Chelsea Gleason, Priscilla De Luna, Kat Dang, Briana Tena

Do males and females speak differently in a professional setting? If so, does this cause any implications? In this study, we look at the different language patterns in the popular TV show, The Office, a comedy show following the lives of workers at a desk job.

The aim of our research was to see if differences in speech establish a power hierarchy between genders in the workplace. This research was motivated by the growing number of women in higher skilled professions compared to previous decades. Thus, we developed a coding system to study the frequency of rise in pitch and use of interruptions among the characters in this TV show. We then analyzed the data and found that the speech patterns did contribute to a power hierarchy, however it was represented through men establishing dominance over other men, rather than men establishing dominance over women.

In recent decades, more women are securing higher skilled positions in the workforce compared to previous time periods in which professional work was mostly male dominated (Ziman, 2013, p. 1). There is little to no research studying the new relationships between genders in this setting, thus we conducted a study focusing on one of the fundamental aspects of interaction: language.

We completed a linguistic analysis of the American version of The Office, meaning we studied the differences in language use between individuals. The Office served as an excellent source for our study as the show has over 57 million viewers (Stern, 2018, col. 4), so the show should represent what Americans view as common speech.

To complete this study, we took a sociolinguistic approach, which relates differences in language to social factors, most notably in our case: gender. We collected our data by analyzing phonetics, which is the study of speech sounds, and via conversational analysis, which is a broad linguistic field that studies natural conversations in everyday situations. To make our data more quantifiable, we defined phonetics as the use of upspeak, which is the rising pitch at the end of a statement, or more commonly known as the “Valley Girl Accent”, and defined conversational analysis as any interruptions made between characters.

We chose upspeak and interruption because social scientists have previously found that these factors aid in creating differences in power among genders and ultimately form a gender hierarchy (Linneman, 2013, p. 83), (Schegloff, 2001, p. 289). However, there is no research indicating if this is true in a professional setting where individuals are expected to act and speak in a more polite manner.

This led us to hypothesize that the use of upspeak and interruptions in the workplace places males in a superior power position compared to females.

First, we had to research if there was any data that indicated gender inequality in the workplace, and what steps, if any, are being made to address the issue.

As of 2019, women get paid 80 cents on the dollar, compared to men, and only 79 women are promoted to a higher position compared to every 100 men (Schooley, 2019). Women in the workplace experience microaggressions verbally and behaviorally during the communications at work. These actions are both intentional and unintentional, ranging from, but are not limited to “hostile, derogatory, or negative prejudicial slights and insults.” (Schooley, 2019).

This idea is illustrated in Nidhi Dua’s Tedx Talk, “Gender Equality at Workplace.” Dua discusses the problem of obtaining gender equality, where the problem stems from, and possible solutions. Gender equality is a series of complex issues with no single, direct cause. It is acknowledged that no single person or group can solve the problem, but they can each do their part.

In order to start positive changes in the workplace, Dua believes that “engaging with men and women workers, spreading awareness, and addressing issues that act as impediments to gender equality” were important factors. The training at the factorial level consisted of : peer to peer learning, audio-visual presentations, focus-group discussions, role plays that highlight gender stereotypes, and developing grievance handling mechanisms. Dua highlighted the development of grievance handling mechanisms because women (especially) are put through tremendous amounts of stress and pressure both in and out of the workplace. Women also tend to feel uncomfortable with speaking up and reporting their incidents and concerns.

We applied this idea and studied the grievance handling mechanisms through upspeak. “Upspeak” (or “uptalk”) refers to one’s pitch rising towards the end of a statement. This speech pattern is often compared between men and women. Upspeak’s existence can be dated back to as early as the 17th century (Gorman, 1993) and its usage is common among women. This linguistic phenomenon has the connotation of being a “Valley Girl” accent, although it has become more common in both men and women since its “discovery” (Rutter, 2013).

