Griffin Gamble, Erin Kwak, Joanna Kwasek, and Hannah Shin

A heritage language is defined as a minority language spoken at home that is not part of a dominant language in society. This study looked specifically into Korean heritage speakers living in the United States and investigated whether language proficiency in Korean will align with the degree of Korean cultural identity. In order to study this relationship, we utilized two separate data collection methods: an elicitation task to assess language proficiency and a self-reported questionnaire to record cultural identity. As expected, we found that the more grammatical errors the participants made, the less they identified with their Korean culture. This finding suggests a positive relationship between Korean language proficiency and Korean self-identity, which contradicts previous findings that higher proficiency in a heritage language predicts a more balanced bicultural identity that is not dominated by one culture.

Introduction and Background

With the U.S. being known as a melting pot of cultures, numerous languages are constantly being spoken and intermingled in public and private. Following this observation, we were interested in understanding how heritage speakers–more specifically, Korean heritage speakers–juggle multiple cultural identities.

Previous findings suggest that one’s cultural identity and language proficiency are correlated. Lee (2002) studied the relationship between heritage language proficiency and cultural identity of Korean heritage speakers. They were able to observe that Korean heritage speakers who were proficient in Korean largely reported having a bicultural identity, or one that is equally American and Korean (Lee, 2002). Furthermore, Adaobi (2014) studied the link between a minority language, Etulo, and the majority language, Tiv, to understand if bilingualism affects self-identity. Similarly to Lee (2002), Adaobi found that Eluto speakers identified with both cultures, but did experience a sense of identity conflict, or dual identity, from time to time (Adaobi, 2014). Such findings indicate that proficiency in both the dominant and minority languages facilitate a unique bicultural identity.

One of the biggest limitations that we observed in the studies above was the use of self-assessments as a measure of language proficiency. Self-reports can be unreliable in producing standardized data, as it does not involve an objective assessment of language proficiency; it is susceptible to biases about how well one believes they can speak a language. Therefore, in our study, we have decided to implement a widely used method in the study of bilingualism: the elicitation task (Bialystok and Frohlich, 1980; Dechert, 1983). As grammatical competence is often a strong predictor of overall oral proficiency (Magnan, 1988), it is plausible to assume that grammatical errors will decrease as the proficiency level increases. With such assumptions, the current study conducted a grammaticality judgment of participant speech to determine language proficiency (Cornips & Poletto, 2005), in hopes of enhancing both the validity and reliability of the research addressing heritage language proficiency and cultural identity.

We hypothesized that there will be a positive relationship between Korean language proficiency and Korean cultural identity. In other words, Korean heritage speakers who 1) exhibit higher grammatical accuracy in Korean and 2) are able to utilize more cultural references will identify with the Korean identity to a larger degree.

Methods

We studied twelve Korean heritage speakers currently living in Southern California, between the ages of 15 and 23. Eight of the participants identified as female, three as male, and one as other. They had differing levels of exposure to formal Korean language education but all of them used Korean at home with their family (aligning with our definition of a heritage speaker).

The study utilized two separate data collection methods. The first was an elicitation task, which involved a slideshow that depicted the Korean fairytale titled The Heavenly Maiden. We began by telling the story to the participants in English, accompanied by the corresponding image for each scene (See Figure 1).

The participants were then asked to retell the story in Korean as we flipped through the images in the slideshow. Their speech was recorded and transcribed for further analysis. The second data collection method was a questionnaire that was distributed to participants after the elicitation task. By doing so, the questions regarding ethnicity, culture, and comfortability in speaking Korean did not influence their performance in the storytelling task. The survey also included questions about the participants’ general background information, such as their age, the circumstances in which they learned Korean, in what situations and how frequently they use Korean today, etc.

The recording was reviewed for two main variables: instances of any grammatical errors (such as subject, verb, and object word order errors) and the usage of culturally-relevant vocabulary within the story. Regarding the culturally-relevant vocabulary, there are a few terms, such as 선녀 (“heavenly maiden”) and 두레박 (“bucket”), that are important aspects of the fairytale. We expected to find that participants who are more in touch with Korean culture would be able to better identify and use those cultural references.

