Grace Gibbons, Maya Kardouh, Orla Lynagh-Shannon, Diya Razdan

Does one’s gender affect the language features that he or she uses? Previous studies, specifically by Robin Lakoff, a prominent linguist, have shown that women’s language differs from men’s in that women are expected to “talk like a lady” and consequently use more hedges, intensifiers, tag questions, and adverbs in their language (Lakoff, 1975). Lakoff argued that this difference in language features reflects uncertainty, less assertiveness, and unequal power in women as compared to men. Another study done by Hanafiyeh and Afghari refuted such argument where the hypothesis was rejected in their data (Afghari and Hanafiyeh, 2014).

Such contradiction motivated us to conduct our own study by investigating the same question, however, the setting would be specific, workplace settings, and the language scripted. We did that by selecting male and female boss characters from 2000s movies and TV shows. We compared if there is a difference between the number of modifiers used by male vs. female characters.

Although the language used by the characters is scripted, it still reflects how the two genders are intended to be viewed and the reality that they are intended to mimic. The specific language feature we investigated was modifiers per adjective, which can be divided into qualifiers and intensifiers. Our selected movies were The Proposal, Horrible Bosses, The Devil and Wears Prada, and TV shows were The Office and Parks and Recreation.

Modifiers consist of qualifiers, which are words or phrases that precede an adjective or an adverb to weaken or minimize it, as well as intensifiers, which are words or phrases that emphasize and strengthen adjectives and adverbs. In order to see if the use of modifiers is related to gender in the workplace, we compared the number of times qualifiers and intensifiers are used by female boss characters vs. male boss characters when speaking to an employee in an office setting. Our hypothesis was that there is a significant difference between the number of times that modifiers are used between female and male boss characters since the heightened use of modifiers is already linguistically associated with females. Not only is the use of modifiers associated with females, but it is also associated with passiveness. Inversely, the decreased use of modifier words is an indicator of assertiveness, which is tied to males. When we investigated how the media portrays assertiveness in males versus females in positions of power, we expected to see these associations to be reflected in the scripts, in which women are portrayed as less assertive even when it is logical for them to be so in their character’s position.

We chose to study this particular topic because gender inequity, now more than ever, is an increasingly relevant topic. In the context of the workplace, boss and subordinate roles add an extra layer of power interplay that affects the identities males and females adopt. For example, most organizations have males occupying senior level positions. Furthermore, women tend to avoid assertiveness and positions of visibility in order to “avoid conflict” (Sing, Magliozzi, Ballakrishnen, 2018). Across the board, women in the workplace therefore tend to find themselves in positions of submissiveness and passivity. We predicted that this would transfer over to language use by way of use of modifiers, which are typically seen as less assertive. With this in mind, our target population was aimed at men and women in positions of authority, as they are portrayed in film and television.

Linguistically, we focused on qualifiers and intensifiers and what their usage indicates about the speaker. A modifier’s function is to increase or decrease the quality signified by the word it modifies. Furthermore, we used Lakoff’s description of women’s language as hyper-polite and non-assertive as opposed to men’s language being more assertive as a base for our expectations of the two genders’ language in workplace environments. We set out with the belief that females are more inclined to use both qualifiers and intensifiers, which are seen as more passive than assertive. In contrast, we expected more of the men in film and television to use fewer qualifiers and intensifiers to come off more assertive and direct.

