recent era, shown in Figure 3. This increase was directly proportional with the impact of their music and, therefore, their brand, strongly suggesting that their use of code-switching is related to their popularity and global exposure.

Additionally, we looked at the styles of code-switching that the band engaged in utilizing the framework of situational and metaphoric switching. The data samples found in Figures 4 and 5 are examples of these switches.

In our comparison of situational vs. metaphoric switching over their career, we found that there was a strong preference for situational code-switching, as seen in Figure 6.

Our data shows a general preference for situational switching overall and unexpectedly very little change in metaphoric switching. Metaphoric switching remained consistently low, even dipping to 0% in their mid-career. However, this may be due to the interviews that were analyzed for this period. This was unexpected, however, metaphoric switching is more indicative of a speaker’s internal world, or how they situate themselves in a social interaction, which lends itself to more advanced multilingual speech – this may require a higher English proficiency to be used strategically than many BTS members currently possess. This can be corroborated by the fact that many of the metaphoric switches observed were performed by RM, who is fluent in English, and the most balanced and practiced bilingual of the group.

The final aspect of code-switching that we analyzed was Holmes’ influencing factors, which can be defined as

- Participant: motivated by a change in the participants or goal receiver of utterance

- Solidarity: signaling shared group membership

- Social Context: motivated by a change in the social dimension of conversation

- Topic: motivated when a specific topic is more accessible in one language

The data samples found in Figure 7-Figure 10 provide examples of these different influencing factors.

Moreover, the complexity of code-switching exhibited in their mid and recent careers did not show the same distribution of influencing factors – with notable shifts in the prominence of Social Context and Participants. This could be due to the style of interviews, as well as growing sensitivity to interacting with English-speaking interviewers/hosts. However, the decrease in overall complexity from their early career points to a relatively consistent pattern of code-switching in terms of broad contextual influence.

Discussions and Conclusions

In recent years K-Pop has undergone a surge in popularity and groups like BTS have begun to code-switch more to relate with fans. With English being a lingua franca, we analyzed the code-switching between Korean to English from BTS. Some unexpected findings were that metaphorical switching did not increase as they began to grow. Originally, we thought that metaphorical switching would increase, but this was not the case. BTS displayed a preference for situational switching and there was little change in their metaphorical usage. We also believed that their code-switching would grow in complexity as they gained greater exposure to international environments, but this was not the case as per our research. This data is significant because it provided a greater insight into code-switching and how L2 language learners switch more in a certain style than others. It may also demonstrate that outside pressure to use an L2 language – in this case English – may not have as much effect on the actual surfacing of this language in use.

We found that most intersentential examples were member-by-member, which suggested that code-switching in this case was a standalone feature in the languages. We typically have seen new language learners start from intrasentential code-switching. This could be true for some learners, but perhaps intersentential sentences are sometimes simpler in structure and less complex. They are used in isolation, so it is easier to remember, and these types of sentences are used in everyday conversations so they are easier to pick up. So, complex mixing may be less frequent amongst BTS due to this reason, as more complicated structures require more advanced knowledge of the language. Such limited access to L2 can shape a language learner’s usage of metaphoric language as well, since it requires more proficiency in the language. Learners may struggle to use and understand metaphorics efficiently as they cannot comprehend the nuances such as with cultural references or ties. Since BTS is a Korean group, the cultural aspects of code-switching also bring in further struggles when attempting to switch to English, predominantly American English.

In conclusion, the code-switching for BTS was mainly intersentential, as the data demonstrated. There were clear preferences for intersentential code-switching over other types. We believe that this was due to the fact that the group is not very proficient in English. Based on the data that we collected, BTS code-switching has stayed relatively constant throughout the years, further illustrating the fact that they had a preference for the type of switching they use. Generally speaking, groups code-switch with friends and family when they are most comfortable. These groups may also code-switch to impress others or to send a different perception of themselves to a larger audience. Having the group code switch amongst themselves could have helped gain further attraction among fans. Meanwhile, code-switching would have also been used to convey their English skills, as it is an important language to learn in the fields of business and music.

There was an increase in overall code-switching as the group grew in international popularity. This makes sense, as they have to spread to keep up with demand. Due to this, corporations tend to gravitate to these markets where they can capitalize the most. From this standpoint, it makes sense as to why groups like BTS code switch to English rather than another language, or why their prevalence is so large among English-speaking nations and across the world. However, with the rising popularity of K-pop and Korean culture internationally, too, there has been a spike in Korean language and culture studies, so perhaps there will be a lessening of overt pressure to perform multilingualism in the future. Overall, it appears that the usage of English has aided BTS’ popularity; however, it may not be as definitively related to their success in the international music industry as we assumed.

While there were certain limitations to our study, as mentioned previously, in the larger phenomena of linguistics and bilingualism with its relation to code-switching, the data and analysis we had created could be important for future work. Future research could focus on the effects of code-switching on BTS’ audience and their reactions to it rather than how often they code-switch and why, encompassing whether or not the perception of code-switching amongst fans enhances or detracts from their appreciation of the music. On a similar note, we could also analyze the cultural implications of code-switching and how it impacts Korean culture on a global scale. This data can help future researchers better understand code-switching and its impacts on an audience relating to global sales, popularity, and positive outlook.

References

Ahn, H. (2021). English and K-pop: The case of BTS 1. English in East and South Asia, 212-225.

Blom, Jan-Petter, and John Gumperz. (1972). “Social Meaning in Linguistic Structures: Code Switching in Northern Norway.” In: John Gumperz and Del Hymes (eds.): Directions in Sociolinguistics:Sociolinguistics: The Ethnography Communication, 407-434.

Holmes, J. (2013). An Introduction to Sociolinguistics (4th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833057

Kirkpatrick, A. (2011). English as an Asian lingua franca and the multilingual model of ELT. Language Teaching, 44(2), 212-224. DOI:10.1017/S0261444810000145

Koban, D. (2013). Intra-sentential and Inter-sentential Code-switching in Turkish-English Bilinguals in New York City, U.S. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 70, 1174–1179. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.01.173

Luthfiyani, F. (2014). Code-switching and Code Mixing on Korean Television Music Show After School Club (thesis). UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta: Fakultas Adab dan Humaniora, Jakarta.

Nilep, C. (2006). “Code-switching” in Sociocultural Linguistics. Colorado Research in Linguistics, 19. https://doi.org/10.25810/hnq4-jv62

Octaviani, Andita Dyah & Yamin, Haruki Manik Ayu. (2020, July 30). The Rise of English Among K- Pop Idols: Language Varieties in The Immigration. Proceedings of the International University Symposium on Humanities and Arts (INUSHARTS 2019), 117-121. DOI: 10.2991/assehr.k.200729.023

Parc, J., & Kim, Y. (2020). Analyzing the reasons for the global popularity of BTS: A new approach from a business perspective. Journal of International Business and Economy, 21(1), 15-36.

Poplack, S. (1980). Sometimes I’ll start a sentence in Spanish y termino en Español: Toward a typology of CS. Linguistics 18, 581-618.

Shin, S.I. & Kim, L. (2013). Organizing K-Pop: Emergence and Market Making of Large Korean Entertainment Houses, 1980–2010. East Asia 30, 255–272. DOI: 10.1007/s12140-013-9200-0

Yohena, S. O. (2003). Metaphorical code-switching revisited. (Vol. 38, pp. 138–158). essay, Ferris University.