Danbi Jang, Louise Chen, Katherine Escobar, Alena Hong

Bilingual speakers code-switch for conversation consistency. Code-switching is more effective when describing cultural words with only that language and when both speakers are in an argument situation because code-switching increases conversation compatibility. Our research looked at the Kim’s Convenience Season 1 show and analyzed the Korean-Canadian bilingual family code-switching pattern. We analyzed Kim’s family’s conversation and found that intra-sentential code-switching is the most frequent type. Additionally, we realized that the function of each code-switching frequently happens for expressing identity, objectification, interjection, and clarifying repetition. The results showed that bilingual code-switching is necessary and efficient between two bilingual speakers when they intend to create connections with each other or solve problems. As a result, code-switching creates smoother conversations for bilingual speakers so they rather naturally mix two languages than only talking in one.

Introduction and Background

If you are a bilingual speaker, you must code-switch at least once. Bilingual communities frequently use code-switching. It has become a powerful communication tool for expressing and developing language skills. Code-switching is the process in which a bilingual (or multilingual) person alternates between two (or more) different languages in a bilingual (or multilingual) communication environment. There are several reasons bilinguals do code-switching. According to past research by Stępkowska (2022), bilingual people may demonstrate dissimilar verbal behavior in their two languages. Interlocutors perceive languages differently depending on their language in a given context. Additionally, attitudes toward languages permeate daily life and impact communication patterns within the couple (ibid.). Based on past research, we were curious whether bilingual speakers are more compatible than speakers who do not code-switch. According to another research, code-switching gives “a built-in sensibility that conversational regularities are both content-independent and context-sensitive” (Dumanig et al., 2015). Therefore, our research question is how bilingual speakers code-switch to communicate effectively. We mainly focused on Korean-Canadian bilingual speakers’ families and close friends, as well as investigated how Korean-English bilingual speakers code-switch to communicate effectively in complicated discussion situations and daily life.

Methods

We mainly collected data from the show Kim’s Convenience, season 1. We observed code-switching in bilingual speakers, how frequently they switched, and what purpose and function the code-switch served to communicate with other bilingual speakers in conversations. We attempted to provide transcriptions of specific examples of code-switching. We analyzed the type of code-switching primarily in categories of Inter-sentential, Intra-sentential, and Extra-sentential code-switching. We defined Inter-sentential code-switching as the language switch done at sentence boundaries, like sentences before, in the middle, or after another sentence. In our data, we have mostly seen this type of code-switching in fluent bilingual speakers. Intra-sentential code-switching is done within the sentences, with no pauses or interruptions to indicate a shift. The speakers in the show usually switched this type when they called Korean appellations, or greetings within part of the sentence. Finally, we found extra-sentential code-switching, which is switching a slang or a single word from one language to another (ESEN, 2022). In addition, we defined culturally related words or phrases such as 갈비찜(galbi-jjim) and those expressing feelings and interjections as extra-sentential code-switching.

Furthermore, we investigated the functions and purpose of code-switching and how the speakers resolved their disputes and communicated well based on the context of conversations. We classified the functions of code-switching into four which are interjections, objectification, clarifying repetition, and expressing identity. Then, we focused on examining when the bilingual speakers use code-switching to communicate more effectively in the conversation. Also, we quantified whether the data retrieved from the show conveyed more compatibility and resulted in conflicts resolved by observing any frequent types of code-switching and different functions of code-switching in speech patterns of the show. We hypothesized that code-switching plays a different role in each context, helping promote effective communication.

Results and Analysis

From the data we collected, we observed that code-switching is a highly-efficient communication tool for the Korean-English bilingual Kim’s family. At the same time, there are several talks taking place in between the monolingual speaker and the bilingual speaker. In the same way that code-switching helps bilinguals solve problems more easily and quickly in situations where there might be an argument, misunderstandings tend to last longer and occur more frequently in monolinguals because they cannot do code-switching. For instance, in episode 7 from 18:15-19:13, there is a good example of a monolingual and bilingual argument about Taekwondo and Hapkido that doesn’t go smoothly. Here we include a shortened version of the script.