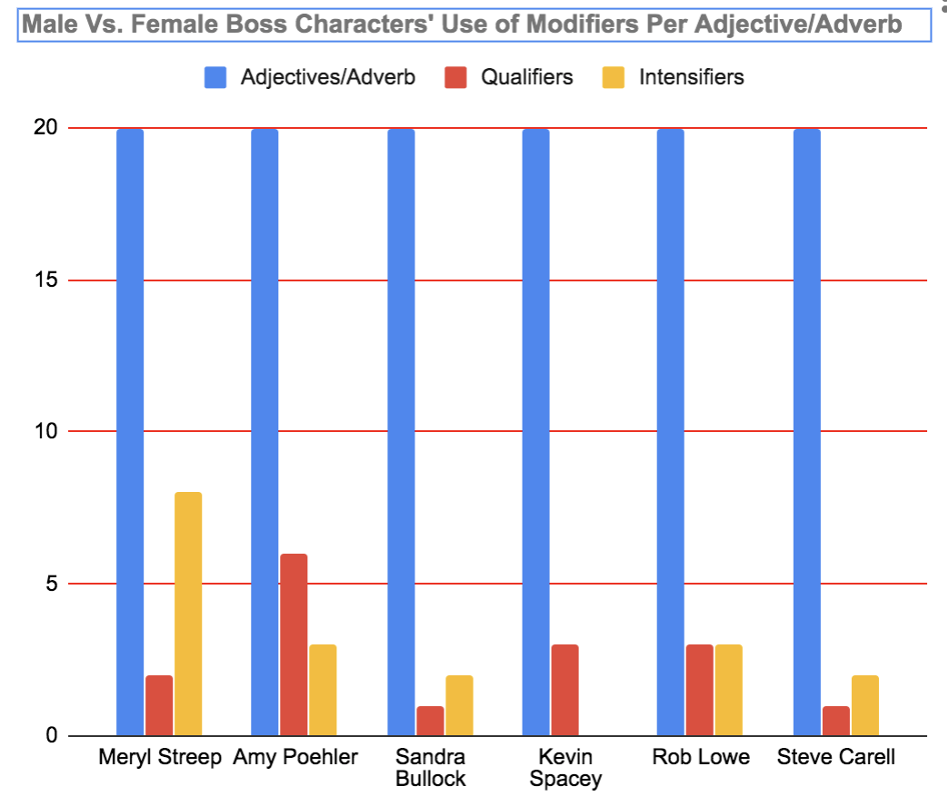

We selected scenes from movies and TV shows made in the 2000s that involve interactions between a female boss character with her employee(s) or a male boss character with his employee(s). The sample number was three female and three male boss characters. We analyzed enough scenes to count 20 adjectives and adverbs per character. Then, we counted intensifiers and qualifiers used per adjective/adverbs.

We defined modifier words as intensifiers and qualifiers, specifically, we adopted the Towson University definition “qualifiers are function parts of speech. They do not add inflectional morphemes, and they do not have synonyms. Their sole purpose is to “qualify” or “intensify” an adjective or an adverb.” Qualifiers include words as “kind of”, “barely”, “possibly”, “probably”, “sort of”, “slightly”, and “somewhat.” Intensifiers include words such as “rather”, “absolutely”, “totally”, “really”, “utterly”, “completely”, “very”, “quite”, and “extremely.”

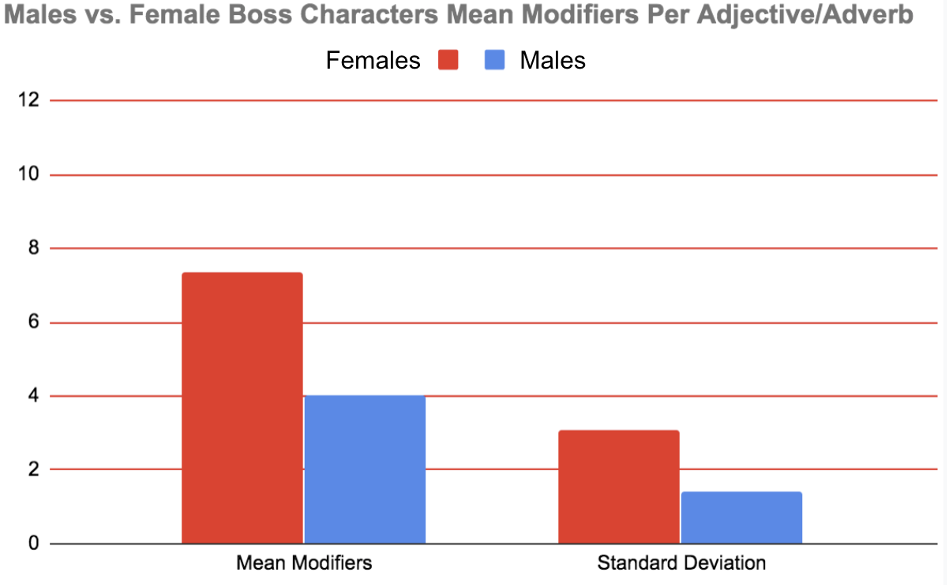

Adding the numbers of qualifiers and intensifiers and dividing them by 20 adjectives/adverbs, we found the numbers of total modifiers per adjective/adverb used. Calculating the average and standard deviations for the total modifiers per adjective/adverb for the male and female groups, we used the statistical significance test to evaluate if there indeed is a significant difference in this language feature between males and females as proposed by Lakoff.

