Marnie Cavanaugh, Reese Gover, Ethan Lee, Elisa Marin, Eva Reyman

Did you know that Los Angeles is the second most bilingual city in the US? Intrigued by the relevance of this topic, we were interested in taking a deeper dive into how the bilingual experience in LA shapes cultural identification and belonging, focusing on bilingual Spanish speakers. Although bilingualism can allow someone to connect to a broader range of people, we hypothesized at the beginning of our research that English-Spanish bilinguals in LA may feel cultural isolation. Feeling too American to connect to Hispanic culture, but with the knowledge of the Spanish language, too Hispanic to fit into American mainstream culture. However, our research concluded that being bilingual does not hinder one’s ability to connect with multicultural communities. Rather, bilingualism enhances it. Bilingualism helps thousands in the LA area connect with their Hispanic culture through the use of Spanish and American mainstream culture through their knowledge of English. Speech communities become expanded through their understanding of two or more languages. Cultural identification does not have to mean choosing one culture over the other. Many bilingual individuals choose to identify cross-culturally. Bilingualism in the LA area seems to be a tool to form greater connections rather than a tool that inhibits one’s ability to understand their cultural identification.

Introduction and Background

Our project examines Spanish-English bilingualism within Los Angeles, specifically focusing on how speaking Spanish and English affects the size and strength of speakers’ speech communities. Our community of practice is Spanish-English bilinguals who primarily reside in Los Angeles. Among this population, we studied the narrative aspects of language and language in use, asking bilinguals to tell their own stories through a mix of semi-structured interviews and survey responses. Using these methods, we examined how Spanish-English bilinguals in L.A. utilize their knowledge of both languages to signal belonging in various speech communities and how their bilingualism affects the communities to which they belong. Our main questions are: What role does Spanish-English bilingualism play in the size of one’s speech community within Los Angeles? Does Spanish-English bilingualism lead to increased community, or does it cause feelings of isolation? We hypothesized that, though bilingualism may theoretically create larger speech communities, Spanish-English bilinguals in L.A. may feel isolated from English- and Spanish-speaking communities.

Bilingualism is a trait that most people in the world share (Schroeder et al. 2017). But much of the bilingual experience is yet to be discovered. Our focus on the development of cultural identity amongst Spanish-English bilinguals in Los Angeles fits within the knowledge gaps in previous research surrounding this topic.

Ana Sanchez-Munoz (2018) discusses Los Angeles as a bilingual, bicultural city, emphasizing the unique role that Spanish and English speakers play in creating their sociolinguistic environment. Her research examines language practices in educational settings, finding that English is more commonly spoken than Spanish, suggesting that Spanish-English bilinguals may assume different linguistic identities in formal (i.e., educational) and casual settings. Thus, we were inspired to obtain data on the languages that Spanish-English bilinguals utilize more often in different social environments.

Likewise, Norma Mendoza-Denton and Bryan James Gordon (2011) argue that Hispanic identity is mediated through language ideologies prioritizing English speakers over Spanish speakers. Bilinguals occupy a liminal space, where they’re privileged over non-English speakers, especially in professional settings, and pressured to fit within an English-majority society through linguistic assimilation (Mendoza-Denton & Gordon 2011). Their research provides a framework for us to formulate interview questions surrounding participants’ feelings of inclusion/exclusion within English- and Spanish-speaking communities.

Moreover, Carmen Silva-Corvolan (1986) observed 27 Spanish-English bilinguals in East L.A., researching the effects of linguistic contact between multiple languages. She found that where consistent language contact occurs, linguistic simplification often follows. This is important to consider not only to understand how bilinguals may have differing levels of fluency in different languages but also because the shifts in language unique to Los Angeles bilinguals suggest the formation of unique, bilingual-focused speech communities.

Research focusing on the cognitive and developmental aspects of bilingualism helped structure our survey and interview questions. Raluca Barac and Ellen Bialystok (2012) discuss the effects of bilingualism on cognitive ability. A survey of 104 bilingual and monolingual six-year-olds found that bilingual children performed better on cognitive tasks when they received instructions in their primary language (Barac & Bialystok 2012). The findings from this study suggest that Spanish-English bilinguals may feel more comfortable utilizing the language they learned first and thus participate more in the speech communities associated with their primary language.

This literature review provided us with a baseline of knowledge. It structured our methods, allowing us to explore the topic of cultural identification among Spanish-English bilinguals in Los Angeles in an informed, systematic manner. Our findings suggest that contrary to our hypothesis, speaking Spanish is integral to participants’ feelings of inclusion in both Spanish and English speech communities. The majority of participants reported feelings of belonging to both language communities. Additionally, many participants noted that bilingualism was a beneficial attribute in their personal and professional lives.

Methods

We used three different methods of data collection to provide our project with a well-rounded, comprehensive understanding of our topic. First, we utilized a review of relevant literature (noted above) to provide context and relevant information for our research. As well, the knowledge gaps we identified justified our research questions. Second, we used a 14-question survey incorporating True/False, Likert scale, and optional open-ended questions. The criteria for survey respondents were that they are Spanish-English bilinguals primarily residing in Los Angeles; responses were anonymous, though demographic data (age, gender, primary language) was collected. Finally, we utilized a 15-question, semi-structured interview to gain in-depth, qualitative data. Each group member conducted one interview, resulting in five interviews. Similarly to survey participants, interviewees were required to be Spanish-English bilinguals primarily residing in Los Angeles. Interviews lasted 20-30 minutes each. The observable elements of communication we studied included participants’ fluency in both languages, the speech communities they most identified with and participated in, and feelings of isolation or inclusion regarding speech communities.