Despite being practiced by both men and women, what upspeak determines for each gender in society varies greatly. In a study that was conducted on the show Jeopardy! By Virginia Rutter, PhD., she found that men use upspeak when they are uncertain or unconfident with their responses to a statement or question. It was also discovered that men would use upspeak more with women when they are correcting a woman compared to a fellow man. Her study indicated that men used upspeak 22% of the time when correcting another man, but was used 53% of the time with women. It is speculated that men do this as a form of chivalry towards women.

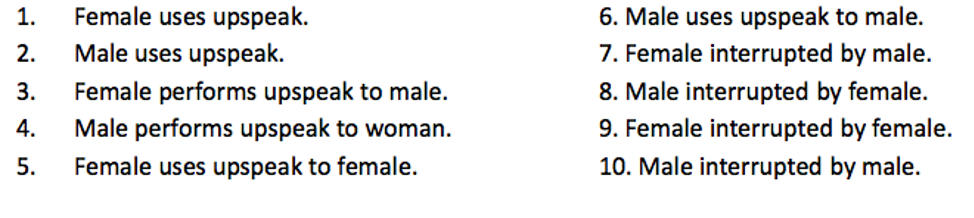

We wanted to see if these findings correlated with our study. So, we began analysis on the TV show, The Office. The Office, contains 9 seasons with a total of 201 episodes. Since there was not much time to gather all of the data, only 20 episodes were chosen to be analyzed. This way, each group member was responsible for 5 episodes. A random number generator, set to 1-201, was used to select which episodes were used. The episodes were randomly selected to make sure that the data collected was a good representation of the entire show. To analyze each episode, a system of coding was created that focused on how each gender used uptalk and interruptions (Reed, pgs. 10-11). The code used is shown below:

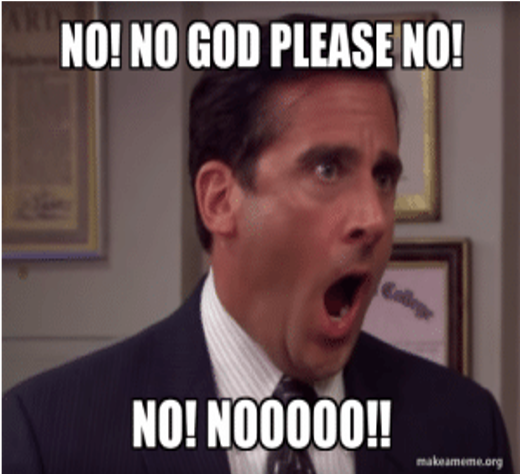

When a character used upspeak or interrupted someone, the exact words they used in the conversation were recorded. To show when upspeak was used the words were either highlighted yellow or made bold and a dash line was used to signify an interruption. For example, the scene from the image below is from the episode “Frame Toby” in season 5, episode 9 of The Office. In this scene, Michael found out that Toby came back to work at Dunder Mifflin. When Michael saw Toby he immediately interrupted Toby by yelling, “No”. This interruption was classified using the number 10 from the code, since Michael interrupted a male colleague, and recorded as shown below. There is also an example below about how upspeak would be recorded. In the second example, 2 and 6 coded the scene because Michael used upspeak when talking to Dwight.

The Office- Season 5, Episode 9 “Frame Toby” (19:52-19:48), 10 Toby: “Hi Michael-” Michael: “Noooo god! Nooo god! Please no. Nooo.” (13:04-12:57), 2 & 6 Michael: “You’re the bait for Toby?” Dwight: “Mmmhm.” Michael: “Uhh for one thing he’s not gay and if somebody were to be bait, it would be Jim or Ryan or me.”

