Anthony Waller, Avery Robinson, Nicole Rasmussen, Jun Jie Li

Creativity and complexity are not often two factors that are considered when we insult; we typically go to our personal shelf of offensive phrases and let our selections do their damage. When we look at high school oriented films, however, we see that insults are a means of identity negotiation and employ creative and complex techniques that serve to compound the effect and project a strategic process of identity projection and negotiation. In this article, we will be examining how films act as a social mirror by reflecting a description of contemporary teenage culture. Specifically, we will be considering two factors that we believe to have had a significant impact on the motivation of portrayals: gender and time. Looking at several classic selections that spans the decades of the 80’s through the 00’s, we utilized a nexus and inductive approach in isolating specific linguistic elements of insults that appear most salient to our research. We conducted a series of comparative analyses of creativity and complexity parameters and extrapolated a loose correlation between gendered insults and the passage of time. From there, we will be discussing some implications of this correlation and how insulting is a process of identity prioritization and constructivism through self-isolation.

Introduction: How We Offend

For our research, we will be investigating the depiction of insults in teenagers as portrayed in films of high school settings from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s. Specifically, we want to take a look at how the complexity and creativity, as defined below, of insult formation are expressed across gender boundaries, and how the mechanism of that formation has evolved over the decades. Based on our preliminary observations, we are expecting to see depictions of greater structural complexity and communicative creativity in females characters over males. We also believe that there will be an inverse proportional relationship between the integration of elaboration in insult formation and the time period.

Background

Film can often provide valuable insights into how an era sees itself (Kalinak, 2010). Its choices shed light on realities and stereotypes, and insults and derogatory language natural entry points for analysis. Insults and derogatory language have two important, interdependent functions: the attack and distancing of the other and the defense and reassertion of the self. Teenagers are at a critical stage of self-discovery, and these functions offer insight into their views of self (Goffman, 1971). Choices in insult delivery will show the teenager’s prioritization in their identity expression, therefore by analyzing teenagers’ conspicuous insult expression, we can learn a great deal of what adults think of their successors.

The basis of our first hypothesis rests on Lakoff’s features of women’s speech. According to Lakoff, women are expected to use super-polite forms e.g. indirect language or euphemisms, and avoid swear words (Mooney & Evans, 2015). Therefore, if women want to insult someone, they would need to be more creative in order to get their point across while still adhering to the conventions of what is acceptable for women to say.

Our reasoning for predicting a general decline in complexity and creativity as we get closer to the current time is due to the improvement in technology and the emergence of “text speak,” “meme culture,” and the general notion that teenage speech has become more coded and somewhat less markedly intelligent (Brinkley, 2013, Dijk, 2016). Teenagers have found ways to say more with a lot less and to make a greater use of the referential creativity (see below).

Methods: Nexus and Induction

For our research, we will be utilizing a nexus and inductive approach; we will be drawing conclusions based on data and observations that we make in teenage films. Below we have six films, two from each of the three decades of our research parameter, that we believe will be illustrative of the teenage perception:

1980’s: The Breakfast Club, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off

1990’s: Clueless, 10 Things I Hate About You

2000’s: Mean Girls, The Princess Diaries

As we watch these films, we will be observing and taking notes of specific instances of derogatory language use by teenagers, as well as creativity and complexity levels. One way we have found to quantify these measures is to check if an insult actually contains an insult or a derogatory word, or whether it contains a series of words, reliant on references and word plays, constructed to make an insult. Additionally, we will analyze word choices in terms of commonality of use, with the thought in mind that less common words constitute a more creative insult. Once we have our data on creative versus non-creative insults, we will be able to form a ratio. We will compare the ratio between men and women in the movies, between the different decades, and between men and women differences in different decades. Further methods of analysis will include measurements of length, as well as comparisons of the types of references made across our parameters. As we have mentioned previously, we predict that insult use is more creative among women, and that insult use has become less creative since the 1980s.

Definitions / Parameters

Complexity: a function of length, diction, syntax.