We observed a greater average of modifiers per adjective/adverb in the female boss characters group as compared to the male boss characters group. The female group also had greater standard deviations well. All women tended to use both qualifiers and intensifiers. Specific characters such as Meryl Streep in The Devil Wears Prada used more intensifiers than qualifiers, conversely Kevin Spacey in Horrible Bosses used very few qualifiers and no intensifiers at all. No trend was seen in qualifiers or intensifiers use alone. Although females on average used more modifiers than males, the difference was not significant according to the statistical significance test.

Analyzing our data, we found that there was no statistical significance in the number of modifiers used by females in comparison to male characters. Though there was a slight tendency for female boss characters to use more modifiers on average, there was not enough of a difference for the results to be deemed significant. This being said, some choices in the way we conducted our study may have impacted these results – as such, our results do not necessarily reflect how male and female language use differs in real life. For one thing, most of the shows we analyzed were comedies. The fabricated nature and humorous intent behind many of the scenes we observed may have led them to be less authentic representations of genuine language use.

Furthermore, the number and types of scenes we looked at may also have skewed the data — using a larger sample size may have reduced the effect of outliers and randomizing the scenes we chose may have produced more accurate results. Therefore, while our experiment in particular did not show any statistically significant difference in modifier use, it is possible that different contexts or circumstances may yield more stratified results.

While we see that our hypothesis was not supported, there are multiple possible explanations for the observed results. We originally believed that stereotypes of the sexes would persist in these portrayals of male and female bosses, but the difference in the amount of modifiers used between the sexes was not nearly significant enough to support this idea. We now realize that since holding positions of power is already associated with masculinity, this could potentially explain why the female bosses overall were very similar to the male bosses in their use of modifiers. Because the language of both the observed male and female characters follow similar speaking patterns, this could explain how these women fit the “boss” role as men started working before women and their language became associated with the work positions they occupied. We believe that this conclusion is very important, since it shows how in this data sample females who achieve positions of power generally take on linguistic styles more related to males, which further perpetuates the idea that men are more fit for positions of power.

As we previously mentioned, gender inequity is an increasingly relevant topic. And because all of us behind this study identify as women, we hope ourselves to not be victims of gender inequity in our own careers. Thankfully, studies like these will continue to investigate, highlight, and hopefully change this inequity in all aspects of life, not just in the workplace.

For further information on the comparison of men and women’s speech patterns in the workplace, we recommend listening to “Deborah Tannen on Talking from 9 to 5 – The John Adams Institute.” This talk was given by the linguistics professor at Georgetown University who specializes in the role of speakers’ gender in language. Tannen sheds light on how women and men in the workplace differ in how they ask for information, delegate, and make decisions.

References:

Ballakrishnen, S., Fielding-Singh, P., & Magliozzi, D. (2019). Intentional Invisibility: Professional Women and the Navigation of Workplace Constraints. Sociological Perspectives, 62(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0731121418782185

Crosby, F., & Nyquist, L. (1977). The female register: An empirical study of Lakoff’s hypotheses. Language in Society, 6(3), 313-322. doi:10.1017/S0047404500005030

Deborah Tannen on Talking from 9 to 5—The John Adams Institute. (1995). Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UCMmTmD-OJI

Fahy, P.J. (2002). Use of Linguistic Qualifiers and Intensifiers in a Computer Conference. Hanafiyeh, M., & Afghari, A. (2014). GENDER DIFFERENCES IN THE USE OF HEDGES,TAG QUESTIONS, INTENSIFIERS, EMPTY ADJECTIVES, AND ADVERBS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY IN THE SPEECH OF MEN AND WOMEN.

Lakoff, R. (1973). Language and Woman’s Place. Language in Society, 2(1), 45-80. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/4166707

Park, G., Yaden, D. B., Schwartz, H. A., Kern, M. L., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kosinski, M., Seligman, M. E. (2016). Women are Warmer but No Less Assertive than Men: Gender and Language on Facebook. PloS one, 11(5), e0155885. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0155885

QUALIFIERS / INTENSIFIERS – words like very, too, so, quite, rather. (2019). Retrieved November 13, 2019, from Towson.edu website: https://webapps.towson.edu/ows/qualifiers.htm

Why Women Stay Out of the Spotlight at Work. (2018, August 28). Retrieved November 13, 2019, from Harvard Business Review website: https://hbr.org/2018/08/sgc-8-28-why-women-stay-out-of-the-spotlight-at-work