Results and Analysis

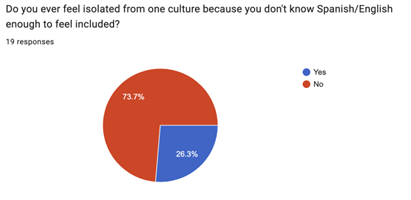

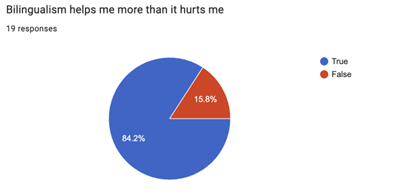

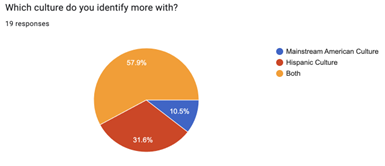

We first surveyed Spanish-English bilingualism and received nineteen responses. The survey had twelve demographic, multiple choice, true/false, and Likert-scale type questions, as well as two optional open-ended questions, where respondents could expand on their previous answers. We received seven responses for these open-ended questions, which expanded on the question, “Do you ever feel isolated from one culture because you don’t know Spanish/English enough to feel included?” We also received eight responses expanding on the true/false statement, “Bilingualism helps me more than it hurts me.” The survey questions and responses are shown in Figures 1, 2, and 3 below.

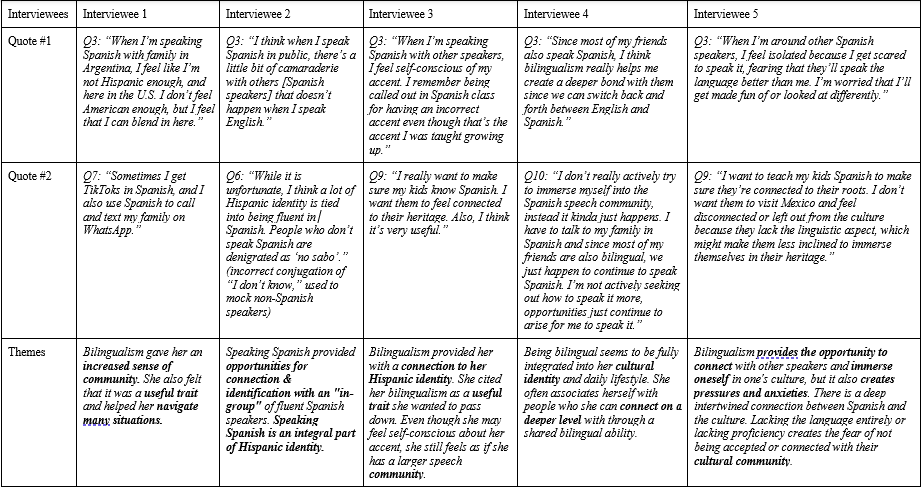

After the survey, we each conducted one interview. Table 1 provides select quotes from each interview, along with the main themes that these quotes suggest. Out of five interviewees, two specifically mentioned feeling insecure speaking Spanish and fearing they would be made fun of for their speaking ability, one interviewee stated “[in Argentina] I don’t feel like I’m Hispanic enough”. The other two interviewees didn’t mention personal experiences of feeling isolated. Despite citing feelings of isolation, interviewees also spoke about how bilingualism is beneficial. Interviewees stated that their speech community is larger and their connection to their heritage increased due to their ability. Bilingualism was seen as a positive trait that they desired to pass on.

Discussion and Conclusions

Throughout the study, we found our original hypothesis that Spanish-English bilinguals would feel isolated to be generally incorrect. Our interviewees claim that being bilingual has aided them in the way of social and professional opportunities, with one stating “I’ve had more educational opportunities since I do research in Spanish [at university]”. While two of our interviewees explicitly expressed insecurity about speaking Spanish, it was a general feeling among our interviewees that bilingualism made them feel included. Our interviewees see their bilingualism as a crucial part of their identity and a method for connecting with their heritage. Interviewees cited connection to culture as a main reason for wanting to pass on bilingualism. The data collected is useful for understanding the importance of language to Hispanic identity in Spanish-English bilinguals.

References

Ahearn, L. M. (2021). Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Wiley Blackwell.

Barac, R., & Bialystok, E. (2012). Bilingual Effects on Cognitive and Linguistic Development: Role of Language, Cultural Background, and Education. Child Development, 83(2), 413–422. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41416093

Mendoza-Denton, N., & Gordon, B. J. (2011). Language and Social Meaning in Bilingual Mexico and the United States. In The Handbook of Hispanic Sociolinguistics (pp. 553–578). Wiley-Blackwell. https://www.norma-mendoza-denton.com/_files/ugd/e4ef1f_932d492a6a7e4b73ba091db41ee046f3.pdf

Sanchez-Munoz, A. (2019). Bilingualism in California: The Case of Los Angeles. In Biculturalism and Spanish in Contact: Sociolinguistic Case Studies (pp. 51–68). Taylor & Francis/Routledge.

Schroeder, S. R., Lam, T. Q., & Marian, V. (2017). Linguistic Predictors of Cultural Identification in Bilinguals. Applied linguistics, 38(4), 463–488. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amv049

Silva-Corvalan, C. (1986). Bilingualism and Language Change: The Extension of Estar in Los Angeles Spanish. Language, 62(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.2307/415479