Length: number of words in an insult or an insult group

Diction: word choice (common/uncommon)

Syntax: construction; whether the insult is formed in a non-declarative, complex way

Creativity: a measure of tone, reference, and blatant insult word choice

Tone: insults delivered through the use of tone or body language

Reference: use of references that are contextually significant in making the meaning of an insult apparent. This can fall into two main categories:

Cultural: An appeal to cultural, epistemic domains, such as arts and history, that are predominantly apparent to the individuals.

Social: An appeal to social norms, an attempted outing of the individual from the social hierarchy from an identity perspective.

Presence of blatant insult word: whether one insults with a pre-established jab or creates the pointedness themselves.

Results: Correlations

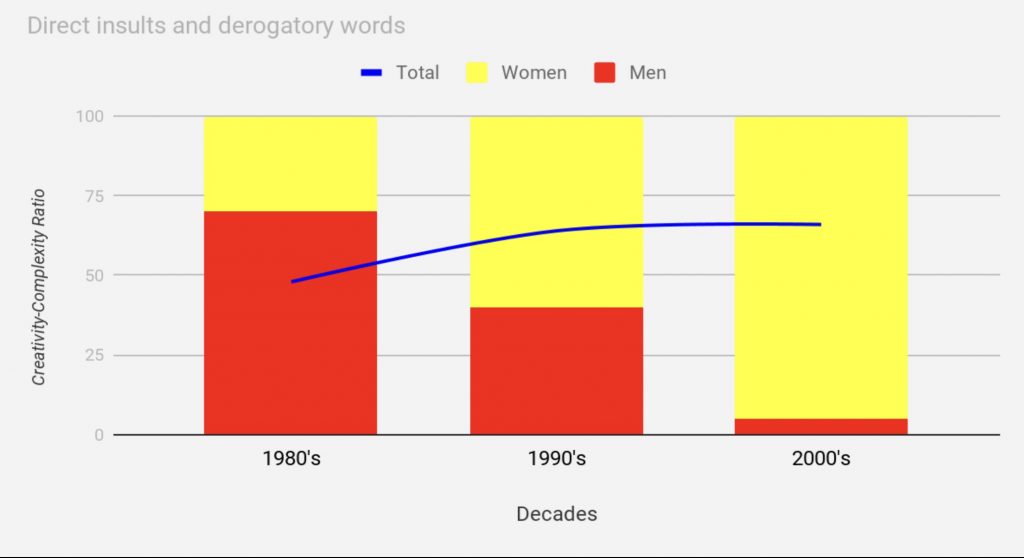

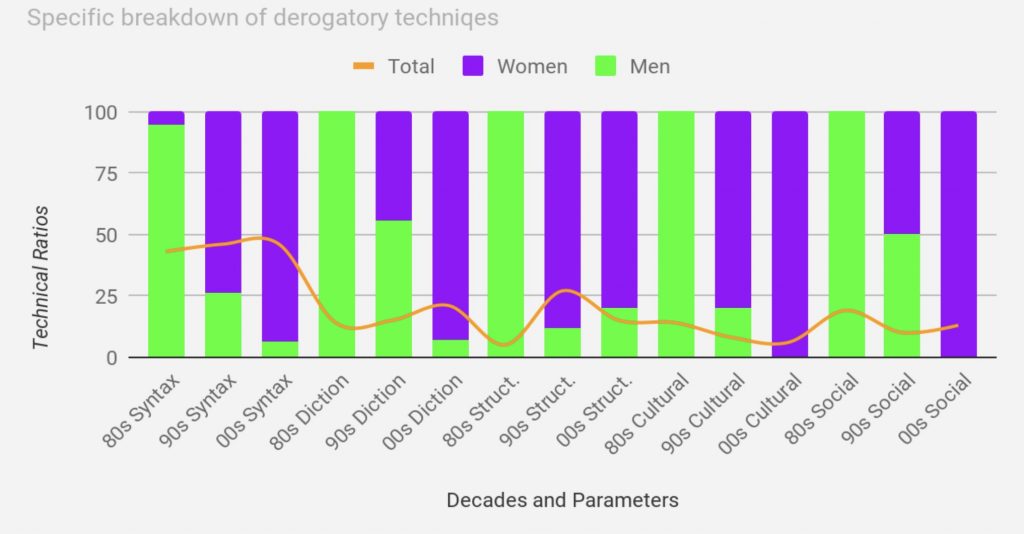

Our data from the 1980s is from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and The Breakfast Club. The combined data from the two films tells us that the average word length per female insult is 5.71, and for males is 12.54. 46% of the insults were syntactically significant, and only 5.6% of those which were syntactically significant were from females. Social and cultural references were 19% and 14%, respectively, with females contributing 0% to both categories. 14% of the insults included uncommon and notable lexicon, but again with 0% contribution from females. In 5% of the data we saw insults delivered through tone, all attributed to male insults.

Our data from the 1990s films Clueless and 10 Things I Hate About You were 64% female. The average word length for a female-given insult is 8.84 words, and for males it was 8.54 words. 46% of the insults given were syntactically significant, and 78% of these are attributed to females. Only 15% of insulted included uncommon word choice, and about 44% of these were given by women. In regards to references, females made up around 80% of all cultural referenced insults, 50% of socially referenced insults. 27% of the insults were delivered through the use of tone, and 88% of those were female-delivered.

Our data from the 2000s derives from Mean Girls and Princess Diaries. From these films, 94% of the insults were from females. The average female word length was 6.45, and the average male word length is 9. 46% of the total insults were syntactically significant, and 93% of those were from women. In regards to references, 6% of the insults included cultural references and 13% included social references; all of these are attributed to females. 21% of the insults contained uncommon word choice, 93% from females. In regards to insults delivered through tone, 15% of the total insults employed this method and 80% is due to females. Finally, 66% of the insults contained an actual insult word, with 95% of that being from females.

