Asfa Khan and Ayub Abdul-Cader

A world where words wield power and every hashtag tells a story—welcome to the exploration of slang on Twitter.

Exploring the intricate dance between language, identity, and culture, this study delves into the phenomenon of linguistic appropriation on Twitter. Focusing on the adoption of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) by non-Black individuals, particularly white working-class Twitter users, we uncover patterns that illuminate the dynamics of identity formation in digital spaces. Through analysis of tweets from Black Drag Queens and white Twitter users, we dissect linguistic elements such as phonetics, word choice, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Our findings reveal a nuanced picture of language use, shedding light on the motivations behind linguistic appropriation and its implications for cultural dynamics and societal norms.

[expander_maker id=”1″ more=”Read more” less=”Read less”]

Introduction

African American Vernacular English (AAVE): The Dialect We Call Our Own – Because of Them We Can

In today’s digital age, social media platforms like Twitter serve as microcosms of linguistic diversity, offering insights into how language is used and appropriated across different communities. Our study zooms in on the use of slang, particularly AAVE, among Black Drag Queens and white working-class Twitter users. The origin of these slangs has been falsified for many years, as many in the linguistic community believed working-class men were the main group who created/implemented AAVE. As seen by the UMASS research group, “early work on AAE perpetuated myths that the language variety was uniform across regions and that it was spoken primarily by working-class men, due to being conducted in inner city areas and examining a specific set of linguistic features” (Masis 2023). These myths have only further fueled the fire that is cultural appropriation, specifically in regards to AAVE slang which are primarily used and created by the Black Drag Queen Community. By examining linguistic patterns, we aim to address the appropriation and misuse of AAVE by non-Black individuals, highlighting its impact on cultural dynamics and identity formation. This research builds upon existing literature in linguistic anthropology, which underscores the need to recognize and honor the origins of linguistic expressions while promoting mindfulness regarding their impact on marginalized communities.

Methods

Methods

We employed two primary methods for data collection: identifying key accounts and leveraging hashtags and trends related to drag culture and AAVE. By focusing on tweets from Black Drag Queens and white Twitter users, we analyzed linguistic elements such as phonetics, word choice, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics. Our analysis aimed to uncover patterns of linguistic appropriation and identity formation within digital environments.

Results

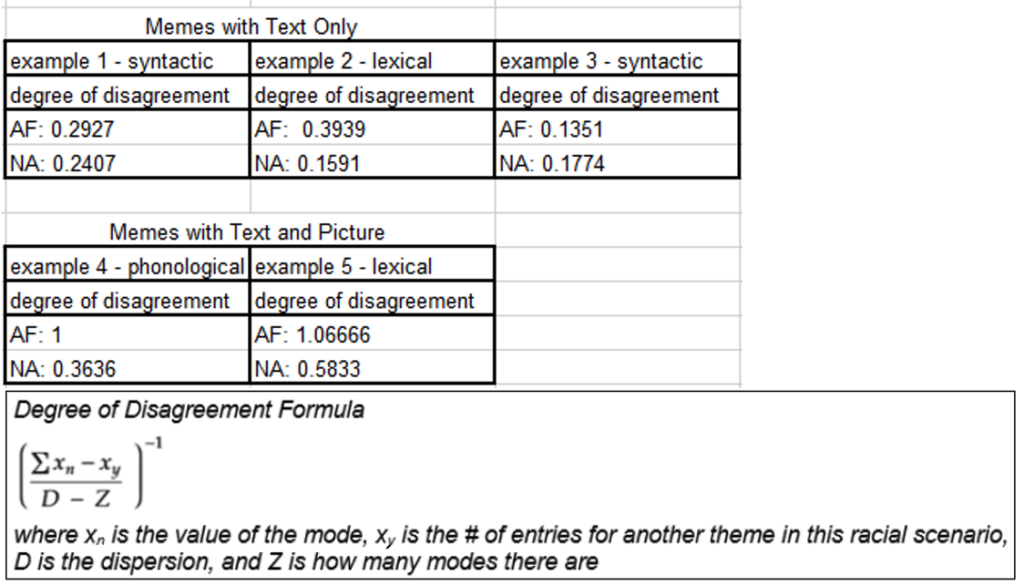

Our analysis revealed a discernible trend wherein white Twitter users demonstrate a propensity to adopt and replicate the linguistic style characteristic of Black Drag Queen Twitter users. Analyzing Tweets by white, middle-class men and Black Drag Queens helped us understand the misuses of AAVE efficiently. A white man used the words “Yo this is bussin” in a tweet and a famous phrase that originates in African communities non-individuals from communities using AAVE is cultural appropriation. Linguistic analysis allows us to understand when words are being used as cultural appropriation.