Results and Analysis

Out of the twelve participants, only ten participants fully participated in our study as two people opted out of the elicitation task as they felt that the task would be too difficult with their language abilities. However, we still decided to give them the option of completing the questionnaire so that we could note any potential patterns.

When analyzing the data, we noticed two main patterns amongst the participants: irregular formality and sentence structure. These were interesting to us because the Korean language is highly sensitive to different degrees of formality–that is, a speaker should not be suddenly switching between multiple formality levels unless the recipient has changed. An instance of irregular formality can be seen in this excerpt of participant 1’s transcript: “사슴이 남자에게 도움을 요청했습니다. 사냥꾼이 사슴을 사냥하고 있었다.” The first sentence ends with –습니다, which is formal and respectful. However, the next sentence ends with –다, which is less formal and more direct. Additionally, Korean sentences typically follow a subject-object-verb order, but the participants seemed to use different word order structures purposefully. Korean-American speakers were repeatedly and deliberately utilizing an alternative word order structure as a stylistic choice, not as a momentary mistake. An example of irregular sentence structure can be observed in this excerpt of participant 4’s transcript: “사슴이 살려달라고 그래서 나무속에 숨겨놨는데 사냥꾼이 와서 찾았어요 사슴을.” This sentence notably ends with an object (“사슴을”), which is not common in Korean speech, and more resembles English’s subject-verb-object order.

Surprisingly, participants were generally lacking in the use of cultural references with two people using none, seven people using one, and one person using two. Patterns regarding the usage of cultural referents were thus not evident, which made it difficult to answer the relevant aspect of our hypothesis.

Regarding the self-reported cultural identity of our participants, a majority of our participants considered themselves Korean-American, but more Korean or equally Korean and American. None of our participants considered themselves fully American with no Korean identity. Interestingly, the participant with the least amount of errors and highest self-perception of being Korean (i.e., they viewed themself as fully Korean, rated themself 5 in Korean proficiency, and 5 for how comfortable they are in speaking Korean), only utilized one cultural referent throughout the whole speech. She instead opted for a more casual and simple nuance, using Korean versions of an English word, such as “샤워” ([ɕʰawʌ] ‘shower’) and 버켓 ([bʌket̚] ‘bucket’). We also noticed that the two people who opted out of the task but filled out the questionnaire were the only ones who marked “very uncomfortable” for the question asking how comfortable they are in speaking Korean and “strongly agree” for the statement “I celebrate most American holidays.”

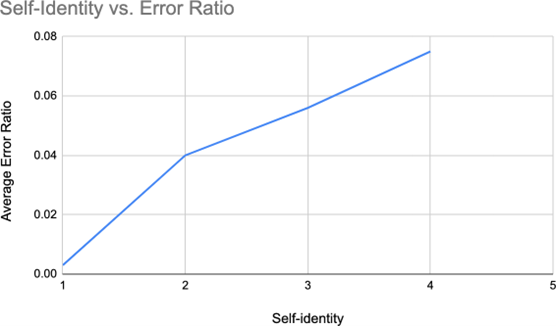

In comparing the self-identity question to their overall error ratio in speech, we found that the average error ratio increased as the participants identified as more American (See Figure 2). Although we were not able to run a formal statistical analysis due to our limited sample size, we expect this trend to transfer onto a bigger sample size as well due to its concreteness.

Another interesting observation we made was that those who marked that they took Korean in school for foreign language credit (which were participants 9, 10, A, and B) had either: the highest ratios of errors or completely opted out of the elicitation task due to low proficiency.