Mr. Kim: wah you know 태권도(Taekwondo)?

Customer: Not really but I’m a big fan.

Mr. Kim: They have 태권도 (Taekwondo) in Africa?

Customer: oh yeah! Somalia won silver at the 2003 international open.

Mr.Kim: wow impressive! You don’t look Somalian.

Customer: No I’m not. This is just a Taekwondo fact.

Mr. Kim: 태권도(Taekwondo) is Korean.

Customer: I know.

Mr. Kim: I am a Korean

Customer: I know.

Mr. Kim: 합기도(Hapkido) is Korean too!

Customer: Hapkido?

Mr. Kim: Yea but the much better fight style! Choi he invited 합기도(Hapkido) while serve in the military in Japan.

Customer: So.. in a way it could also be considered as Japanese martial art.

Mr.Kim: No! (angry face) You joking me?

Customer: no… I just meant… Taekwondo was invented by Korean too?

Mr.Kim: Of course Korean!

Customer: I didn’t realize Korean was that strong!

In this case, Mr. Kim and the monolingual customer have a small fight because the customer does not truly know about Taekwondo or Hapkido, but he thinks he does. So, the original topic was to discuss a group of children learning Taekwondo, but due to the misunderstanding, Mr. Kim needs to expand more about Taekwondo and Hapkido knowledge. In a way, it implies that there is a higher chance for monolingual speakers to have misunderstanding or misapprehension thus reducing the consistency of the conversation. When the same situation happens on two bilingual speakers, they don’t need to stop and explain the content of their code-switching. According to Brezjanovic-Shogren (2002), code-switching “establishes a connection between the contributions of the participants thus making the conversation coherent. Considering participants are always “talking about something”, focusing on the “description of the topic” will answer directly what is the topic of the conversation.” This suggests that code-switching helps speakers stay on a certain topic and creates consistency for the conversation. Thus, there is a positive relationship between code-switching and communication.

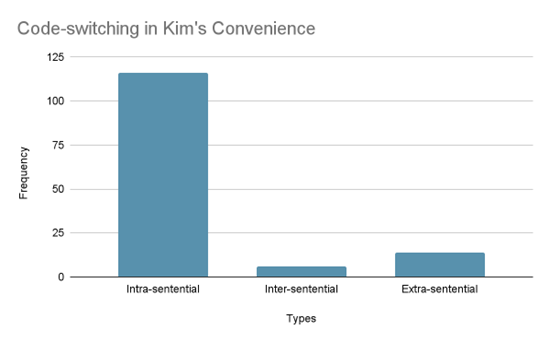

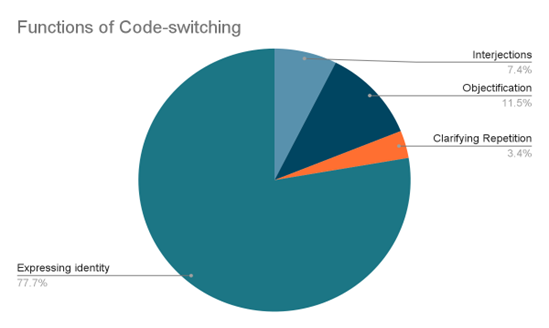

There are three types of code-switching, intra-sentential, inter-sentential, and extra-sentential. To our surprise, intra-sentential is far more numerous than the other two types (See Fig.1). This is because inserting another language phrases or words is more natural and simple than whole sentences. A significant number of these intra-sentential data come from Korean appellations, such as 아빠(Dad), 엄마(Mom), 아줌마(Auntie). The transformation of the titles into Korean reflects the function of code-switching in expressing identity and establishing connection. Prihatin (2018) proves that code-switching occurs to express identity when an individual wishes to express solidarity with a social group. According to the statistics (See Fig.2), this function is the most common one, accounting for 77.7 percent. There are also three other major roles of code-switching, namely, objectification (11.5%), interjection (7.4%), and clarifying repetition (3.4%). Code-switching uses for objectification can quickly help speakers get a more concrete image in their mind about the topic. Because this function is often present on culturally relevant code-switching, it can often be classified as the extra-sentential type. For example, Mr. Kim says Korean 합기도 (Hapkido) instead of English pronunciation Hapkido in episode 7 where the conversation takes place between him and his bilingual daughter, Janet. Because Hapkido is a Korean traditional activity, Mr. Kim wants Janet to quickly recall what 합기도(Hapkido) is and all the information related to it. This is where the advantage of code-switching comes in. Sometimes people code-switch to interrupt someone, this is the function called Interjection, doing so helps get attention or start a new topic. In other cases, code-switching is able to emphasize or reaffirm the topic when the speaker does clarifying repetition (See Appendix).