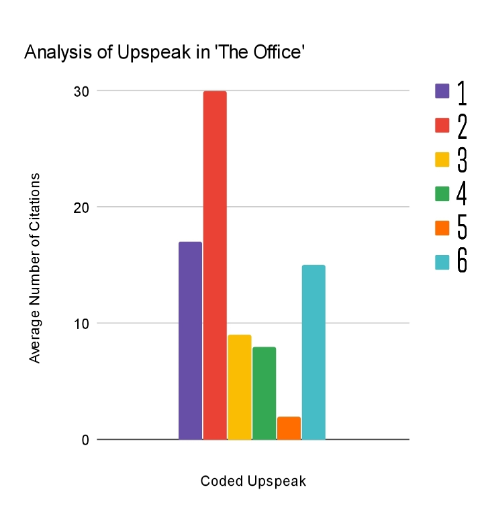

From the data, we were able to construct two different graphs to display the visual variations found when deciphering the different phonetic codes used within The Office. When analyzing coded upspeak, we found that the ratio of upspeak used in a professional setting greatly differs between men and women.

Data shows that men tend to use upspeak at least twice the given amount a woman does within the workplace. Upspeak towards the opposite sex differed as well. Women were more likely to use upspeak towards men in ratio to the amount of times men used upspeak towards women. This is an effect of lack of confidence within the workplace, thus women felt the need to critique men less often to avoid coming across as too strong. Men however, were likely to use upspeak towards women as a form of peer correction or chivalry, not as a form of dominance, hence they used upspeak towards the opposite sex less often.

Data also implies that males are more likely to use upspeak towards men as opposed to the usage of it towards women. The stark difference has led us to believe that in a work setting, men often feel the need to assert their dominance and establish a visible hierarchy amongst their male coworkers than towards women.