Discussion

While Black Drag Queens employ AAVE as an intrinsic component of their everyday discourse, white users often utilize it as a means to cultivate an alternative dimension of their identity primarily manifesting within the online realm of Twitter. Examples such as the use of “ass” as a postpositive particle and the alteration of “with” to “wit” exemplify this linguistic appropriation.

Bob the Drag Queen Teaches You Drag Slang | Vanity Fair

Our findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between language, identity, and culture in digital spaces. By uncovering patterns of linguistic appropriation, we shed light on the motivations behind the adoption of AAVE by non-Black individuals and its implications for cultural dynamics. This research underscores the need for individuals to be mindful of the impact of their language on marginalized communities and to respect cultural heritage and contributions. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of recognizing and honoring the origins of linguistic expressions while promoting inclusive and respectful communication practices.

This study draws inspiration from literature in linguistic anthropology, which emphasizes the role of language in shaping cultural dynamics and identity formation. Scholars have long discussed the appropriation and misuse of AAVE by non-Black individuals, highlighting its perpetuation of harmful stereotypes and inequalities. According to the UMASS research group, led by Tessa Masis, “Our results show that, contrary to sociolinguistic myths of uniformity, there is clear variation in AAE across both geographic and social dimensions (Masis 2023).”

By building upon this literature, our research offers a nuanced analysis of linguistic appropriation on Twitter, providing insights into the motivations and implications of language use in digital environments. In the ever-evolving landscape of digital communication, the exploration of slang on Twitter serves as a window into the complexities of language, identity, and culture. Through our research, we invite readers to delve deeper into the nuances of linguistic appropriation, fostering a deeper understanding of the power dynamics at play in online discourse. As we navigate the digital labyrinth of Twitter, let us remain vigilant in our pursuit of inclusive and respectful communication practices, honoring the rich tapestry of linguistic diversity that defines our digital landscape.

Conclusion

In the dynamic world of digital communication, where language shapes identities and cultures, our study serves as a springboard for future research endeavors exploring linguistic appropriation and digital discourse. Our research methodology lays a sturdy groundwork for data collection and analysis. By integrating the identification of key accounts with the exploration of relevant hashtags and trends, researchers can cast a wide net to gather a diverse dataset reflecting various linguistic communities on Twitter. Our focus on analyzing linguistic elements such as phonetics, word choice, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics offers researchers a multifaceted lens through which to examine patterns of linguistic appropriation. Potential analysis tools such as the BERT machine learning tool, used by the UMASS research group in order to narrow down research methods. These methods provide a more efficient way of analyzing tweets in specific, due to there being hundreds of millions of tweets throughout the history of the social media app. “Many feature-based studies of large corpora use keyword searches or regular expressions to detect features; however, keyword searches are limited by orthographic variation in tweets and regular expressions cannot be made for all features. To circumvent these obstacles, we use the BERT-based machine learning method used in Masis et al” (Masis, 2023).

By employing similar analytical techniques, researchers can uncover subtle nuances in language use and identity formation within digital environments. This approach fosters a deeper understanding of the intricate interplay between language, culture, and identity in online spaces. Researchers can expand on this theme by exploring the implications of linguistic appropriation for marginalized communities and investigating strategies for promoting respectful and equitable language use in online spaces.

References

Ilbury, C. (2019). “Sassy Queens”: Stylistic orthographic variation in Twitter and the enregisterment of AAVE. Journal of Sociolinguistics. 24. 10.1111/josl.12366.

Magazine, Smithsonian. “The First Self-Proclaimed Drag Queen Was a Formerly Enslaved Man.” Smithsonian.Com, Smithsonian Institution, 9 June 2023, www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-first-self-proclaimed-drag-queen-was-a-formerly-enslaved-man-180982311/.

Masis, Tessa; Eggleston, Chloe; Green, Lisa J.; Jones, Taylor; Armstrong, Meghan; and O’Connor, Brendan (2023) “Investigating Morphosyntactic Variation in African American English on Twitter,” Proceedings of the Society for Computation in Linguistics: Vol. 6, Article 41.DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/zdg0-0914

[/expander_maker]