Discussion and Conclusion

The results suggest that language proficiency and cultural identity seem to have a positive correlation, as the participant who rated herself as fully Korean had the least errors in speech, and the average error ratio of participants increased along with American identity. In addition, we also observed a common linguistic pattern among our Korean-American participants. Those who rated themselves a score of 2 or 3, and therefore did not fully identify as Korean, were using a word order structure similar to English subject-verb-object (SVO). This word order is not technically ungrammatical in Korean, but it’s usually only used if the second clause is an afterthought therefore it can come off as awkward especially if used repetitively. However, the Korean-American participants appeared to be using it as a stylistic choice, and not by mistake. This finding opens up a new area of research for bilingualism: emerging linguistic patterns in heritage speakers that were not previously observed in native speakers. By studying how this linguistic trend is preserved or even replaced within generations, we would also be able to study how multiple languages reform as they come in contact with a different language. In the case of our participants, it was mainly the fusing of English and Korean that prompted the rise of English’s SVO-like word order structure in Korean.

One of the biggest limitations was our small sample size. A larger sample size would help identify stronger, statistically significant correlations between our variables, and in turn, promote the external validity of our findings. Furthermore, we could better target the elements within our hypothesis by improving the elicitation task. As we were unable to observe a consistent use of cultural references among the participants, we could better assess the role of cultural proficiency or cultural awareness by utilizing or creating a story that prompts the use of more cultural references. The analysis method of our study would also have been more standardized if the grammaticality judgment was not done by the researchers themselves. Although we were limited in our time and resources, recruiting a panel of native Korean speakers to rate the grammaticality of each participant’s speech would lead to a more concrete assessment of language proficiency.

So why do these findings matter in our day-to-day lives? First of all, the observations we made throughout our study support the idea of a bidirectional relationship between language and identity. Even though our main research question dealt with the positive connection between language proficiency and the corresponding cultural identity, this relationship encompasses so many other factors such as our attitude towards our culture, the amount of language use per day, the quality of language use, the context of language use, and much more. Each of the aforementioned variables could equally serve as a byproduct of or the driving elements behind one’s language proficiency. For instance, one could be using their heritage language only with their parents because they lack proficiency, or lack proficiency because they only use it with their parents and no one else. If you factor in the role of cultural identity, it further raises the question of “which came first?” as it could be the depth of cultural identity that motivates language use or vice versa. Knowing this, it brings us to the second reason why the findings of this study are important: we could potentially promote language proficiency and cultural identity by elevating one another! To provide an example, enhancing one’s cultural identity could serve as a big motivator behind learning a heritage language. The positive attitude allocated to a specific culture could definitely act as an incentive for learning a language while enhancing the learning process itself. Similarly, one might wish to identify with their heritage culture on a deeper level. The findings in this study suggest that increasing one’s proficiency in their heritage language could in turn intensify one’s respective cultural identity.

References

Adaobi, N. O. (2014). Bilingualism and identity in etulo. OGIRISI: A New Journal of African Studies, 10(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.4314/og.v10i1.2

Bialystok, E., & Fröhlich, M. (1980). Oral Communication Strategies for Lexical Difficulties.

Interlanguage Studies Bulletin, 5(1), 3–30. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43135243 Cornips, L., & Poletto, C. (2005). On standardizing syntactic elicitation techniques (part 1).

Lingua, 115(7), 939–957. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2003.11.004

Dechert, H. W. (1983). How a story is done in a second language. In C. Faerch, & G. Kasper, (Eds.), Strategies in Interlanguage Communication, 175-196. New York: Longman.

Jee, M. J. (2016). Exploring Korean heritage language learners’ anxiety: ‘We are not afraid of Korean!’ Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 37(1), 56–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1029933

Lee, J. S. (2002). The Korean language in America: The role of cultural identity in heritage language learning. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 15(2), 117–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310208666638

Magnan, S.S. (1988). Grammar and the ACTFL Oral Proficiency Interview: Discussion and Data. The Modern Language Journal, 72, 266-276.

Montrul, S. (2013). How “Native” Are Heritage Speakers?, Heritage Language Journal, 10(2), 153-177. doi: https://doi.org/10.46538/hlj.10.2.2

Rothman, J. (2009). Understanding the nature and outcomes of early bilingualism: Romance languages as heritage languages. International Journal of Bilingualism, 13(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367006909339814