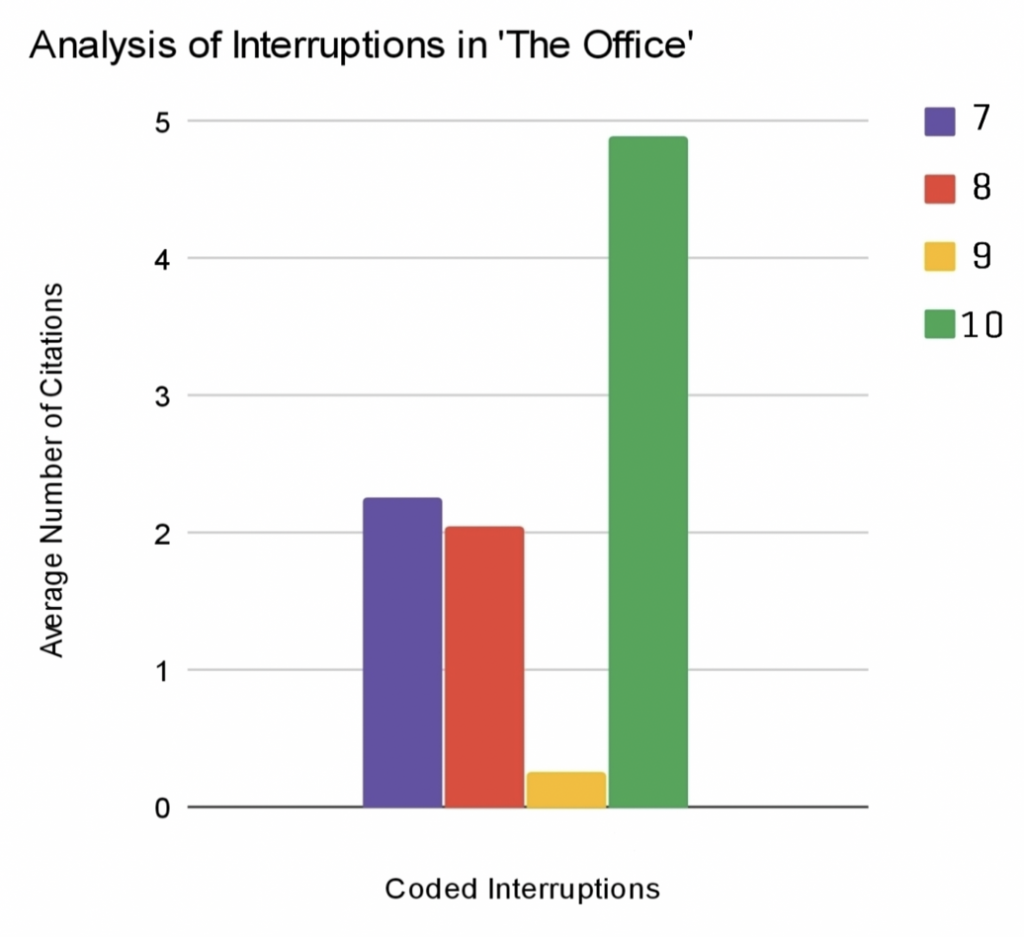

In coded interruptions, there was a small difference between data when analyzing codes 7 and 8. Females were more likely to be interrupted by males than males were to be interrupted by females. However, in codes 9 and 10, our data displayed a stark contrast of a <1: 5. Essentially, this established the notion that males are more likely to interrupt a male coworker in the workplace than females were to interrupt a female coworker.

In the original hypothesis, we expected men to use more upspeak and interruptions towards women than towards men. We hypothesized that this would occur in the form of chivalry or as a form of peer correction. Data results, however, differed greatly from our initial theory.

After analyzing the codes through a random draw of various scenes, we can infer that men used more upspeak than women within the workplace altogether. Males, however, were less likely to use upspeak towards the opposite sex than women. This correlates to the notion that women are more likely to use upspeak when speaking to men because they felt the need to be apologetic of their success.

Further analysis concluded that males were more likely to interrupt another male counterpart than a female counterpart. With this data we were able to see a clear sense of hierarchy and several dominant attributes within men in the workplace. As a result, men often establish more dominance over male counterparts through peer correction and interruptions than towards female coworkers.

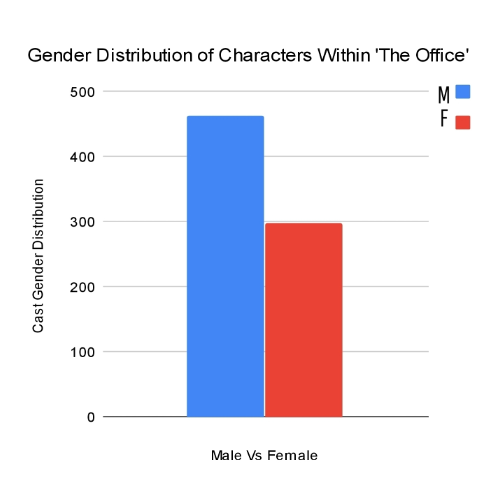

These findings coincide with the gender distribution of characters within The Office. A larger male population within this workplace can be a correlative factor that encourages males to assert dominance over a competitive atmosphere with other men. Women, however, were less likely to interrupt the same sex or use more upspeak than men since The Office is not female dominated, therefore they were not encouraged to assert their dominance like males in this setting.

References

Gorman, J. (1993, August 15). ON LANGUAGE; Like, Uptalk? The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1993/08/15/magazine/on-language-like-uptalk.html

Rutter , V. (2013, December 28). Men and Women Use Uptalk Differently: A Study of Jeopardy! – Sociological Images. Retrieved from https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2013/12/28/men-and-women-use-uptalk-differently-a-study-of-jeopardy/.

Schegloff, E. A. (2001). Accounts of conduct in interaction: Interruption, overlap, and turn-taking. In J. H. Turner (Ed.), Handbook of Sociological Theory (pp. 287–321). https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-36274-6_15

Schooley, S. (2019, May 20). The Workplace Gender Gap and How We Can Close It. Retrieved from https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/4178-gender-gap-workplace.html.

Stern, M. (2018, December 15). Is ‘The Office’ the most popular show on netflix? The Daily Beast. Retrieved from https://www.thedailybeast.com/is-the-office-the-most-popular-show-on-netflix

YouTube. (2019, February 26). Gender Equality at Workplace | Nidhi Dua | TEDxGurugramWomen. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qEtTGkICKtY&app=desktop.

Ziman, Rebecca L., “Women in the Workforce: An In-Depth Analysis of Gender Roles and Compensation Inequity in the Modern Workplace” (2013). Honors Theses and Capstones. 157.