Season 1

Discussion and Conclusions

The findings from our study contributed to our understanding of interpersonal communication, more so how to make communication more effective through the use of code-switching. Our data suggests that code-switching occurs as a way to fulfill a purpose in communication such as expressing identity through the ability to relate to cultural values and strengthen relationship bonds. Additionally, through other functions such as objectification, repetition, and interjections, it improves communication by clearing any misunderstanding for phrases that do not translate well into the dominant language. In a similar field of research, Helena Merschdorf presented a TED Talk about the paradox of intercultural communication. Her studies suggest that there are invisible understandings, where biases from our primary language and culture can cause misunderstandings and misconstrue due to societal norm differences (Merschodorf, 2022). In the case of Kim’s Convenience, we found that code-switching occurred to address these societal differences. As the show was based in Canada, the respectful terms don’t translate with the same cultural significance so characters would code switch in order to express their Korean identity, avoiding an invisible understanding of potential disrespect or disregard for their Korean heritage. For example, in episode 8, the context surrounds a neighborhood pastor for Koreans, though all are welcome. The pastor is very close with the Kims as he is a frequent patron at the convenience store, but because he takes advantage of his important and influential role at the church, he believes he can get away with taking gum without needing to pay anything. The Kims are obviously worried because the continual free gum will begin to add up once rent is due, or Pastor Choi could begin to take something of greater value should he get comfortable not paying. Mrs. Kim did not want to let this continue, so she code switches and says “목사님 (Moksanim) I think we cannot…” (E8, 20:41). The purpose of this code switch was to express their Korean identity by using a formality to show respect to Pastor Choi despite telling him something that he probably would not like to hear. Because the formality does not translate in English, the code-switch in this instance eliminates a misunderstanding of disrespect as Mrs. Kim did not want to let the pastor continue misunderstanding their kindness for generosity.

Originally, our focus was to explore if code-switching would make communication more effective in couples that are in an argument. What we ended up studying was the types of code-switches and the instances in which they occur. By isolating four different purposes for the code-switch, we unveiled that by serving one of those purposes, code-switching was used to prevent miscommunication or to find a way to clarify true meaning despite a language barrier. As Merschodorf (2022) suggested, a way to prevent misunderstandings is to take into account the different linguistic knowledge from other cultures before communicating. By doing so it would prevent any marginalization or discriminatory language. This could be done through “pidgin” languages such as Konglish or Spanglish, where combining two languages that were stripped to the simplest forms, may serve as a means to accommodate both parties in a conversation in a way that keeps all cultural identities intact. Though marginalization can be perceived as a phenomenon usually concerned with targeting an individual’s identity, excluding someone through unfamiliar words and phrases without considering their needs can also be a form of marginalizing. Code-switching can then resolve this issue by allowing speakers to clarify what their true intending may be in an inclusive manner. This could be seen in episode 9 of Kim’s Convenience, where this episode follows interactions between Pastor Nina and Mrs. Kim. Mrs. Kim was dealing with embarrassment over her son’s Jung intimate relations with someone from the church, so when Pastor Nina said she heard something about Mrs. Kim, her mind was worried that there was gossip about how sexually active her son is though Pastor Nina was talking about 갈비찜, the meat dish galbi-jjim (E9, 10:03). Her attempt to code switch was to affirm and create a closer relationship with one of her church regulars, Mrs. Kim, by relating to her culture and being inclusive of the Korean language. Additionally, she asks Mrs. Kim if her pronunciation was correct, showing that she is eliminating an egocentric bias of assuming she was correct, and actively seeks feedback from Mrs. Kim as she recognizes that she is unfamiliar with Korean linguistic culture. Overall, our findings uncover that code-switching in a broader context serves to prevent misunderstandings as a result of a language barrier, through the fulfillment of communication purposes such as expressing identity, objectification, repetition for clarification, and interjections for emphasis. Without such purposes in mind, perhaps code-switching might not have an influence on the quality of communication between speakers as misunderstandings could occur without the clarification and inclusivity that code-switching can elucidate.