Our data from the 80s show us that males employed much more complex and creative insults than females at the time. Going into the 90s, the trend shifts, and the majority of our data point to women being a bit more creative and complex in their insult use than their male counterparts. Finally, in the 2000s, we see a drastic change in our results with women demonstrating much higher levels of insult creativity and complexity than men. We were off from our original predictions. We see from our data that insults, among females, increased in complexity and creativity. Additionally, we do not see a decrease in general creativity as we moved through the decades.

Discussion and conclusions: Why We Offend

First, from a pragmatic perspective, why do teenagers feel the need to beat around the bush in insults? At first glance it seems rather counterintuitive, but as we have seen, they serve important linguistic functions. For one, creative and complex insults can inflict a greater amount of damage by constructing a vehicle in which the insult can be delivered in more deceptive and cognitively disorienting way. It can also be viewed as a “flex” of intellectual superiority, or as a way to make the insult less refutable, as a retort would necessitate an equal level of craftsmanship (Goffman, 1971).

But why do we insult? What do we have to gain in insulting others? From our observations, it appears to be a practice of identity projection, of a more aggressive degree, because it is forceful definition of the self via an equally forceful definition of the other. In other words, along the same line of “who am I if not myself?,” it appears that the teenage response is merely “I am not you.” This seems to suggest that identity is only salient, or more radically, only existent, through expression and a process of negotiation and prioritization with the other. Insults serve as a way to categorize and define oneself against others (Marsden, 2009).

References

Brinkley, A., & McGraw-Hill Education (Firm). (2013). American history : Connecting with the past (Twelve edition, Updated. Updated AP ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education.

Dijk, C. V. (2016). The Influence of Texting Language on Grammar and Executive Functions in Primary School Children. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4816572/

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public: Microstudies of the public order. New York: Basic Books.

Kalinak, K. M. (2010). Film music a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, USA.

Marsden, E. (2009). What the Fuck? An Analysis of Swearing in Casual Conversation. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/3871040/What_the_Fuck_An_Analysis_of_Swearing_in_Casual_Conversation

Mooney & Evans (2015) Language and Gender. In Language, Society and Power (pp. 108-131). London: Routledge.