References

Brezjanovic-Shogren, J. (2002). ANALYSIS OF CODE-SWITCHING AND CODE-MIXING AMONG BILINGUAL CHILDREN: TWO CASE STUDIES OF SERBIAN-ENGLISH LANGUAGE INTERACTION. Wichita State University, 1-82. https://soar.wichita.edu/bitstream/handle/10057/5051/t11060_Brezjanovic%20Shogren.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

Choi, I., Kohler, R., White, K., dirs. Kim’s Convenience. 2016; Ottawa, Ont.: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). Netflix. https://www.netflix.com/browse?jbv=80199128

Choi, I., Kohler, R., White, K., writers. Kim’s Convenience. Season 1, episode 7, “Hapkido.” Directed by Dawn Wilkinson, featuring Paul Sun-Hyung Lee. Aired November 22, 2016, in Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). https://www.netflix.com/watch/80236367?trackId=14170289&tctx=2%2C0%2Cb8235341-19ea-4083-9317-21b3f05687f2-7917841%2CNES_EDA12732B35623D7FB1CFDD00F5D6A-B9F225DDE3A711-4A0417714B_p_1679516526251%2C%2C%2C%2C%2C80199128%2CVideo%3A80199128

Choi, I., Kohler, R., White, K., writers. Kim’s Convenience. Season 1, episode 8, “Service.” Directed by James Genn, featuring Paul Sun-Hyung Lee, Jean Yoon, and Hiro Kanagawa. Aired November 29, 2016, in Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). https://www.netflix.com/watch/80236368?trackId=14170289&tctx=2%2C0%2Cb8235341-19ea-4083-9317-21b3f05687f2-7917841%2CNES_EDA12732B35623D7FB1CFDD00F5D6A-B9F225DDE3A711-4A0417714B_p_1679516526251%2C%2C%2C%2C%2C80199128%2CVideo%3A80199128

Choi, I., White, K., writers. Kim’s Convenience. Season 1, episode 9, “Best Before.” Directed by James Genn, featuring Jean Yoon and Amanda Brugel. Aired December 6, 2016, in Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). https://www.netflix.com/watch/80236369?trackId=14170289

ESEN, S. (2022). Code switching: Definition, types, and examples – owlcation. Code Switching: Definition, Types, and Examples. https://owlcation.com/humanities/Code-Switching-Definition-Types-and-Examples-of-Code-Switching

Merschodorf, H. (2022, June 17). The Surprising Paradox of Intercultural Communication [Video]. TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/helena_merschdorf_the_surprising_paradox_of_intercultural_communication?utm_campaign=tedspread&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=tedcomshare

Pietikäinen, K.,S. (2014). ELF couples and automatic code-switching. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 3(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2014-000

Prihatin, Y. (2018). CODE SWITCHING USED BY ENGLISH DEPARTMENT STUDENTS OF PANCASAKTI UNIVERSITY ON FACEBOOK. View of code switching used by English department students of Pancasakti University on facebook. https://journal.peradaban.ac.id/index.php/jdpbi/article/view/358/287

Yun, S. (2009). The socializing role of codes and code -switching among Korean children in the U.S (Order No. 3356438). Available from Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (LLBA). (305085390).https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/socializing-role-codes-code-switching-among/docview/305085390/se-2